Black Swan Green (4 page)

Authors: David Mitchell

Time went by, I s’pose.

The sour aunt held a china bowl in one hand and a cloudy glass in the other. ‘Take off your sock.’

My ankle was balloony and limp. The sour aunt propped my calf on a footstool and knelt by it. Her dress rustled. Apart from the blood in my ears and my jagged breathing there was no other sound. Then she dipped her hand into the bowl and began smearing a bready goo on to my ankle.

My ankle shuddered.

‘This is a poultice.’ She gripped my shin. ‘To draw out the swelling.’

The poultice sort of tickled but the pain was too vicious and I was fighting the cold too hard. The sour aunt smeared the goo on till it was used up and my ankle’d completely clagged. She handed me the cloudy glass. ‘Drink this.’

‘It smells like…marzipan.’

‘It’s for drinking. Not smelling.’

‘But what is it?’

‘It’ll help take the pain away.’

Her face told me I had no real choice. I swigged back the liquid in one go like you do Milk of Magnesium. It was syrupy-thick but didn’t taste of much. I asked, ‘Is your brother asleep upstairs?’

‘Where else would he be, Ralph? Shush now.’

‘My name’s not Ralph,’ I told her, but she acted like she hadn’t heard. Clearing up the misunderstanding’d’ve been a massive effort and now I’d stopped moving I just couldn’t fight the cold any more. Funny thing was, as soon as I gave in, a lovely drowsiness tugged me downwards. I pictured Mum, Dad and Julia sitting at home watching

The Paul Daniels Magic Show

but their faces melted away, like reflections on the backs of spoons.

The cold poked me awake. I didn’t know where or who or when I was. My ears felt bitten and I could see my breath. A china bowl sat on a footstool and my ankle was crusted in something hard and spongey. Then I remembered everything, and sat up. The pain in my foot had gone but my head didn’t feel right, like a crow’d flown in and couldn’t get out. I wiped the poultice off my foot with a snotty hanky. Unbelievably, my ankle swivelled fine, cured, like magic. I pulled on my sock and trainer, stood up and tested my weight. There was a faint twinge, but only ’cause I was looking for it. Through the beaded doorway I called out, ‘Hello?’

No answer came. I passed through the crackly beads into a tiny kitchen with a stone sink and a

massive

oven. Big enough for a kid to climb in. Its door’d been left open, but inside was as dark as that cracked tomb under St Gabriel’s. I wanted to thank the sour aunt for curing my ankle.

Make sure the back door opens

, warned Unborn Twin.

It didn’t. Neither did the frost-flowered sash window. Its catch and hinges’d been painted over long ago and it’d take a chisel to persuade it open, at least. I wondered what the time was and squinted at my granddad’s Omega but it was too dark in the tiny kitchen to see. Suppose it was late evening? I’d get back and my tea’d be waiting under a Pyrex dish. Mum and Dad go

ape

if I’m not back in time for tea. Or s’pose it’d gone midnight? S’pose the police’d been alerted?

Jesus

. Or what if I’d slept right through one short day and into the night of the next? The

Malvern Gazetteer

and

Midlands Today

’d’ve already shown my school photo and sent out appeals for witnesses.

Jesus

. Squelch would’ve reported seeing me heading to the frozen lake. Frogmen might be searching for me there, right now.

This was a bad dream.

No, worse than that. Back in the parlour, I looked at my grandfather’s Omega and saw that there

was

no time. My voice whimpered, ‘

No

.’ The glass face, the hour hand and minute hand’d gone and only a bent second hand was left. When I fell on the ice, it must’ve happened then. The casing was split and half its innards’d spilt out.

Granddad’s Omega’d never once gone wrong in forty years.

In less than a fortnight, I’d killed it.

