Black Fire (35 page)

Authors: Robert Graysmith

Steam baths had been a fixture in the area long before the Gold Rush. Two blocks away, on the southwest corner of Montgomery and Sacramento streets, an Indian sweat house had once stood. The

temascal

, a combination hot-air bath and place of spiritual purification, was merely a six-foot-deep hole in the ground tightly covered with brush. A hole in the center allowed smoke to exit from the fire within. A narrow stream, now gone, coursed east down Sacramento Street to form a small freshwater pool known as Laguna Dulce (Sweet Water). After a half hour of steaming, the Native Americans, dripping with sweat, plunged into this chilly slough and emerged physically refreshed and spiritually revived, the same way the sauna affected Twain.

He and reporter Clement T. Rice, affectionately dubbed “the Unreliable” during their mock reportorial feud, were living high in a prestigious new tour-story hotel on Montgomery, at Bush, and had grown accustomed to dining on salmon and cold fowl. “I live at the Occidental House,” he bragged, “and that is Heaven on the half-shell.… In a word, I kept the due state of a man worth a hundred thousand dollars.” Sawyer envied him. He lived frugally while saving to buy a saloon on Mission Street. He and Twain discussed steamboats that they had in common. On February 28, 1857, Twain departed from Cincinnati for New Orleans as a passenger aboard the steamboat

Paul Jones

. “One of the pilots,” he recalled, “was Horace Bixby. Little by little I got acquainted with him and pretty soon I was doing a lot of steering for him in his daylight watches.” Twain got his pilot’s license in September 1859 and worked the Mississippi until April 1861, when the Civil War disrupted river traffic

and the Confederates purposely sank the first steamboat he ever piloted as a blockade at Big Black River. Piloting was the realization of one of Twain’s two powerful ambitions in life. His unrealized goal was to be a minister of the Gospel. Unfortunately, he lacked the necessary stock-in-trade: religion. He found it remarkable that his older, luckless brother, Orion (accent on the

O

), unmistakably heard the voice of God thundering in his ears yet aspired to be a lawyer. “It is human nature,” Twain said, “to yearn to be what we were never intended for.”

“He was about twenty years old when he went on the Mississippi as a pilot,” Twain’s invalid mother recalled. “I gave up on him then, for I always thought steamboating was a wicked business, and was sure he would meet some bad associates.” When he was a cub in the pilothouse of the

Aleck Scott

, freighting cotton from Memphis to New Orleans, the first engineer had gotten even with Twain (then Sam Clemens) for his practical jokes. “After working Sam to a nervous state about fire,” the engineer recalled with glee, “I waited until he was alone in the pilothouse and then set fire to a little wad of cotton, stuffed it into the speaking tube [running from the engine room to the pilothouse] and the smell came out right under his nose … hair on end, his face like a corpse’s, and his eyes sticking out so far you could have knocked them off with a stick, he danced around the pilothouse … pulled every bell, turned the boat’s nose for the bank and yelled, ‘FIRE!’ ”

As Twain heard Sawyer’s story of saving the passengers on the burning steamer

Independence

, in which hundreds were scalded to death by steam, his eyes grew wide. He had a deathly fear of exploding steamers and felt responsible for his brother’s death aboard one. His mother had asked him to kneel and swear on the Bible that he would look out for his slender, bookish, and frail younger brother, Henry. He had agreed.

In early 1858, he had a nightmare in which he saw his brother Henry’s corpse in a metal coffin resting on two chairs in his sister’s sitting room. A bouquet of white flowers, a single red rose in the center, lay on his chest. “In the morning when I awoke,” he wrote, “I had been dreaming, and the dream was so vivid, so like reality, that it deceived me, and I thought it

was

real.” Convinced Henry was dead, he walked one-half block up Locust Street toward Fourteenth when he realized it had only been a nightmare. He ran back and rushed into the sitting room. “And I was made glad again,” he said, “for there was no casket there.” A few weeks later Henry did die, in a boiler explosion onboard a steamer. Twain

had gotten Henry the job that killed him, an unpaid post on the New Orleans and St. Louis steam packet

Pennsylvania

. “He obtained for his brother Henry a place on the same boat as clerk,” his mother said, her voice trembling and eyes filling with tears, “and soon after Sam left the river Henry was blown up with the boat by an explosion and killed.” On the steamer Henry served as a mud clerk, a junior purser who checked freight at landings and often returned aboard from the riverbank with muddy feet. Twain’s own job as second clerk was to watch the freight piles from 7:00

