Blood and Belonging (33 page)

Read Blood and Belonging Online

Authors: Michael Ignatieff

Tags: #Political Ideologies, #Social Science, #General, #Political Science, #Ethnic Studies, #Nationalism, #History

CHAPTER 6

NORTHERN IRELAND

MIRROR, MIRROR

The shutters are run down on the butcher shops and the betting shops, and crowds gather silently on the pavements. In the distance, from the tight warren of streets off the Shankill Road, comes the skirl of pipes and the tread of feet. A flatbed truck appears first, bearing wreaths with the initials of the Ulster Volunteer Force picked out in red, white, and blue flowers; then comes a hearse with a flower-decked coffin, followed by a silent army of men. There are perhaps two hundred of them, wearing big-shouldered, double-breasted suits, white shirts, black ties. Their dark glasses glint as they turn to scan the crowd. When they see a camera, a posse breaks ranks and comes over to pass the word. “Now, don't be filming. Wouldn't be wise.”

The Shankill is paying its last respects to Herbie McCallum. He had been providing protection for a Protestant parade, armed with a pistol and a grenade, when the police tried to reroute the march away from the Catholic Ardoyne. Scuffles broke out between Loyalists and the police. Some say the grenade was intended for the Catholics, others for the police, but the person who took the full force of the explosion was twenty-nine-year-old Brian “Herbie” McCallum, father of two, paramilitary hero to his friends, Protestant terrorist to his enemies.

Before the rifles were fired into the air in the graveside salute, one of Herbie McCallum's commanders gave a speech in which he said:

To stand for capitulation. To stand silent, immobile in the face of treachery. To suffer ignominiously the malignment of our people, our culture, our history. To bow to the whims of mere pragmatistsâis cowardice. Volunteer Brian Herbie McCallum and many many Ulster Volunteers who have made the ultimate sacrifice are testimony that this Nation will be defended.

L

ATER THE SAME AFTERNOON,

I am driving down Antrim Road, thinking how much it looks like my own street in north London. There are the same brick terraced houses lining both sides, with trimmed box hedges and rose bushes nestling beneath the bay windows. Everything is British and familiar, so what is this bus doing ablaze in the middle of the

road? I am about thirty feet away, getting out of my car, and ahead of me a fireman is running toward the fire when an explosion throws him onto his back. When I look up again, the fireman is struggling to his feet and the bus is burning more fiercely than ever.

I've driven into a Belfast bus-hijacking. A minute before I arrived, a man with a gun had stepped out onto the road, ordered the driver and passengers off, and then lobbed in a petrol bomb. Chances are the gunman may be watching, waiting to ambush the police. Armored gray Land Rovers have already blocked off the road. Officers in flak jackets have taken up position behind walls. Judging from the fact that the street leads up from the Shankill, the gunman is a Loyalist.

Children quickly gather to splash around the hydrants while mothers stand out on the front steps in their aprons to watch the bus burn down to its frame. A woman comes over and says, “You mustn't think this is how it is all the time. This is a great wee city. Don't get the wrong idea.”

I try not to get the wrong idea, but in the course of the next three hours, I come across two more hijackings, delivery vans left smoldering in the middle of residential streets, while police marksmen cover them from suburban gardens. Over the normal sounds of a British city at night, I can hear the pop and crack of automatic-weapons fire.

The two days after Herbie McCallum's funeral see the most extensive Loyalist rioting in Belfast in a decade. Forty buses and cars are hijacked and burned; there are twenty-eight gun attacks on the police and nine firebombings; when fire engines arrive in the Donegall Road area to put the burning cars out, the fire engine itself is hijacked, the crew thrown off it, and the tender set alight. Police called into the

Rathcoole, Woodvale, Shankill, Highfield, and Tiger's Bay districts are fired upon. The police believe the rioting is a show of force, planned by those two hundred silent young men in dark glasses walking down the Shankill behind Herbie McCallum's coffin.

