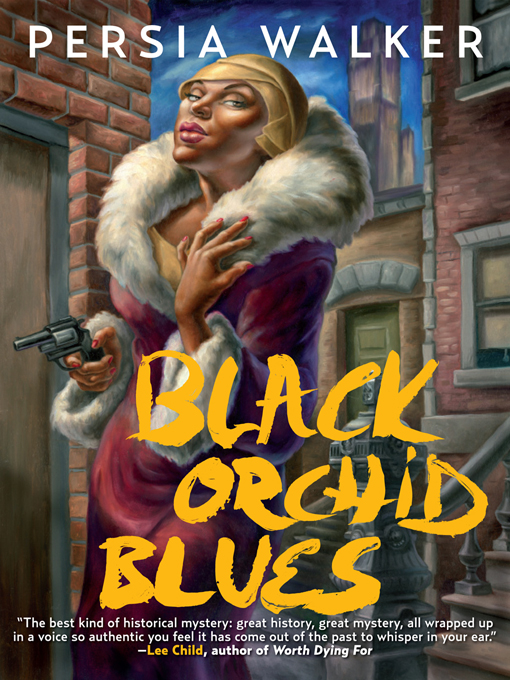

Black Orchid Blues

Read Black Orchid Blues Online

Authors: Persia Walker

This is a work of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Published by Akashic Books

©2011 Persia Walker

ePub ISBN-13: 978-1-617-75019-9

ISBN-13: 978-1-936070-90-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010939106

All rights reserved

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

I’d like to thank my agent Lukas Ortiz and Johnny Temple at Akashic for believing in this book. My thanks also go to Jerry Eisner, Catherine Maiorisi, Jane Aptaker, Sara J. Henry, and Elizabeth Zelvin for their patient rereads of the manuscript. Last, but not least, a word of gratitude to Shelton Walden for his constant encouragement.

Table of Contents

Q

ueenie Lovetree. What a name! What a performer! When she opened her mouth to sing, you closed yours to listen. You couldn’t help yourself. You knew you were going to end up with tears in your eyes. Whether they were tears of joy or tears of laughter, it didn’t matter. You just knew you were in for one hell of a ride.

Folks used to talk about her gravely voice, her bawdy banter, and how she could make up new, sexy lyrics on the spot. Queenie captured you. She got inside your mind, claimed her spot, and refused to give it up. Once you heard her sing a song, you’d always remember her performance. No matter who was singing it, Queenie’s voice would come to mind.

Sure, she was moody and volatile. And yes, whatever she was feeling, she made sure you were feeling too. But that was good. That’s what could’ve made her great—

could’ve

being the operative word.

I first met Queenie at a movie premiere at the Renaissance Ballroom, over on West 138th Street. The movie I’d soon forget—it was some ill-conceived melodrama—but Queenie I would always remember.

It was a cold day in early February, with patches of dirty ice on the ground and leaden skies overhead. It was late afternoon, an odd time for a premiere, so the event drew few fans and, except for Queenie, mostly B-level talent.

It was a party of gray pigeons and Queenie stood out like a peacock. For a moment, I wondered why she was even there. She was vivid. She was vibrant. And when she found out that I was Lanie Price,

the

Lanie Price, the society columnist, she went from frosty to friendly and started pestering me to see her perform.

“I’m at the Cinnamon Club. You must’ve heard of me.”

Well, I had, actually. Queenie’s name was on a lot of lips and I’d heard some interesting things about her. I could see for myself that she was bold and bodacious. I decided on the spot that I liked her, but I couldn’t resist having a little fun with her, so I shrugged and agreed that, yeah, I’d heard of … the Cinnamon Club.

Queenie caught the shift in emphasis and was none too pleased. She raised her chin like miffed royalty, pointed one coral-tipped fingernail at my nose, and, in her most regal voice, said, “You will appear.”

I smiled and said I’d think about it.

The fact was I had a full schedule. A lot of parties were going on those days, and it was my job to cover the best of them. However, I finally did find time to stop and see Queenie a couple of weeks later. I called in advance and Queenie said she’d make sure I had a good table, which she did. It was excellent, in fact, right up front.

To the cynic, the Cinnamon Club was little more than a speakeasy dressed up as a supper club, but it was one of Harlem’s most popular nightspots. It was on West 133rd Street, between Seventh and Lenox Avenues, what the white folks called “Jungle Alley.” That stretch was packed with clubs and given to violence. Only a few weeks earlier, two cops had gotten into a drunken brawl right outside the Cinnamon Club. One black, one white—they’d pulled out their pistols and shot each other.

That was the neighborhood.

As for the club itself, it was small but plush. The lighting was dim, the chairs cushioned, and the tables round and tiny and set for two. All in all, the Cinnamon Club seemed luxurious as well as intimate.

