Blood and Salt (29 page)

Authors: Barbara Sapergia

Tags: #language, #Ukrainian, #saga, #Canada, #Manitoba, #internment camp, #war, #historical fiction, #prejudice, #racism, #storytelling, #horses

Mrs. Shawcross smiles at her. “Helena, this is my son, Ronald.”

“How do you do, Mr. Shawcross.” Halya makes the small gesture between a nod and a bow that Louisa’s taught her. “Dinner is ready, madam.” Louisa has been drilling her in these phrases for several days now.

“Thank you, Helena. Please set another place for my son.”

“Helena...” Ronnie says. “Not a Galician name, I would have thought?”

“In my language, I am Halya.” She turns and goes to the kitchen. She can still hear them as she carries roast lamb and vegetables to the dining room.

“You never mentioned she was beautiful,” Ronnie says.

Oh shut up, Halya thinks. Stupid calf.

And then the

pahna’s

voice. “You’re to keep away from her. Do you understand?”

“Mother, what on earth are you on about?”

“And what brings you here tonight? I really wasn’t expecting you.” Halya has never heard any mother talk to her grown son this way. She wishes she could catch all the words.

“It’s that pack of coyotes, Mother. They killed a couple of my lambs.”

“Our

lambs, Ronnie.” Halya misses the rest, but they’re arguing –

something about his father’s death and Ronnie running the brick plant.

“Mother!” she hears Ronnie say. “I hadn’t realized you had such a poor opinion of my abilities.”

“That is because you don’t pay attention,” Mrs. Shawcross says in a nasty tone.

Ronnie’s face turns an ugly purple. Halya thinks he’d like to strangle his mother.

Mrs. Shawcross notices Halya in the doorway. Halya steps forward.

“Dinner is on the table, Mrs. Shawcross.” Another of Louisa’s little phrases.

“Thank you, dear. Ronnie, will you give me your arm?”

Ronnie lets the question hang, looking at Halya’s face – no, gaping – slowly forgetting his anger.

Have you never seen a woman before? Halya wonders.

Finally he offers his mother his arm and leads her into the dining room.

CHAPTER 18

Conspirators

March, 1916

A small party

cuts firewood. The temperature is well below

zero, but it doesn’t feel as cold as it would’ve in January. The sky is drenched in sun. Ice crystals reflect minute flashes of light. Impossible not to feel that winter’s back is broken. Sergeant Lake calls the lunch break and the men scatter to log and rock perches. Taras and the carver happen to sit near Lake in a sheltered

corner of the clearing.

They see a black, weasel-like creature high in a tree. It leaps to the next tree. Its long tail works like a sail in the sparkling air.

“What’s that?” Bohdan asks.

Taras sees he’d like to make a carving of this animal.

“Pine marten,”

Arthur Lake says. “Almost looks too large to be so agile, doesn’t it? Moves like a squirrel. Eats them, too.” The marten pounces on some small animal and begins tearing it apart.

Taras raises his arm to take a bite of his sandwich. He hears a sudden squawk, sees a blur of claws and feathers, and the sandwich is no longer there. Until it disappeared, Taras had considered the sandwich barely edible, but now it seems like something precious. Lake can’t help laughing.

“What the hell’s that?” Taras glares at a handsome grey bird high up on a branch, pecking at the icy blob.

“Whiskey-jack. Also known as a grey jay.”

“Grey thief.” Taras picks up a spruce cone and flings it at the bird, but it falls short. The bird doesn’t shift a feather. He has to laugh.

Bohdan gets up to watch the bird more closely. Follows it as it hops to another tree.

“Look, I’ve got something I was saving until I was desperate.” Lake pulls out a thick slice of frozen fruitcake, takes a jackknife from his pocket, cuts the cake in two and hands one half to Taras. “My wife made it.”

“Dyakuyiu.”

He takes an icy bite and sweetness fills his mouth. Seeing Lake’s knife, Taras decides to tell him about Bohdan and his carvings; how his knife has been taken away.

After a moment’s thought, Lake hands over the knife. “You give him this. I’ll come and see his carvings some time.”

Taras puts the knife away in his pocket. No one has seen.

“Dobre.

I’ll give it to him.” He bites off another chunk of cake and warms it in his mouth, tastes raisins and dates and chopped apricots.

Smachniy.

Taras has cleared brush at the buffalo paddock under this man’s direction and cut trees for roadbeds and fuel. Of all the guards, only this one gives you room to breathe. Only this one seems interested in where he is.

He’s learned to refer to the prisoners as Ukrainians.

The marten appears in a much closer tree. Stares at the humans as if he’s trying to work out what they’re doing there and how this can benefit him.

“He’s like us,” Arthur Lake says. “Has to find something to eat.”

“Working in an internment camp is a damn hard way to find something to eat.”

“Bloody hard,” Lake agrees. “We’re sitting here freezing while the pine marten stays warm and eats fresh meat.”

“And the grey bird steals our food.” The whiskey-jack still pecks away at the bit of sandwich. “I guess he’ll know better next time.”

The break is done. They pull themelves up to get on with the work.

The temperature creeps

above freezing and the men unfasten their mackinaws. By mid-afternoon, Sergeant Lake tells them to stop – they’ve felled and trimmed as many trees as they can carry.

