Black Pearls (19 page)

Authors: Louise Hawes

I placed my thumb on her wrist and my ear to her breastâ

how many times in the years ahead was I to find my head against that precious pillow, hearing nothing but my own racing heart! My brothers closed around us, expectant, hushed. I told them she was neither dead nor alive, but gripped by a poison that had stolen her faculties and sealed her body like a tomb.

We put her to bed as we had when she first came to us, stretching her across a pallet by the hearth. It was not until she was covered with all the blankets we could find, until she slept like a frozen bird beside the grate, that I heard the strange roar start up among us. When the rest drew back silently and left me standing alone beside her, I realized it was me I'd heard, wailing like a wolf and beating my fists against the hob.

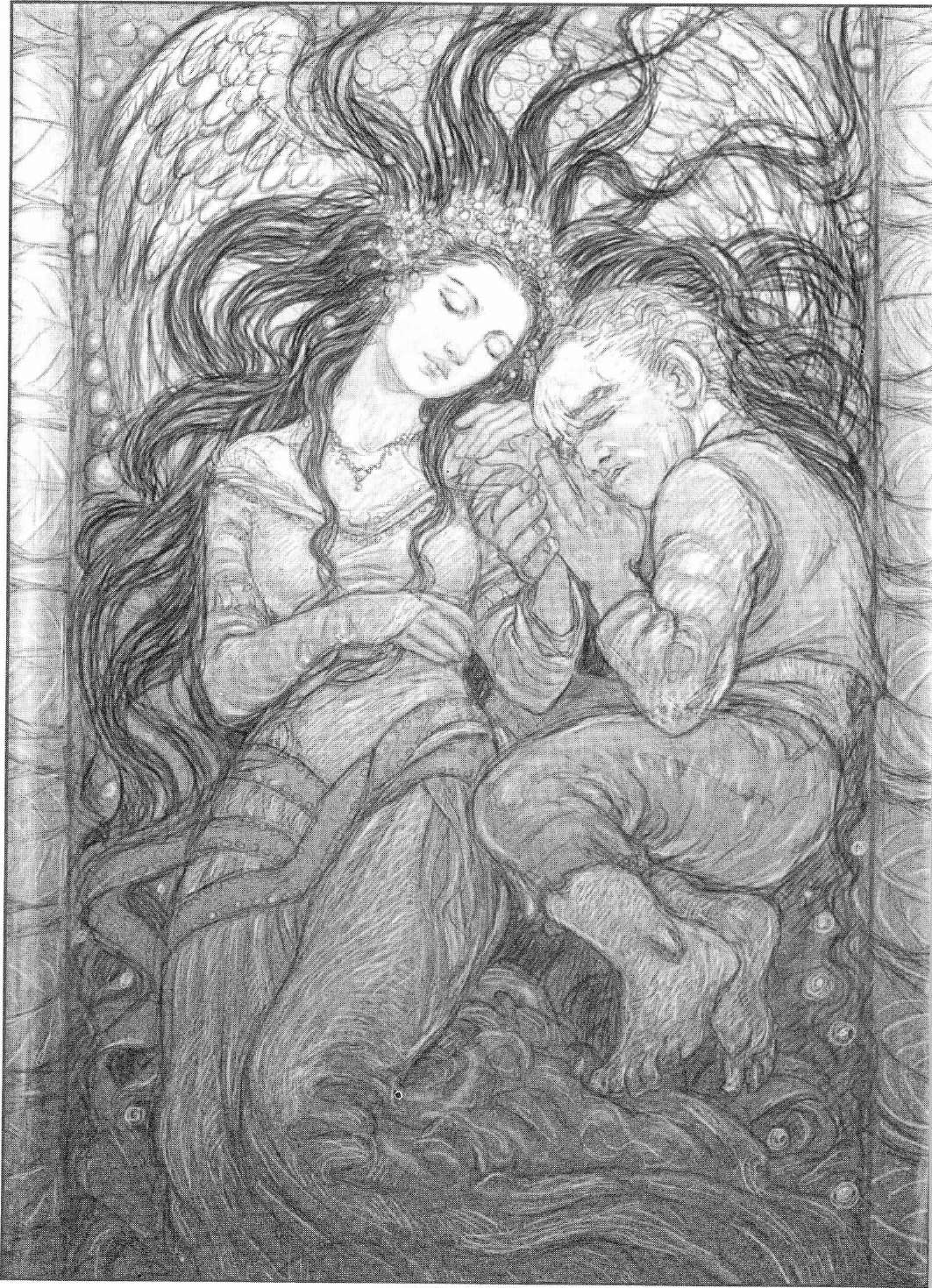

It was Ferin, always best with his hands, who built the crystal cocoon in which we placed her. "What if there is a change?" he had asked. "What if she wakes and needs us? Erin says she isn't dead, and I will not bury her alive." So we felled a maple, and he carved a bed for her. While he fashioned wooden angels and rosebuds, the rest of us contented ourselves with bringing home what gems we could and setting them in a necklace for her to wear. When the bed was done and we had laid her in it, Ferin covered her with a casket all paned in glass so we would be sure to notice if she stirred.