P.M.

until 7:00

A.M.

for three nights every thirty-five days. Henry always joined his brother’s watch at 9:00

P.M.

to walk his rounds with him and chat for hours. Their first voyage together was uneventful until Tom Brown, the

Pennsylvania

’s pilot, unjustly tried to strike Henry with a ten-pound lump of coal. Twain let go the wheel, picked up a heavy stool, and hit Brown “a good honest blow which stretched him out.” Captain John Klinefelter, mightily impressed, offered Twain Brown’s job, but he declined and decided to depart the steamer at New Orleans and leave Henry behind.

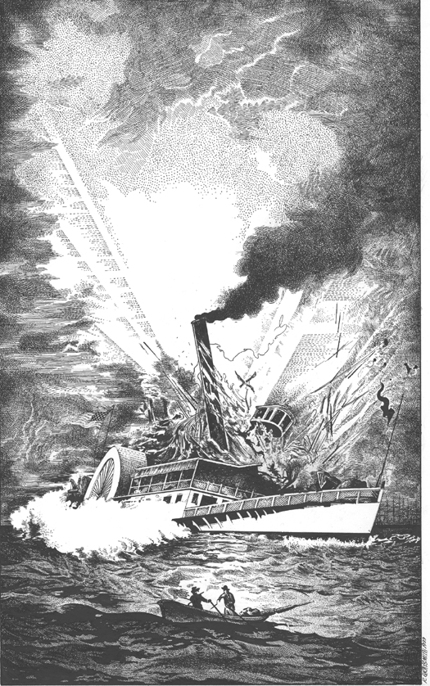

The night before he left, he sat with Henry on a freight pile on the levee and talked till midnight of steamboat disasters. “In case of disaster to the boat,” Twain advised, “don’t lose your head—leave that to the passengers.” He ordered Henry to rush for the hurricane deck and astern to the lifeboats lashed aft at the wheelhouse and obey the mate’s orders. “Thus, you will be useful,” he said, adding that the river is only a mile wide and he could swim that easily. At 6:00

A.M.

, June 13, a full week after Twain deserted the

Pennsylvania

, the steamer, under a half head of steam, exploded sixty miles below Memphis at the foot of Old Bordeaux Chute and four miles ahead of Ship Island. Four of the eight boilers blew up the forward third of the boat. Beefy Captain Klinefelter had been preparing to be shaved when the explosion left the barber’s chair with him in it overhanging a gaping chasm. “Everything forward of it, floor and all,” Twain recalled, “had disappeared.” The ship’s carpenter, asleep on his mattress, was hoisted into the sky by the blast and struck the water seventy-five feet away. Shrieks and groans filled the air. Many were burned to the bone or crippled. The detonation drove an iron crowbar though one man’s body. After the explosion, Brown, the pilot, and George Clark, the chief, were never seen again. Twain, following on the

A. T. Lacey

from Greenville, had the full story by the time he reached Memphis.

“Henry was asleep,” Twain said, “blown up—then fell back on the hot boilers.” A reporter wrote that Twain was “almost crazed with grief” at the sight of Henry’s burned form on a mattress surrounded by thirty-two parboiled and mangled victims on pallets. His head was shapelessly swathed in a wad of loose raw cotton. “His feelings so much overcame him, at the scalded and emaciated form before him, that he sank to the floor overpowered.” Henry had inhaled the lethal steam. His entire body was badly scalded, but he helped passengers evacuate before he lay on the riverbank under a burning sun for eight hours. Dr. Peyton, an old physician, took charge of Henry and at 11:00

P.M.

told Twain that Henry was out of danger. “On the evening of the sixth day, [Henry’s] wandering mind busied itself with matters far away and his nerveless fingers picked at his coverlet,” Twain recalled. Every day doctors removed the doomed to a partitioned chamber adjoining the recovery room so other patients might not be affected by seeing the dying moments. Twain watched the “death-room” fill with bodies as one victim after another succumbed. “[Henry] lingered in fearful agony seven days and a half during which time he had full possession of his senses … and then but for a few moments at a time. His brain was injured by the concussion, and from that moment his great intellect was a ruin.”