Wobbly with dread, I walked up the hallway and hissed up the twisted stairs, ‘Hello?’ Silent as night in an ice age. ‘I have to go!’ Worry about the Omega’d swatted off worry about being in this house, but I still daredn’t shout in case I woke the brother. ‘I’ve got to go home now,’ I called, a bit louder. No reply. I decided to just leave by the front door. I’d come back in the daytime to thank her. The bolts slid open easily enough, but the old-style lock was another matter. Without the key it wouldn’t open. That was that. I’d have to go upstairs, wake the old biddy to get her key and if she got annoyed that was just tough titty. Something,

something

, had to be done about the catastrophe of the smashed watch. God knows what, but I couldn’t do it inside the House in the Woods.

The stairs curved up steeper. Soon I had to use my hands to grip the stairs above me, or I’d’ve fallen back. How on

earth

the sour aunt went up and down in that big rookish dress was anybody’s guess. Finally, I hauled myself on to a tiny landing with two doors. A slitty window let in a glimmer. One door had to be the sour aunt’s room. The other had to be the brother’s.

Left’s got a power that right hasn’t so I clasped the iron door knob on the left. It sucked the warmth from my hand, my arm, my blood.

Scrit-scrat

.

I froze.

Scrit-scrat

.

A death-watch beetle? Rat in the loft? Pipe freezing up?

Which room was the

scrit-scrat

coming from?

The iron door knob made a coiling creak as I turned it.

Powdery moonlight lit the attic room through the snowflake-lace curtain. I’d guessed right. The sour aunt lay under a quilt with her dentures in a jar by her bed, still as a marble duchess on a church tomb. I shuffled over the tipsy floor, nervous at the thought of waking her. What if she forgot who I was and thought I’d come to murder her and screamed for help and had a stroke? Her hair spilt over her folded face like pondweed. A cloud of breath escaped her mouth every ten or twenty heartbeats. Only that proved she was made of flesh and blood like me.

‘Can you hear me?’

No, I’d have to shake her awake.

My hand was halfway to her shoulder when that scrit-scrat noise started up again, deep inside

her

.

Not a snore. A death rattle.

Go into the other bedroom. Wake her brother. She needs an ambulance. No. Smash your way out. Run to Isaac Pye in the Black Swan for help. No. They’d ask why you’d been in the House in the Woods. What’d you say? You don’t even know this woman’s name. It’s too late. She’s dying, right now. I’m certain. The scrit-scrat’s uncoiling. Louder, waspier, daggerier.

Her windpipe bulges as her soul squeezes out of her heart.

Her worn-out eyes flip awake like a doll’s, black, glassy, shocked.

From her black crack mouth, a blizzard rushes out.

A silent roaring hangs here.

Not going anywhere.

Dark

, light,

dark

, light,

dark

, light. The Datsun’s wipers couldn’t keep up with the rain, not even at the fastest setting. When a juggernaut passed the other way, it slapped up spumes on to the streaming windscreen. Through this car-wash visibility I only

just

made out the two Ministry of Defence radars spinning at their incredible speed. Waiting for the full might of the Warsaw Pact forces. Mum and me didn’t speak much on the way. Partly ’cause of where she was taking me, I think. (The dashboard clock said 16:05. In seventeen hours

exactly

my public execution’d take place.) Waiting at the Pelican crossing by the closed-down beautician’s she asked me if I’d had a good day and I said, ‘Okay.’ I asked her if she’d had a good day too and she said, ‘Oh, sparklingly creative and deeply fulfilling, thank you.’ Dead sarky, Mum can be, even though she tells me off for it. ‘Did you get any Valentine’s cards?’ I’d said no, but even if I’d had some I’d’ve told her no. (I did get one but I put it in the bin. It said ‘Suck My Dick’ and was signed by Nicholas Briar, but it looked like Gary Drake’s handwriting.) Duncan Priest’d got four. Neal Brose got seven, or so he reckons. Ant Little found out that Nick Yew’d got

twenty

. I didn’t ask Mum if she’d got any. Dad says Valentine’s Days and Mother’s Days and No-armed Goalkeeper’s Days’re all conspiracies of card manufacturers and flower shops and chocolate companies.