Fearful lest the queen discover our sleeping treasure, we hid her bier in a small shed behind the cottage. There, each of us in turn stood guard beside her, waiting for miracles. But Diamonda never moved. As winter withdrew slowly like a beaten cat, and green buds pushed through the forest floor, she dreamt on, unchanged. When the woods around her sounded with restless mating calls, she lay as beautiful and perfect as a stone saint in church. When spring had spent its promise and summer, too, we kept a fire going and wrapped our hands in wool while Diamonda felt no chill. At last, when ice stretched once more the length of Fairny Pond, only the seven of us were a year older than when we had laid her in her bier.

I kept the juice of the apple in a stoppered vial. I mixed herbs, concocted tinctures to find an antidote for the poison it contained. As the years passed, scores of squirrels and rabbits met their death at my well-intentioned hands. First I would poison the little beasts and then work my latest cure. All to no avail. It gave me hope, though, this foolish doctoring; it convinced me that I worked for her recovery. For as long as I kept meddling with my potions and powders, I told myself, I was surely as anxious as the others for Diamonda's deliverance.

Though, in truth, I had less reason to be. Because so long as she lay still and lifeless, I could be with her the way a manâa real manâwas meant to be with a woman. Or very nearly. As nearly as a repulsive dwarf dared. If it has been torture to remember this, then it is damnation to tell.

For whenever it was my time to stand guard at her bed, I lay beside her instead. How could I see her, desirable beyond endurance, and not lift the cover that separated us? How could I stoop to kiss her cheek and not beg her forgiveness by burying my face in her breast?

It was always the same. I began by swearing I would not come near her. I stood at one end of the hut while she lay, streaming radiance, at the other. I told myself I could do as the others did, could serve my love without demeaning her. And so I clung to my side of the tiny room, wrestling demons that would have given a giant a stout match. When I turned, it was only because I thought perhaps she had wakened and might need me. All innocent concern, I would make my way to her side and lean over just to make certain she had not called faintly from beneath the glass.

She had not called, of course, but lay as always, a candied sweet. The jewels we had scavenged from our poor mine seemed cloudy against her lustrous throat. Day after day, the hope was fresh each time I looked inside the glass, each time I watched for the damp print of breath on its face. And so, telling myself I might have missed her cry, her muffled call, I swung open the casket and bent to feel her pulse.

Once so close, I kindled like an oil-fed blaze. Perm had made her bed long and broad, broad enough for two. Tingling with shame and a rough, unstoppable need, I climbed in beside her. Too late then to curb the hunger that guided my fingers. Too late to reprimand the wicked, insatiable dwarf who stroked and kissed and licked. Her hands, her face, her perfect breasts that waited just beneath the corded neckline of her loosened gown.

Is there a reward for taking the devil's hand but refusing to

dance? Is there a place in hell, less loathsome than the rest, for those too small of soul to finish the evil they begin? If so, I am spared the ultimate punishment that would be mine if I had once been able to take Diamonda in her bier the way I did each night in my restless, guilt-stained sleep.

Because I did not. Always, when I reached lower and, with a thousand tears and apologies, began to lift her skirts, I saw not my own dream but hers. As I touched her, shaking with fervor, I watched my hand become large and fine. The fingers lengthened and straightened into those of someone else, the palms grew lineless and white. And as I tried to lower myself onto her, I felt my body change. My legs were charged with power, thick and long and coiled with strength; my arms lost their withered crook and looked as smooth and graceful as an acrobat's.

And my face? I cannot tell you bow I saw it, but I did. And I felt the transformation as clearly as you feel an icy spring rush against your skin. My bloated head grew slender, handsome, my eyes and nose as perfect as Diamonda's. I was, for a moment, what I had always yearned to beâDiamonda's dream. Locked inside this new and chiseled form, I watched my sweet love reach out to me. She stirred in her sleep and put her arms around me. But as she drew me to her, blind and doting, the horrible dwarf twisted free and ran from the hut to stand sobbing with his back against the wall until his watch had ended.

Year after year, her dream vanquished me. Night after night, I lay in my bed, rubbing and rocking, while Diamonda, chaste still, waited for her prince. If I had been the one on watch when he came, I would have known him, disguised or not. As it was, he wore a deep-hooded cloak and told Gwiffert he was a healer from Wainport across the mountain. By the time my brother had raced to the house to fetch us, the stranger had the casket open and was holding her in his arms.

He had thrown the cloak back from his face, and his light, curly hair was like a flame above the dark tangle of hers. His features were as I had always seen themâbright, comely, and ripe with enchantment. She was already awake and looked, for one dazed moment, away from her redeemer toward the seven manikins clustered at her waist.

As she turned, so did he, and twin suns beamed down on us. Her lips parted but she did not speak, as if she had forgotten during her long sleep how to form words. Then, after roving over us all, her eyes seemed to fix on me. A nameless shadow darkened her smile, and the shame of my old longing swept me.

"How long have I been sleeping?" Now her eyes found his again, though we could have answered her better.

"They say for years, my lady," he told her, his gaze locked on her face as if it were the north star. "Though, to tell the truth, I think I have slept all my life until now."

