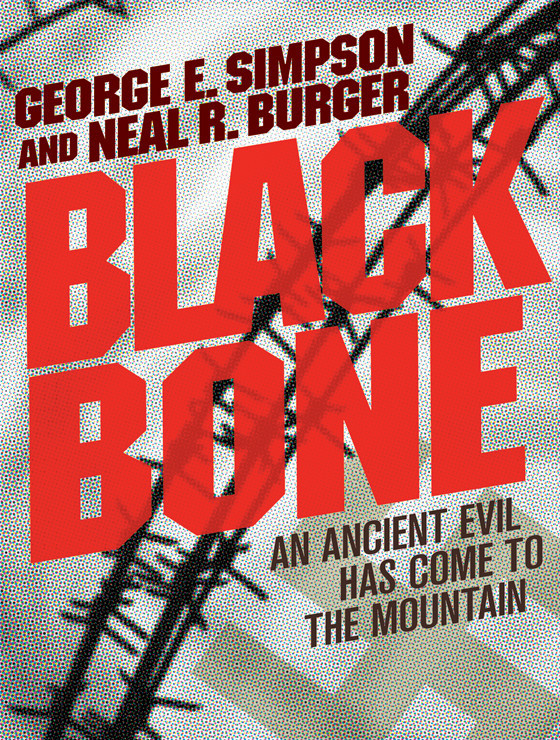

Blackbone

Blackbone

George E. Simpson

and

Neal R. Burger

Copyright © 1985 by George E. Simpson and Neal R. Burger

Published by E-Reads. All rights reserved.

www.ereads.com

Prologue

December 1944.

Leutnant Rolf Kirst plowed into the Atlantic with a stunning force that knocked the breath from his body.

He would have drowned then and there but for the buoyancy of his life preserver. It brought him to the surface, blinking salt-stung eyes, gulping air into tortured lungs. Horrified, he watched U-221, her conning tower and afterdeck a ruin of twisted steel, roll over and slip beneath the waves.

Kirst paddled furiously to escape the suction trying to drag him down with the boat. His mind raced to reconstruct the sequence of events that had catapulted him into the sea.

They had torpedoed the straggling Liberty Ship, then surfaced to finish her off with the deck gun. As gunnery officer, Kirst had been topside as his crew manned the 88- millimeter and pumped shell after shell into the stricken freighter, setting her ablaze from one end to the other.

How then had he ended up in the water?

Something roared over Kirst’s head. An American patrol bomber flashed by, its blue-white underside illuminated by the glow from the burning freighter. Kirst shook his head, trying to recall details. Position—at least four hundred miles off the eastern coast of the United States. Situation—bobbing in the Atlantic Ocean, imminently about to freeze or drown, whichever came first. He recalled his training, remembered the warnings—the icy waters could kill him in minutes.

He saw the crate break loose from a welter of smaller pieces of wood. It slid down a swell, riding high in the water.

Kirst lunged for it. Numbed fingers locked around hemp wrapping lines. He heaved himself out of the ocean and sprawled over rough planking, spreading his arms for balance, afraid that any abrupt weight shift would overturn the crate.

After a few minutes, Kirst realized that the crate was no lightweight empty box but contained some sort of cargo acting as ballast—watertight as well, or it would have sunk before now. If he could get it open, he might be able to crawl inside, out of the terrible cold.

Holding the wrapping lines in his left hand, he snaked his right down to his waist, found his sheath knife still attached to his belt, fumbled with the snap, then freed the blade.

He began sawing through the rope, realizing that once it was cut, he would have no handhold, but even more aware that if he didn’t get inside, he might as well give up now, let go, and slide beneath—

The blade was sharp. In a moment, the hemp fell away. The crate rocked suddenly and Kirst nearly fell off. Jamming his knife into the wood and using it as a handhold, he drew his legs up and reversed position. Pulling the knife out again, he cut the line on the other side of the crate, then flattened himself once again. His fingers groped for nails: there were none. What held the crate together? He peered at the wood beneath his cheek. Between the planks he discovered a line of caulking.

