Black Diamonds (63 page)

Authors: Catherine Bailey

Tags: #History, #England/Great Britain, #Nonfiction, #Royalty, #Politics & Government, #18th Century, #19th Century, #20th Century

‘No, it was not mentioned and we never talked about it.’

Toby’s lawyers reasoned that George and Evie had every reason to keep their wedding secret. In the 1880s it was regarded as a disgraceful and shocking thing for a young man of good family to marry an actress. In the Guards regiments, the rules were plain. If an officer married an actress, he had to resign his commission.

But why then a second wedding in London? George, in numerous statements to his solicitor, had claimed that he and Evie had married at Hanover Square because they were told the Scottish marriage was invalid. ‘

Your Lordship

ought to accept George’s own account,’ Toby’s barrister, Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, urged the judge, ‘that they were married in Scotland and somebody threw doubts on it … Your Lordship knows how wiseacres always haunt London clubs full of information of that kind, and in some way they accepted that and thought they should get married again.’

Unluckily for George, news of the Hanover Square wedding leaked out, forcing him to resign his commission in the Blues. The pew opener at St George’s, a Dickensian figure by the name of Sargeant and the only other witness to the marriage besides Kate Rickards and the Vicar, was the servant of an old Fitzwilliam retainer. Via Sargeant, word reached the senior branch of the family. It was the 6th Earl’s view of the alleged wedding in Scotland and his reaction to Toby’s birth that finally enabled the judge to decide the case.

William, Earl Fitzwilliam, who was George’s uncle, and who had been appointed guardian to George and his two sisters after the death of their father, was firmly convinced that Toby was illegitimate. It was not until two and a half years after Toby was born that George’s guardian heard of the baby’s existence. Writing to George in the winter of 1891, the Earl expressed his grave displeasure:

I have just heard that you propose taking a little boy to Milton. I know nothing about the poor little fellow, but I should not be doing right if I did not point out to you the disastrous effects of taking him there. The evil effects of such an example would be very great, and would mar your future influence for good in the neighbourhood, and later on the consequences would fall very heavily on both you and your sisters. If you take that little boy to Milton, you permanently close the door to your sisters, whether they were actually there at the moment or not. Your sisters suffer now, and must continue to suffer, much on your account; do not add to it more than you can help.

The 6th Earl’s letters to his nephew were among the very few contemporaneous pieces of evidence. ‘

It is perfectly

clear, indeed it is not in dispute,’ Mr Justice Pilcher told the court in his Judgment, given on the twentieth day of the hearing, ‘that the opinion which the Sixth Earl formed when he first heard of Toby’s existence, namely that he was illegitimate, never altered until the date of his death in 1902.’

Mr Justice Pilcher ruled against Toby. Tom’s side had convinced him that the Scottish wedding had never taken place. George and Evie had lied: their claims to have been married in Scotland, both in their conversations with friends and with members of the family and in the various sworn declarations and statements made to their lawyers, were a ‘put-up job’, a ‘stage performance’, ‘a bluff’ by ‘theatrical people’ who were ‘theatrically-minded’. In the damning words of Tom’s barrister, ‘They knew full well that there had never been any ceremony in Scotland and that these remarks were made to keep up appearances knowing that they were always and had been untrue.’

Evie Fitzwilliam, the judge concluded, could not possibly have destroyed the papers proving Toby’s legitimacy: none had ever existed for her to destroy.

Toby never commented on the outcome of the case. But there was at least some consolation. Throughout his life, his predicament had struck a chord with his cousin Billy, the 7th Earl Fitzwilliam. It is possible the question mark over Toby’s legitimacy reminded Billy of his own troubles in the 1890s when the family had accused him of being an impostor. In the early 1930s, he made an unusual provision in his will: should the younger brother, Tom Fitzwilliam, ever succeed to the Earldom, he stipulated that Toby should receive an annual allowance of £8,000 from his estate. It was an act of remarkable generosity on Billy’s part. An income of £8,000 a year was more than enough to live on comfortably: in the early 1950s, it was equivalent to almost £170,000 today.

The dry, precise language of Mr Justice Pilcher’s sixty-page Judgment failed to conceal the family’s torrid unravelling. In just five decades, the dynasty had been destroyed by love.

In 1956, four years after he had become the 10th Earl Fitzwilliam, Tom finally married Joyce Fitzalan-Howard, the older woman he had loved for almost half his life and by whom, ironically, in the mid-1930s, he had had an illegitimate daughter. The marriage embroiled the family in yet another scandal. In order to marry Tom, Joyce divorced Viscount Fitzalan of Derwent, her husband of thirty-three years’ standing and the heir to the Duke of Norfolk, the head of England’s premier Catholic family. Tom and Joyce’s marriage signalled the end of the Fitzwilliam line: in 1956, Joyce, aged fifty-eight, was too old to produce an heir.

Tom lived until 1979. Although he retained the suite of forty rooms at Wentworth House, he chose to live at Milton Hall, visiting Wentworth for just three weeks in every year for the grouse-shooting season and the St Leger at Doncaster. A few months before he died, his final act as the 10th and last Earl Fitzwilliam – one commensurate with his predecessors’ philanthropy – was to transfer the village of Wentworth into a charitable trust. The future rents from the hundreds of properties were to be ploughed back to improve its amenities and to maintain the standard of housing.