She laughed. It was not the same delicate, embarrassed laugh I remembered, but long and sparkling and laced with delight. "It seemed like no time," she told him. "I dreamed of you and did not want to wake."

***

Now she lives with him. Sleeps beside him and wakes when he does, her legs tangled with his, her hair caught under the pillow they share. When he holds tribunal, he keeps her next to him and will not render judgments until she and he agree. Sometimes, when she questions his decision, they argue and draw apart, strange, hooded looks clouding them. But it is nothing, a storm in a summer garden, the confusion of leaves before they fall and lie together, limp and spent. Diamonda dreamed him before they met, brought him with her out of her dark sleep, and cannot live except in his light.

So when she visits us, he comes, too. And when she sits with me, as she did today, sipping tea in her old place by the fire, he sits, too, folded improbably into a small chair near hers. At times he watches her face when she speaks, at others he turns toward me, his shoulder brushing hers, easy and familiar with her touch. At last he stands, smoothing his doublet and taking her hand. She begs for a few more minutes, pouting prettily as he pulls her toward the door.

So they are gone and my brothers have dragged themselves to bed, logy with the cakes and sweetmeats she brought. They chatter in the loft a while, like nesting birds, then settle into sleep. I tiptoeâthough all the bells in Haywick could not wake that welbfed crewâto the hearth. I loosen the stone that hides the bottle, then hold the wine-colored poison to the firelight. It shimmers like an amethyst in my hand.

The fire mutters to itself and somewhere outside a dove whisties drowsily to its mate. In all the years Diamonda slept, I never missed her as I do now. How I loathe myself for wishing she were still waiting for me beneath the glass! Should I drink to the stunted passion which prefers a caged bird to one that flies?

I open the door and carry the bottle with me to the hut. The moon is a regretful rind as I turn the key, then stand beside her old bed. Under the glass on the silk sheet is a long black shadow where she used to lie. Shall I drink to the ghost of yearning that stirs in me even now?

The casket's cover is heavier than I remember, or perhaps my trembling only makes it seem so. I put the bottle on a table, push the cover back on its hinges, and smooth her sheet with my hand. Her spot is icy cold, her warmth is somewhere else tonight. Perhaps I should drink to my six brothers, who will weep dwarf tears when they find me here.

I take off my boots and, with an old eagerness, let myself down. Instead of lying to one side, though, I take her place, my head where hers used to be, my feet straining toward the angels at the bottom of the bed. Through the open door, I see the slice of moon and hear a mouse or fox shuffle dry leaves across its path. My hand just reaches the bottle. I raise it to my lips and down it all, then close the casket's cover. Here's to the dreams that will sear my sleep when Diamonda mourns for me and presses tight against the glass.

Ride a cock horse to Coventry Cross,

to see a fine lady upon a white horse,

rings on her fingers and bells on her toes,

she shall have music wherever she goes.

They are wrong, you know. I wore no jewels when Fidelity and I rode through Coventry. The children in town still sing this song, but they are far too young to remember how it truly happened. And I am far too old to tell you a lie, close as I am to the grave. The horse was gray, not white. And the lady wore neither rings, nor cape, nor gown.

Coventry was only a small village then, and most of its families were known to me and to my lord, Leofric of Mercia. It is due to the discretion and tender feelings of those good folk, and to the love of a single child, that the nursery rhyme fails to mention the strange circumstances of my ride. The time has come, though, to strip away such lies and to let truth, as the old psalmist says, be my shield.

Leofric was wont to tell me, in those days, that I took the woes of commoners too much to heart. "You are, my precious Godiva, inclined to weep overmuch for peasants and dumb animals, none of whom will shed a single tear for you."

"It is not with hope of return," I told him, "that I aid those less fortunate than ourselves." I remembered the eyes of the littie ones when I threw coins into the streets on feast days. "It is for the sheer joy it brings me."

And, I should have added, for the absolution. It was, after all, not pleasure but forgiveness I sought the day I saddled Felicity with the stable boy's blanket instead of the silver harness to which she was accustomed. It was to erase a sin that I mounted her and rode into town without the silk and jewels by which the people knew me. And it was as a penitent that I dismounted, freighted with a secret treasure, at the small cottage where Ebba was being born.

When it was new, Coventry boasted only a single street, a long path that wound in a circle around the town, then worked its way to the river Cune on one side and to the forest of Arden on the other. The house I sought that morning was halfway around the circle, and so I was forced to pass some forty thatched huts before I reached it. Few of those poor homes had windows, but they all had doors. Soon villagers were running from one house to another, and more and more doors began to open along my way.

Some village folk came into the street to stare, others watched from their doors, and still others turned away as if it hurt to look on me. All of them were silent, hushed by the fire in my eyes and the shock of my bare legs against the horse's sides, my naked shoulders and breasts. I was too numb with righteous anger and hurt pride to notice their expressions, to care if one was lusty or another shamed, but I remember still the old man who stepped into my path to grab hold of Felicity's bridle. He was palsied and trembling, but he held the horse fast until he had made the sign of the cross in front of my face. Then, God's work done, he fell back to let me pass.