It was packed every night and most of the comers were high hats, folks from downtown who came uptown to shake it out. They liked the place because it was classy, smoky, and dark. For once, they could misbehave in the shadows and let someone else posture in the light. That someone else was Queenie. The place had only one spotlight and it always shone on her.

Rumor had it that she was out of Chicago. But back at that movie premiere, she’d mentioned St. Louis. All anybody really knew was that she’d appeared out of nowhere. That was late last summer. It was midwinter now and she had developed a following.

You had to give it to her: Queenie Lovetree commanded that stage the moment she stepped foot on it. Every soul in the place turned toward her and stayed that way, flat-out mesmerized and a bit intimidated too. Only a fool would risk Queenie’s ire by talking when she had the mic.

A six-piece orchestra, one that included jazz violinist Max Bearden and cornetist Joe Mascarpone, backed her up. Her musicians were good—you had to be to play with Queenie—but not too good. She shared center stage with no one.

At six-foot-three, Queenie Lovetree was the tallest badass chanteuse most folks had ever seen. She had a toughness about her, a ferocity that kept fools in check. And yes, she was beautiful. She billed herself as the “Black Orchid.” The name fit. She was powerful, mythic, and rare.

Men were going crazy over her. They showered her with jewels and furs and offered to buy her cars or take her on cruises. In all the madness, many seemed to forget or stubbornly chose to ignore a most salient fact, the one secret that her beauty, no matter how artful, failed to hide: that Queenie Lovetree wasn’t a woman at all, but a man in drag.

When Queenie appeared on stage, sheathed in one of his tight, glittering gowns, he presented a near-perfect illusion of femininity. He could swish better than Mae West. His smile was dirtier, his curves firmer, and his repartee deadlier than a switchblade. From head to toe, he was a vision of feminine pulchritude that gave many a man an itch he ached to scratch.

That night, Queenie wore a dress with a slit that went high on his right thigh. Folks said he packed a pistol between his legs, the .22-caliber kind. If so, you couldn’t see it. You couldn’t see a thing. Queenie kept his weapons tucked away tight.

Gun or no gun, he smoked. When he took that mic, the folks hushed up and Queenie launched into some of the most down and dirty blues I’d ever heard. He preached all right, signifying for everything he was worth, and that crowd of mostly rich white folk, they ate it up.

During the set, Lucien Fawkes, the club’s owner, stopped by my table. He was a short, wiry Parisian, with hound-dog eyes, thin lips, and deep creases that lined his cheeks.

“Always good to see you, Lanie. You enjoying the show?”

“I’m enjoying it just fine.”

“I’ll tell the boys: anything you want, you get.”

After Queenie finished his set, the offers and invitations to join tables poured in. He took exuberant pleasure in accepting them, going from table to table. But that night, they weren’t his priority. He air-kissed a few cheeks, exchanged a few greetings, and then slunk over to join me.

“The suckers love me,” he said. “What about you?”

“I’m not a sucker.”

“Well, I know that, Slim. That’s why you’re having drinks on the house and they’re not.”

He sat down and turned to the serious business of wooing a reporter. “So, what do you think? Am I fantastic or am I fantastic?”

“I’d say you’ve got a good thing going.”

“You make it sound like I’m running a scam.”

I hadn’t meant it that way, but given his fake hair, fake eyelashes, and fake bosom, I could see why he thought I had. “I’m just saying you’re perfect for this place and it’s perfect for you. Everybody’s happy.”

“It’s okay,” he said. “For now.”

“You have plans for bigger and better things?”

“What if I do? There’s nothing wrong with that.”

“Not a thing. I’ve always admired ambitious, hard-working people.”

“Honey, I ain’t nothing if not that.” He leaned in toward me. “People say you’re the one to know. That you are the one to get close to if somebody’s interested in breaking out, climbing up. Because of that column of yours. What’s it called?”

“‘Lanie’s World.’”

“That’s right. ‘Lanie’s World.’” He savored the words. “And you write for the

Harlem Chronicle

?”

“Mm-hmm.”

“You think you can write a nice piece on me?”

“Well,” I hesitated. “There

is

some small amount of interest in you, but—”

“Small? People are crazy about me. The letters I get, the questions. They want to know all about me. Where I come from, what I like, what I don’t, what I eat before going to bed.”

I shrugged. “But they’ve heard so many different stories that—”

“I promise to tell you the whole truth and nothing but.”

“Well, thanks.”

I’d been in the journalism game for more than ten years. I’d worked as a crime reporter, interviewing victims and thugs, cops and dirty judges. Then I’d moved to society reporting, where I wrote about cotillions and teas, parties and premieres. It seemed like a different crowd, but the one constant was the mendacity. People lied. Sometimes for no apparent reason, they obfuscated, omitted, or outright obliterated the truth. And often the first sign of an intention to lie was an unsolicited promise to tell the truth, “the whole truth and nothing but.”