Dr. Peyton asked the young, barely trained doctors on watch to give Henry an eighth of a grain of morphine if he showed signs of being disturbed by the screams of the wounded. Because the neophyte physicians had no way to measure an eighth of a grain of morphine, they heaped a quantity on the tip of a knife blade and administered that to Henry. When one of his frenzies seized him, he tore off handfuls of cotton and exposed his cooked flesh. Three times Henry was covered and brought to the death-room and three times brought back to the recovery room. He died close to dawn. “His hour had struck; we bore him to the death-room, poor boy.… For forty-eight hours I labored at the bedside of my poor burned and bruised, but uncomplaining brother and then the star of my hope went out and left me in the gloom of despair.… O, God! This is hard to bear.” They placed Henry in an unpainted white pine coffin and Twain went away to a nearby house to sleep. In his absence, some Memphis ladies bought a metallic coffin for Henry, who had been a great favorite of theirs. When Twain returned to the death-room to pay his respects, he found his brother dressed in a suit of Twain’s clothing and laid out in a metallic coffin exactly as in his dream. All that was missing was the unique bouquet. “I recognized instantly that my dream of several weeks before was here exactly reproduced,

so far as these details went—and I think I missed one detail, but that one was immediately supplied, for just then an elderly lady entered the place with a large bouquet consisting mainly of white roses, and in the center of it was a red rose, and she laid it on his breast.” After Henry and 150 other human beings perished, Twain blamed himself and was still working the problem over in his mind by day and in vivid dreams at night. “My nightmares to this day,” he said, “take the form of my dead brother and of running down into an overshadowing bluff, with a steamboat—showing that my earliest dread made the strongest impression on me.” Twain left the steam baths determined to find a subject for his first novel that matched the rousing excitement of Sawyer’s real-life recounting of an exploding steamer. Always on the lookout for a young hero, he filed the story away. He had yet to hear of the six great fires that had destroyed San Francisco and to learn that Sawyer, too, was plagued by nightmares of exploding steamboats.

While in San Francisco, Twain tried to arrange employment as the Nevada correspondent for the

Daily Morning Call

. He picked up news wherever he could: the docks, the firehouse, the police station, the Bank Exchange cigar kiosk, and the Montgomery Street Turkish Baths. “Your deal, Sam,” Stahle said the next day. Neither Ed Stahle nor Sawyer called the red-haired journalist Twain. They called him Sam Clemens. “Mark Twain” was only one of dozens of playful pen names the writer had used since he was teenaged Samuel Langhorne Clemens. “W. Epaminondas Adrastus Perkins” was another. He had recently adopted his most famous sobriquet on the third of February and used it again on the fifth and the eighth in a letter from Carson City to the

Enterprise

while reporting legislative proceedings.

Twain

was river jargon for two fathoms (twelve feet) of water under the keel, the shallowest depth a steamboat could safely negotiate a river like the Mississippi. A half twain is fifteen feet. Captain Josiah Sellers, a masterful river pilot of greater navigational talent than the comparatively inept boatman Sam Clemens, supposedly had the nom de plume first while writing river news for the

New Orleans Daily Picayune

. He apparently thought nothing of appropriating Sellers’s name. “I laid violent hands upon [his signature] without asking permission of the prophet’s remains,” he drawled. “Captain Sellers did me the honor to profoundly detest me from that day forth.” With Sellers’s death a year earlier, the name was solely Twain’s. The truth was that Sellers had never used that pseudonym and Sam had perversely launched the self-deprecating myth himself.

His sojourn in San Francisco was profitable. “Ma,” he wrote, “I have got five twenty-dollar greenbacks—the first kind of money I ever had. I’ll send them to you—one at a time, so that if one or two get lost, it will not amount to anything.” Yes, these were rosy times. During his news-papering days in Nevada, he had gotten some free mining stocks as kickbacks for favorable mentions in the

Territorial Enterprise

. His Gould and Curry stock was soaring. He had bought fifty shares of Hale and Norcross silver stocks on margin that he still had not sold and the share price was now a thousand dollars. “I hesitated, calculated the chances, and then concluded not to sell. Stocks went on rising; speculation went mad; bankers, merchants, lawyers, doctors, mechanics, laborers, even the very washer women and servant girls were putting their earnings on silver stocks, and every sun that rose in the morning went down on paupers enriched and rich men beggared. What a gambling carnival it was! I’m close to selling and am anxious to embark upon a life of ease. My ambition is to become a millionaire in a day or two.”