So anyway, Mum dropped me at Malvern Link traffic lights by the clinic. I forgot my diary in the glove compartment and if the lights hadn’t turned red for me, Mum would’ve driven off to Lorenzo Hussingtree’s with it. (‘Jason’ isn’t exactly the acest name you could wish for but any ‘Lorenzo’ in

my

school’d get Bunsen-burnered to death.) Diary safe in my satchel, I crossed the flooded clinic car park leaping from dry bit to dry bit like James Bond froggering across the crocodiles’ backs. Outside the clinic were a couple of second- or third-years from the Dyson Perrins School. They saw my enemy uniform. Every year, according to Pete Redmarley and Gilbert Swinyard, all the Dyson Perrins fourth-years and all our fourth-years skive off school and meet in this secret arena walled in by gorse on Poolbrook Common for a mass scrap. If you chicken out you’re a homo and if you tell a teacher you’re

dead

. Three years ago, apparently, Pluto Noak’d hit their hardest kid so hard that the hospital in Worcester’d had to sew his jaw back on. He’s still sucking his meals through a straw. Luckily it was raining too hard for the Dyson Perrins kids to bother with me.

Today was my second appointment this year so the pretty receptionist in the clinic recognized me. ‘I’ll buzz Mrs de Roo for you now, Jason. Take a seat.’ I like her. She knows why I’m here so she doesn’t make pointless conversation that’ll show me up. The waiting area smells of Dettol and warm plastic. People waiting there never look like they have much wrong with them. But I don’t either, I s’pose, not to look at. You all sit so close to each other but what can any of you talk about ’cept the thing you want to talk about least: ‘So, why are

you

here?’ One old biddy was knitting. The sound of her needles knitted in the sound of the rain. A hobbity man with watery eyes rocked to and fro. A woman with coat-hangers instead of bones sat reading

Watership Down

. There’s a cage for babies with a pile of sucked toys in it, but today it was empty. The telephone rang and the pretty receptionist answered it. It seemed to be a friend, ’cause she cupped the mouthpiece and lowered her voice.

Jesus

, I envy

anyone

who can say what they want at the same time as they think it, without needing to test it for stammer-words. A Dumbo the Elephant clock tocked this:

to

–

mo

–

rrow

–

mor

–

ning’s

–

com

–

ing

–

soon

–

so

–

gouge

–

out

–

your

–

brain

–

with

–

a

–

spoon

–

you

–

can

–

not

– e –

ven

–

count

–

to

–

ten

–

be

–

gin

–

a

–

gain

–

a

–

gain

–

a

–

gain

. (Quarter past four. Sixteen hours and fifty minutes to live.) I picked up a tatty

National Geographic

magazine. An American woman in it’d taught chimpanzees to speak in sign language.

Most people think stammering and stuttering are the same but they’re as different as diarrhoea and constipation. Stuttering’s where you say the first bit of the word but can’t stop saying it over and over.

St

-

st

-

st

-

st

utter. Like that. Stammering’s where you get stuck straight after the first bit of the word. Like this.

St

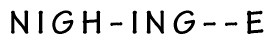

…AMmer! My stammer’s why I go to Mrs de Roo. (That really is her name. It’s Dutch, not Australian.) I started going that summer when it never rained and the Malvern Hills turned brown, five years ago. Miss Throckmorton’d been playing Hangman on the blackboard one afternoon with sunlight streaming in. On the blackboard was

Any

duh

-brain could work that out, so I put up my hand. Miss Throckmorton said, ‘Yes, Jason?’ and

that

was when my life divided itself into Before Hangman and After Hangman. The word ‘nightingale’ kaboomed in my skull but it just

wouldn’t come out

. The ‘N’ got out okay, but the harder I forced the rest, the tighter the noose got. I remember Lucy Sneads whispering to Angela Bullock, stifling giggles. I remember Robin South staring at this bizarre sight. I’d’ve done the same if it hadn’t been me. When a stammerer stammers their eyeballs pop out, they go trembly-red like an evenly matched arm wrestler and their mouth guppergupperguppers like a fish in a net. It must be quite a funny sight.