The local authority gave up their lease on Wentworth House in the mid-1980s. After the Lady Mabel College of Physical Education closed in 1979, Sheffield City Polytechnic took over the historic property. But the annual maintenance costs, running into hundreds of thousands of pounds, were prohibitive: the heating bill alone was £1,000 a week.

For the second time in its twentieth-century history, Wentworth House was unmistakably a white elephant. The extraordinary size of it, and its location in what was now one of the most depressed regions in Britain, prevented it from being put to institutional use. It had been built for show, for one purpose only: to be one powerful man’s stately home. After the years of occupation by the local authority, Tom Fitzwilliam’s trustees balked at the expense of putting it right. In 1988, Lady Elizabeth Anne Hastings, Tom’s daughter and beneficiary, put the house up for sale. It had been in the family’s possession for more than 250 years. Before that, their ancestors had first built a house on the site in the thirteenth century.

In a twist of historical coincidence, 1988 was also the year that many of the pits in the South Yorkshire coalfield closed down, the culmination of a bitter and bloody clash between the country’s miners and Margaret Thatcher’s Government. The dispute which precipitated the year-long miners’ strike of 1984/5 had begun at Cortonwood colliery, a pit situated on land formerly owned by the Fitzwilliams a few hundred yards from Lion’s Lodge, the most northerly of the eight gatehouses that led into Wentworth Park.

In 1989, the house and some thirty acres surrounding it was bought by Wensley Haydon-Baillie. His tenure was short. A flamboyant businessman, the son of a surgeon, he already owned a large country house in the New Forest, and a mansion next to Kensington Palace in London’s ‘Millionaires’ Row’. After making his fortune in banking and engineering, Haydon-Baillie invested in a company called Porton International, founded in the mid-1980s to market drugs developed at the Government’s classified biochemical research station at Porton Down. At one point, the company, launched on the promise that it would soon be introducing a cure for the disease herpes, was valued at around £400 million. It failed to live up to City expectations. While it supplied anti-germ-warfare vaccines to US troops in the first Gulf War, the cure for herpes never materialized. By the summer of 1998, Haydon-Baillie admitted to having debts of £16 million. Shortly after, Wentworth House was repossessed by his bankers.

After standing empty for a year, its lawns neglected and the roof in danger of collapse, it was bought by an anonymous bidder for the knockdown price of £1.5 million – cheaper per square yard than a council house in the nearby town of Rotherham.

The mystery that shrouds the twentieth-century history of Wentworth House continues. It is currently owned by Clifford Newbold, a former Londoner in his early seventies, and a reclusive figure about whom little is known. He remains aloof from the village, determined to guard his privacy and to shield Wentworth House from the inquisitive eyes of visitors drawn to its grounds. ‘

Its closure

to the public is a crying shame,’ Simon Jenkins wrote in his book

England’s Thousand Best Houses

. His view is echoed in the village, where memories of the Fitzwilliams die hard. ‘It should be our Chatsworth, our Blenheim,’ one man in his eighties remarked.

Today, as a consequence of the 10th Earl Fitzwilliam’s legacy, Wentworth village looks much as it would have looked in the family’s heyday. It is one of the most timelessly beautiful communities in South Yorkshire. Untarnished by development, the yellow stone cottages, with their green-painted guttering and doors, and white window frames, still bear the Fitzwilliam colours. Yet fittingly for a family whose reticence has veiled their recent history, the true magnificence of the last Earl’s legacy can only be seen after dark.

Along the top road north of the village, a narrow country lane leads to Hoober Stand, a pyramid-shaped folly erected by the Fitzwilliams’ ancestor, the 1st Marquess of Rockingham, to commemorate the English victory over the Scots at the Battle of Culloden. At night, the view over the surrounding country stretches for miles. To the south, the hills above Sheffield are coloured by a livid orange glare; to the south-west, Rotherham and Rawmarsh blaze, a sodium-lit sprawl; the M1 marches along its western edge. But like totality in a solar eclipse, in the midst of this, one of England’s greatest urban conurbations, there is a vast expanse of black. Startling in its size and density, it conceals woodland, fields and parkland. It is the land once encompassed by the nine-mile perimeter wall that encircled Wentworth House.

1. Billy, 7th Earl Fitzwilliam, on a training exercise with the Wentworth Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, 1911

2. Troops guarding Wentworth House during the coal riots of 1893

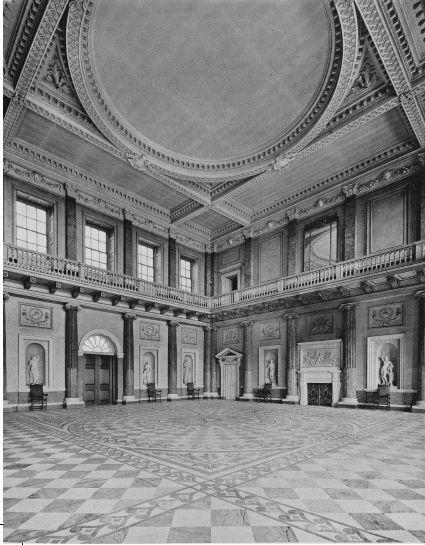

3. The Marble Salon at Wentworth House, 1924