U

LSTER IS A GOOD PLACE

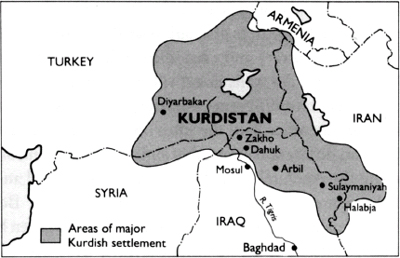

to end my journey, because it seems to reprise so much of what I've already seen on my travels: paramilitaries as in Serbian Krajina and Kurdistan; ethnic paranoia as in Croatia; the cult of male violence as in German skinhead gangs; a national security state as in Turkey. The helicopters constantly drone overhead, the Land Rovers and armored personnel carriers squat astride every major junction, and men in helmets stare at you down their gunsights.

Like most outsiders, I'd dismissed the Troubles as a throwback to the tribal past. Now, in 1993, Northern Ireland seems like a possible future writ large. No place in Europe has carried ethnic division as far as Belfast. The peace walls, put up in the 1970s to keep people in the same street from firebombing and murdering each other, are now as permanent as the borders between nation-states, twenty feet high in some places, sawing working-class Belfast in two.

Ethnic apartheid does reduce the death toll. In the mid-1970s, between 250 and 450 people were dying every year. Now the figure is under 100. At the same time, community segregation is growing. Sixty percent of the population now live in areas that are more than 90 percent Protestant or Catholic.

The segregation grows in molecular fashion: a tire is slashed, a child is beaten up, petrol is poured through a letter box, by one side or the other, and another family decides to choose the safety of numbers. Belfast likes to talk about

“ethnic cleansing”âbut molecular nastiness bears no comparison to genocide in Bosnia. If Sarajevo could look like Belfast one day, it would consider itself lucky.

In Northern Ireland, as in Croatia and Serbia, as in Ukraine, ethnicity, religion, and politics are soldered together into identities so total that it takes a defiant individual to escape their clutches. On one side, people who have never been to a church in their lives have to live with the tag of “Protestant.” On the other, people who have no desire for a united Ireland but happen to be Catholic get labeled, once and for all, as “nationalists.”

These labels imprison everyone in the fiction of an irreducible ethnic identity. Yet Northern Ireland's is not an ethnic war, any more than the Serb-Croat or Ukrainian-Russian antagonisms are ethnic. In all three cases, essentially similar peoples, speaking the same or related languages, sharing the same form of life, differing in religions which few actually seem to practice, have been divided by the single fact that one has ruled over the other. It is the memory of domination in time past, or fear of domination in time future, not difference itself, which has turned conflict into an unbreakable downward spiral of political violence.

I am in Ulster to find out what Britishness looks and feels like when it has been put on the rack of a dirty war. In mainland Britain, Britishness is a casual puzzle, a subject for after-dinner conversation. In Ulster, it can be a matter of life and death. Loyalism, I thought, would serve as a mirror that would show me what the British might look like if their nation's life was on the line. I've chosen to visit in July because the great festival of Loyalism, the marching season, is about to begin. But after Herbie McCallum's funeral I'm already unsure as to what the mirror of Loyalism reveals.

Protestant paramilitaries now kill more people in Northern Ireland than the IRA. Their victims range from innocent Catholics to British soldiers and members of the police. Here is a Britishness at war with Britain, a Britishness that swears allegiance to the Crown and the Armalite rifle.

T

HE ILLUSION

that Britain is an island of stability in a world of troubles does not survive a day on the streets of Belfast. In reality, there is more death by political violence in Great Britain than in any other liberal democracy in the world. Since 1969 there have been three thousand political killings and more than fifty thousand people have been seriously injured. More people have died, per capita, of political violence in Great Britain than in India, Nigeria, Israel, Sri Lanka, or Argentina, all nations which the British regard as more violent than their own.