It wasn’t funny for me, though. Miss Throckmorton was waiting. Every kid in the classroom was waiting. Every crow and every spider in Black Swan Green was waiting. Every cloud, every car on every motorway, even Mrs Thatcher in the House of Commons’d frozen, listening, watching, thinking,

What’s

wrong

with Jason Taylor?

But no matter how shocked, scared, breathless, ashamed I was, no matter how much of a total flid I looked, no matter how much I

hated

myself for not being able to say a simple word in my own language, I

couldn’t

say ‘nightingale’. In the end I had to say, ‘I’m not sure, miss,’ and Miss Throckmorton said, ‘I see.’ She did see, too. She phoned my mum that evening and one week later I was taken to see Mrs de Roo, the speech therapist at Malvern Link Clinic. That was five years ago.

It must’ve been around then (maybe that same afternoon) that my stammer took on the appearance of a hangman. Pike lips, broken nose, rhino cheeks, red eyes ’cause he never sleeps. I imagine him in the baby room at Preston Hospital playing

Eeny-meeny-miny-mo

. I imagine him tapping my koochy lips, murmuring down at me,

Mine

. But it’s his hands, not his face, that I really feel him by. His snaky fingers that sink inside my tongue and squeeze my windpipe so nothing’ll work. Words beginning with ‘N’ have always been one of Hangman’s favourites. When I was nine I dreaded people asking me ‘How old are you?’ In the end I’d hold up nine fingers like I was being dead witty but I know the other person’d be thinking,

Why didn’t he just

tell

me, the twat?

Hangman used to like Y-words, too, but lately he’s eased off those and has moved to S-words. This is bad news. Look at any dictionary and see which section’s the thickest: it’s S. Twenty million words begin with N or S. Apart from the Russians starting a nuclear war, my biggest fear is if Hangman gets interested in J-words, ’cause then I

won’t even be able to say my own name

. I’d have to change my name by deed-poll, but Dad’d never let me.

The only way to outfox Hangman is to think one sentence ahead, and if you see a stammer-word coming up, alter your sentence so you won’t need to use it. Of course, you have to do this without the person you’re talking to catching on. Reading dictionaries like I do helps you do these ducks and dives, but you have to remember who you’re talking to. (If I was speaking to another thirteen-year-old and said the word ‘melancholy’ to avoid stammering on ‘sad’, for example, I’d be a laughing stock, ’cause kids aren’t s’posed to use adult words like ‘melancholy’. Not at Upton upon Severn Comprehensive, anyway.) Another strategy is to buy time by saying ‘Er…’ in the hope that Hangman’s concentration’ll lapse and you can sneak the word out. But if you say ‘er…’ too much you come across as a right dimmer. Lastly, if a teacher asks you a question directly and the answer’s a stammer-word, it’s best to pretend you don’t know. I couldn’t count how often I’ve done this. Sometimes teachers lose their rag (specially if they’ve just spent half a lesson explaining something) but

any

thing’s better than getting labelled ‘School Stutterboy’.

That’s something I’ve always

just

about avoided, but tomorrow morning at five minutes past nine this is going to happen. I’m going to have to stand up in front of Gary Drake and Neal Brose and my

entire

class to read from Mr Kempsey’s book,

Plain Prayers for a Complicated World

. There will be

dozens

of stammer-words in that reading which I

can’t

substitute and I

can’t

pretend not to know because there they are, printed there. Hangman’ll skip ahead as I read, underlining all his favourite N and S words, murmuring in my ear, ‘

Here

, Taylor, try and spit

this

one out!’ I

know

, with Gary Drake and Neal Brose and everyone watching, Hangman’ll

crush

my throat and

mangle

my tongue and

scrunch

my face up. Worse than Joey Deacon’s. I’m going to stammer worse than I’ve ever stammered in my life. By 9.15 my secret’ll be spreading round the school like a poison gas attack. By the end of first break my life won’t be worth living.