Cursing whoever had sealed the crate, Kirst inserted the tip of his blade between two planks, sliced through the caulking, then gently levered the wood. One plank edged loose. He sliced up more of the caulking, turned the blade, and levered again, widening the space. He shifted the knife and slipped his right hand through the opening. He pushed the wood. The plank slid out of the frame and into the water. The opening was still too small to climb through. He went to work on the next plank.

A series of explosions across the water buffeted him. The crate heaved and tipped crazily. His knife dropped through the opening. Kirst locked his fingers around the edge of the second plank to avoid being thrown back into the ocean.

Chunks of white-hot metal whizzed through the air and splashed around him. The Atlantic was taking the Liberty Ship down.

She sank with a final grace. Tortured metal groaned as it constricted in the frigid water. Rapidly diminishing bubbles spat out debris that shot into the air, then fell back into the sea. The remains became a moving carpet of charred wood and bits of cork. Kirst was in a sea of garbage.

When things settled, Kirst moved gingerly, retrieving his knife from inside the crate. He raised his body and wedged the blade into the seam between the second and third plank. Exerting the last of his strength and muttering a long-forgotten prayer, Kirst twisted the knife handle.

Slowly the wood yielded. A gap opened. Triumphantly, he slid the blade down and worked the plank loose. Then again he jammed the knife into the lid and used it as a handhold. He forced his arm into the gap and pushed. The second plank popped out and fell into the water.

Kirst rolled through the opening.

He landed on packing material—burlap and lumpy wadding. At least it was dry. The crate was picked up on the swells and tossed about, and Kirst was rocked around inside. His fingers explored the walls and he discovered that the crate was lined with sticky caulking. The smell was terrible, but to Kirst it surpassed the finest perfume. It meant life, safety, survival.

First he had to warm his chilled body. With cold air whistling through the open top, Kirst tunneled deeper and wrapped himself in a burlap cocoon, ignoring hard lumps beneath his exhausted body. Burlap scratched his face but, lulled by the rocking motion as the crate was pushed through long Atlantic swells, Kirst drifted into a deep sleep.

He awoke with a start. Several seconds later, he remembered where he was. He fought panic and tried to take stock. He was alive, but for how long? He shifted and discovered that his whole body ached from stiffness. And he was cold, bitterly cold. Through the opening, stars shimmered in the night sky. He tried to focus on the distant points of light, but the crate kept rocking and the stars danced like manic fireflies. Something painful dug into his thigh. He felt beneath his legs and found a small wooden box.

He pulled it up and realized he was lying on a stack of such boxes. Though his fingers were still sticky from handling the caulking, he managed to work the box open. With a muted clatter, a smooth flat object with rounded edges dropped onto the burlap.

By the sound alone, Kirst knew it was nothing edible. He brought it up to his mouth anyway and tasted it, bit into it. He spat grit. It was rock.

Before he could grasp another box, the crate was hit by a wave. Seawater showered through the opening, and Kirst swallowed enough to burn his throat. He coughed and tried to hack it up, but the bitter taste remained in his mouth. He began to realize that without fresh water or food, his strange little craft would become his coffin.

He raised his hips and dug deeper, hoping desperately to find something edible. He pulled up six packages. Five were duplicates of the first, containing the same sort of flat, worn stone tablets. With mounting frustration, Kirst pitched each of them overboard.

The sixth was different. The box was square. He could feel a wooden frame under heavy paper sealed with wax. He tore at the paper and tried to pry the wood loose, but all parts of the box had been carefully glued shut. Someone had taken extra trouble with this one. Kirst shook it and heard from inside the reassuring gurgle of liquid.

Hope swelled in his brain. His stomach dictated every move he made thereafter. He sat up and stuck his head out of the crate. He grabbed the knife he had left embedded in the wood.