There is nothing especially mysterious about this level and intensity of violence. Nationalism by its very nature defines struggles between peoples as struggles for their honor, identity, and soul. When the stakes are raised this high, conflict is soon reduced to a zero-sum game. Victory for one side must mean total defeat for the other. When the stakes appear to involve survival itself, the result is violence. Such is the case in Northern Ireland. Two nation-states lay claim to the province. Nine hundred thousand Protestants or descendants of Protestants wish to remain British. Six hundred thousand Catholics or descendants of Catholics mostly, but not invariably, wish to become Irish. Since one wish can be satisfied only at the expense of the other, it is scarcely surprising that the result is unending conflict.

What is more surprising than the level of violence is the willingness of the mainland to continue to pay the price.

A relatively poor liberal democracy spends £3 billion a year and deploys twenty thousand troops to back up a local police force in a struggle which can be contained but which cannot be won.

Such commitment would be unthinkable if the territorial integrity of the British state and the legitimacy of its authority were not both on the line. One might have expected that such a cause would rouse the deepest nationalist feeling. Yet all that seems to sustain the British presence is a weary cross-party consensus that terror must not be seen to pay and that the troops cannot be withdrawn lest civil war ensue.

If the cause in question in Northern Ireland is defense of the Union, then already Ulster is not treated like a part of mainland Britain. There is an imperial proconsul, the Northern Ireland Secretary, who runs everything from negotiations with Dublin to the allocation of council housing. The currency is the British pound, but the Northern Ireland banknotes are not tradable as legal tender on the mainland; British political parties do not compete for votes in the province. Local democracy has been all but eliminated by twenty-five years of direct rule from Westminster. Ulster knows it is already semidetached.

Loyalists bitterly note the curious disparity between the outpouring of nationalist feeling when Argentina invaded “British sovereign territory” in the Falklands and the indifference about Ulster. Mainland Britain would give Ulster away if it could. Opinion polls give greatest support to options that entail relinquishing British sovereignty over Northern Ireland or sharing it with Ireland.

And the British commitment to Ulster is hedged with conditions. Since the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985, Britain is committed to remain in Northern Ireland only so long as

a majority of its people wish it. Thus the province is the only part of the Union with an entrenched right of secession. For Loyalists, it is an outrage that the British government should portray itself increasingly as a “neutral” peacekeeper between one community which wishes to stay British and another which wishes to become Irish.

If the cause in question in Ulster is the defense of the Union, then it is a cause that moves few British hearts. Yet this is paradoxical. British nationalism has always been of the civic variety: an attachment to the institutions of a stateâ Crown, Parliament, rule of law, the Union itselfârather than to a nation. Yet like Canada, India, Belgium, and other multi-ethnic states, it is discovering that attachment to the state may prove weaker than commitment to the nations that comprise it. The Union, after all, is a constitutional contrivance, and who can feel deep emotion about constitutional contrivances?

Ethnic nationalism attaches itself to the defense of a tradition and way of life, and all of this could survive a redrawing of the Union. The British could cede Northern Ireland and few on the mainland would feel the sting of shame or the twist of remorse. Whether they should do so is another matter. But what exactly does this tell us about Britainâthat it has lost the nationalist impulses which might once have rallied to Ulster's defense, or that it never had them in the first place?

T

HE ENGLISH HAVE

always made the comparison between their own tolerant moderation and the nationalist delusions of other peoples a touchstone of their identity. Living on an island, having exercised imperial authority over more excitable peoples, priding themselves on possessing the oldest continuous nation-state in existence, the English have

a sense of a unique dispensation from nationalist fervor. An ironic, self-deprecating national character that still prizes the emotional reserve of its officer class approves of itself for declining the strong drink of nationalist passion.

Hugh Seton-Watson, a great English historian of Eastern European nationalism, was convinced that there was no such beast on his own soil. A people who have never been conquered, invaded, or ruled by others, he believed, could not be nationalistic. “English nationalism never existed, since there was no need for either a doctrine or an independence struggle.” A Scottish nationalism perhaps, a Welsh nationalism, too, but never an English nationalism.