The gro

tes

quest thing I ever heard was this. Pete Redmarley swore on his nan’s grave it’s true so I s’pose it must be. This boy in the sixth form was sitting his A-levels. He had these parents from hell who’d put him under massive pressure to get a whole raft of ‘A’ grades and when the exam came this kid just cracked and couldn’t even understand the questions. So what he did was get two Bic Biros from his pencil case, hold the pointy ends against his eyes, stand up and head-butt the desk. Right there, in the exam hall. The pens skewered his eyeballs so deep that only an inch was left sticking out of his drippy sockets. Mr Nixon the headmaster hushed everything up so it didn’t get in the papers or anything. It’s a sick and horrible story but right now I’d rather kill Hangman that way than let him kill me tomorrow morning.

I mean that.

Mrs de Roo’s shoes clop so you know it’s her coming to fetch you. She’s forty or maybe even older, and has fat silver brooches, wispy bronze hair and flowery clothes. She gave a folder to the pretty receptionist, tutted at the rain and said, ‘My, my, monsoon season’s come to darkest Worcestershire!’ I agreed it was chucking it down, and left with her quick. In case the other patients worked out why I was there. Down the corridor we went, past the signpost full of words like

PAEDIATRICS

and

ULTRASCANS

. (No ultranscan’d read

my

brain. I’d beat it by remembering every satellite in the solar system.) ‘February’s

so

gloomy in this part of the world,’ said Mrs de Roo, ‘don’t you think? It’s not so much a month as a twenty-eight-day-long Monday morning. You leave home in the dark and go home in the dark. On wet days like these, it’s like living in a cave, behind a waterfall.’

I told Mrs de Roo how I’d heard Eskimo kids spend time under artificial sun-lamps to stop them getting scurvy, ’cause at the North Pole winter lasts for most of the year. I suggested Mrs de Roo should think about getting a sunbed.

Mrs de Roo answered, ‘I shall think on.’

We passed a room where a howling baby’d just had an injection. In the next room a freckly girl Julia’s age sat in a wheelchair. One of her legs wasn’t there. She’d probably love to have my stammer if she could have her leg back, and I wondered if being happy’s about other people’s misery. That cuts both ways, mind. People’ll look at me after tomorrow morning and think,

Well, my life may be a swamp of shit but at least I’m not in Jason Taylor’s shoes. At least I can

talk.

February’s Hangman’s favourite month. Come summer he gets dozy and hibernates through to autumn, and I can speak a bit better. In fact after my first run of visits to Mrs de Roo five years ago, by the time my hayfever began everyone thought my stammer was cured. But come November Hangman wakes up again, sort of like John Barleycorn in reverse. By January he’s his old self again, so back I come to Mrs de Roo.

This

year Hangman’s worse than ever. Aunt Alice stayed with us two weeks ago and one night I was crossing the landing and I heard her say to Mum, ‘

Honestly

, Helena, when are you going to do something about his

stutter

? It’s social suicide! I never know whether to finish the sentence for him or just leave the poor boy dangling on the end of his rope.’ (Eavesdropping’s sort of thrilling ’cause you learn what people really think, but eavesdropping makes you miserable for exactly the same reason.) After Aunt Alice’d gone back to Richmond, Mum sat me down and said it mightn’t do any harm to visit Mrs de Roo again. I said okay, ’cause actually I’d wanted to but I hadn’t asked ’cause I was ashamed, and ’cause mentioning my stammer makes it realer.