Black Queen (6 page)

Authors: Michael Morpurgo

The next few days were not good, not good at all. I found it more and more difficult to find the right moment to sneak off and feed Rambo. It wasn’t that anyone was suspicious, it was just that there was someone else in the house. Gran had come to stay with us in our new home for the first time, so that meant there was another pair of eyes I had to dodge. But somehow I managed to sneak away unseen each day, slip in behind the garden shed and scramble over into the Black Queen’s garden. Once inside her garden I felt safe enough. But now every time I went into Number 22 I was troubled by a terrible temptation. I had this deep urge inside me to sneak about the house looking for evidence to confirm my theory about her son. I longed to peek into one of the front rooms, or even creep up the stairs into the bedrooms. But I just didn’t dare. I was too frightened – frightened that someone might see me through a window; but more than that, I was frightened of the house. I didn’t like being in there. It was dark and empty and cold – just like the haunted house of my dreams. Every time I went inside I just wanted to feed Rambo and get out as quickly as possible.

Feeding Rambo was never a problem. As soon as I was dressed up in the coat and floppy hat with the glasses on, he seemed to accept me totally as Mrs Blume, as the Black Queen. He loved me to bits. He’d even try to follow me back up the steps into the house. I had to shoo him away. I kept an eye out all the while for Rula. But I think I must have succeeded in frightening her off, for her face never again reappeared over the fence.

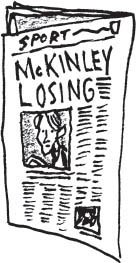

The news from New York was not good. Purple had won the first four

matches.

I kept thinking how disappointed the Black Queen must be, going all that way to New York just to watch her son lose.

Every time Greg McInley lost my father became more depressed. He’d read about it in the newspapers and come away miserable. “It’s not like him, Billy,” he’d say, “not like him at all. He keeps making mistakes, elementary mistakes. Greg McInley never makes mistakes.” Then he’d blame Purple. “It’s that lousy computer fazing him out somehow. He’ll do better tomorrow, you’ll see.”

But tomorrow was always just as bad. Soon it was six matches to nil. If Greg McInley lost the next day, then that would be the end of it.

But the next day the real action moved from New York to back home. I was feeding Rambo late that afternoon when I saw Matey sitting in the long grass of Number 22, nibbling busily. He must have found another way through. Rambo hadn’t even seen him – he was oblivious to everything except his food. I thought I’d act quickly before Rambo saw him, before someone came looking. I ran down the steps, picked up Matey, clambered up onto the rusty roller by the garden fence and looked over. Rula was just coming out into the garden, crying her eyes out and calling for Matey.

It was risky, but I was so into the part that I knew I could fool her. “Hey, kid,” I called out. “You lost something?”

She stopped crying the moment she saw me and began to back away. “Matey,” she said, “my rabbit. I can’t find my rabbit.”

I held up Matey by the scruff of his neck. “This what you’re looking for?” I asked.

I could see she was still nervous of me, but all the same she came over, reached up and took him from me. I don’t think she dared even look at me – which was just as well, I suppose.

“Thank you,” she said, clutching him tight, and she ran off at once back into the house.

I was in the kitchen a few minutes later just taking off my floppy hat when I heard the bell ring, the front door bell. I stood there, hardly daring to breathe. The bell went again.

“Anyone home?” It was my mother! I heard Rula’s voice too! Both of them were there. And Rula knew I was in

that

house, she’d only just seen me. I

had

to be there.

There was no way out. I had to say something. I made it up as I went along. “Listen,” I called out. “It’s a bit difficult. I’m washing my hair right now, OK?” I sounded just like her, the Black Queen, just like a woman, just like a real American.

“It’s all right,” my mother replied. “We didn’t want to bother you. Rula and me, we just wanted to say thank you, that’s all, for finding Rula’s rabbit for us.”

“No problem,” I said.

“Maybe you’d like to come over sometime,” my mother went on.

“That’d be fine,” I said, “just fine. Thanks.”

And then they were gone. I could not believe it. I had fooled my own mother. I was brilliant, utterly brilliant; but I was shaking like a leaf.

Chapter 7

Hide and Seek

THE NEXT DAY

we heard that Greg McInley had beaten Purple for the first time, and once he’d started winning he didn’t stop. Whenever the news came on breakfast television we’d be watching, all of us – Gran included, and she’d always said that chess was the most boring game there ever was.

Until now chess had been just a game for me – a game I enjoyed, but still just a game. Now it was becoming an

obsession.

For me, for my own private reasons, even more than for everyone else in the house, the result of a chess match between a man and a computer had become more important than a football World Cup final. Every day I was aching to tell them who the Black Queen was, that we had Greg McInley’s mother living next door to us. But I could not bring myself to do it. It wasn’t that I was frightened of her any more – she could hardly be a witch

and

Greg McInley’s mother, could she? But I had promised her I’d say nothing and she trusted me – she’d said so. And besides, I knew that once I told them that, then I’d have to tell them everything. I’d have an awful lot to explain away. So I kept quiet, but it was hard, so hard.

When, after five more wins, we heard that Greg McInley had drawn level with Purple at six matches each, we all went berserk, leaping up and down like wild

things,

so much so that Matey went and hid under the sofa.

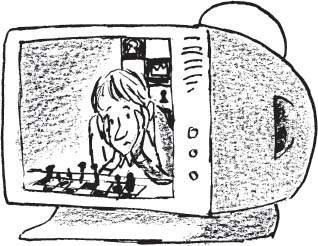

Now it was on the television all the time, every news bulletin. And we weren’t the only ones getting excited. Of course they only ever showed the last few moves of each match. Greg McInley would be sitting up there on a dimly lit stage, a great electronic chessboard behind him. He’d be hunched over the table like a concert pianist, his nose almost touching the chess pieces on the board. When he moved a piece he always did it in precisely the same way.

He’d

sit back, brush his nose with his forefinger, then reach out very decisively. He’d tap the piece he was going to move three times, always three times, move it, punch the timeclock and sit back, then fold his arms and wait for Purple’s move to come up on the electronic board. When Greg McInley won there were no fists raised in the air in triumph, no smiles even. He’d just push his chair back and walk directly off the stage, completely ignoring the audience who’d be on their feet, clapping and cheering. I

always

looked for a glimpse of his mother in the audience. And I thought I did see her just once, a woman in black in the front row, but the camera passed by her so quickly that I couldn’t be sure.