Shaking with anticipation and hunger, Kirst pried the glue apart and struggled to separate the lid from the box. The glue was old and dry and he heard it crack, then the box popped apart in his hands.

Something heavy fell into his lap. It caught the starlight from above and gleamed brightly. Kirst stared at it. It was some sort of flask or bottle, made of metal, with a smooth surface, warm to the touch. He held it up to the stars to see it better. It was five-sided, with a broad base tapering up to a narrow neck. The stopper was sealed to the neck with wire. Both the stopper and the flask, he realized, were made of pure silver. Kirst shook it. Again it gurgled.

Kirst laughed happily. Wine. Probably a very rare vintage. If he was to die out here, at least he would go in style.

Using the knife, he worked the wire loose and unwound it. He turned the stopper and was surprised to find that it came out easily. He dropped it in his lap and brought the open flask up to his nose, hoping to smell the pungent aroma of a

grand cru

burgundy, but nothing so wonderful teased his senses. There was no bouquet at all.

With a softly muttered “Heil,” he brought the flask to his lips and drank greedily.

A warmth that Kirst hadn’t felt in hours shot through his body. The liquid had a sour taste, not winelike at all, almost medicinal and very oily. It infused him with a sense of well-being. He arched his head back and swallowed the last of it.

Gagging on the bitter residue at the bottom, he leaned over the side of his makeshift boat and spat it into the sea.

As it struck the ocean, it sizzled and burst into flame.

Kirst watched it, amazed, briefly wondering whether he had poisoned himself.

Thoughts trailed away as the warmth moved inside him and helped him relax. A moment later, without knowing why, Kirst threw the empty flask as far away as he could. He watched it bob a moment, then saw it fill with water and sink from sight.

PART ONE

Chapter 1

Ishtar was the Babylonian goddess of love, worshiped by the largest cult of followers in ancient Mesopotamia. Loring Holloway turned the tiny carved image over and over in her hands, feeling the rough stone and delicate indentations beneath the pendulous breasts.

As much a goddess of war as of love, to the Phoenicians she was Astarte, to the Semites, Ashtoreth, and to the Sumerians, Inanna. But to the Babylonians she was chiefly an excuse for orgies of wild abandon and ritual prostitution.

To Loring Holloway she was exhibit number G814 in the new Mesopotamian display. She would have a place of honor in a glass case, lit from two sides and fixed upright on a pedestal covered in red satin,

if

Loring could get red satin somewhere during these wartime shortages, and

if

there was enough in the budget to purchase it on the black market should that become necessary. Otherwise, little Ishtar would be resting on colored construction paper.

Loring leaned back in her creaking swivel stool. The light was bad down in the basement of the Metropolitan Museum. They were saving on electricity, too. She looked over at the stack of opened crates that were her responsibility. So much work left to do for a display date seven months away—she doubted she would make it without assistance. There wasn’t even a secretary to handle the cataloging: she had to do it all herself—unpack the artifacts, check the master inventory and the descriptions, be sure there were no new defects, measure with calipers, draw a rendering as faithfully as possible, and write the museum catalog description that would eventually go to the printer. Then she had to decide where and how everything would be displayed, and write it all down so that the museum custodians would make no mistakes.

She groaned and rolled her shoulders. Her back ached. She had asked for a straight-backed chair three weeks ago. She couldn’t believe that

chairs

were hard to find in wartime.

She thought back on the career she had dropped for the duration. Field archaeology was far more rewarding than museum staff work. But where Loring wanted to be, where she felt she belonged, was too dangerous at this time. The Middle East, though not the focal point of the war, was nevertheless embroiled in it.

Loring heard the elevator creaking and clanking. The doors opened with a series of crashes. She stared down the long dark basement corridor, past stacks of crates that belonged to other displays. Footsteps clacked on ancient linoleum, and a figure was silhouetted coming up the corridor and into the light.

“Hiya, honey.”

His face appeared under the first conical work light. He took off his hat and kept coming, shrugging out of his coat. It was Warren Clark.