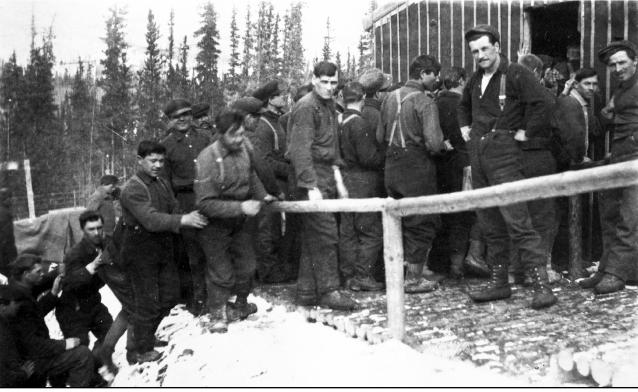

They take the logs back to camp, cut them to fit in the stoves, stack them in the bunkhouses. They line up early at the mess hall, some of them without coats.

Sergeant Lake sets up his camera as the internees climb the steps to go inside. Only a few men notice him. At the last moment, a man called

Yars sees him and turns, hands on hips, to the camera. His face, his posture say, “What the hell do you think you’re looking at?”

Arthur Lake takes the picture.

Back in the bunkhouse,

Yuriy pulls a small sack of potatoes out of his coat and hides them under his bunk. He tells his friends what they’ll be buying next time they go to the canteen. Cigarettes and more cigarettes.

To pay for the potatoes. He’s been collecting them for several days. Also sugar, and raisins.

They look at each other.

This can mean only thing.

They borrow Bohdan and his new knife to peel the potatoes.

They borrow Taras’s extra shirt, recently washed.

They borrow a clean handkerchief from Myro.

Yuriy has noticed a closet in the prisoners’ laundry shack. It contains an old galvanized boiler, leaky if you fill it too full, but usable. No one bothers with it since a new one was bought. To clean their clothes, people heat water on the wood stove and pour it into round wooden washtubs where they rub their garments on scrubbing

boards. Then of course they need to rinse them. The whole process takes a fair bit of time.

This means that no one should get too suspicious of how long it’s going to take Taras and his friends.

They begin early on Sunday. Six men – Yuriy, Taras, Tymko, Myroslav, Ihor and Bohdan take over the small room. Myro keeps watch at the door. They clean the boiler, set water to boil and begin peeling potatoes.

That is, Bohdan peels potatoes. He doesn’t like other people using his knife. Once a little guy called Big Petro took Bohdan’s old knife without asking – to cut his toenails. Big Petro’s toenails were thick and yellow, like hooves. Of course the knife slipped. It took hours to stop the bleeding.

After the potatoes are peeled and rinsed, Bohdan chops them up and puts them in the boiler with lots of water. Yuriy simmers them on the stove for twenty minutes or so and then takes off the scum with the clean hankie. He adds the sugar and raisins and a small package of yeast and cooks the whole mixture a little longer. They let it cool a bit and carry the boiler to the closet.

“It’s going to smell,”

Tymko says.

Bohdan pokes out a couple of knotholes in the outer wall. “That’ll help.

Anyway, people bring in smelly laundry.

Who’s going to notice?”

Myro has to fend off a couple of men who want to wash their clothes.

Taras’s shirt makes a good cover to keep dirt out of the boiler while allowing the fermentation gases to get out.

The conspirators shut the closet door firmly. Pails of water are hot now, in the new boiler, for their own laundry.

CHAPTER 19

Where is Halya?

Every day

brings a little more sun. Taras feels a pool of warmth inside him, as if the light shines through to his bones.

His friends want more story, but what they most want to know he can’t tell them: Where is Halya? He agrees to talk about his time at the school building site, but soon he’d like to stop. He hopes when it’s warmer they’ll forget all about it.

He’s in charge

of the horses now. His favourites are Charlie and Bessie, lead horses for the four-horse team. They’re so smart, they follow his signals almost before he gives them. At the end of the day he drives the team to the livery stable. He curry combs all four and brushes dirt out of the long feathering over their feet. The time he spends with them is a gift.

He’s also a decent bricklayer now. One day he’s working on a wall when Dan Stover shows up. He comes every two weeks to pay the men their wages, but today the boss is with him. Shawcross walks around the foundation, observing the progress with the air of a

pahn

back in Bukovyna.

Out of sight of the boss, Stover jabs Taras’s arm. “War’s coming, hunkie. Saw it in the paper.

You wait, they’ll send you foreigners back where you belong.”

“Get lost, Stover.

”

This is Frank Elder, one of the best workers at the site. “Only people who aren’t foreigners here are the Indians.”

“That’s garbage.

This is our country. An English country.”

“I imagine the Indians wish we’d all go back where we belong.” Elder winks at Taras. “You especially.”

“Shut your face. Hunkie lover.” Stover swaggers off, trying to act like he doesn’t care what Elder said, but he does. People respect Elder. It’s the end of July payday. They all gather near the wagon. Shawcross calls each man’s name and hands him a pay packet.

He goes down the list of men who have worked there a long time. The foreman, Rudy Brandt, Frank Elder, Jimmy Burns, Arlen Sundstrom, Johnny St. Hilaire, and several others. Taras is always last.

“Taras Kalyna,” Shawcross says finally. He pronounces it “Ka-

leen

-uh.” Taras takes the envelope and counts his money. Shawcross climbs into the wagon without looking back. As he and Stover drive off

,

Jimmy Burns, a stocky man in his twenties, stares after them.

“Lord of the bloody manor. Hands us our pay like he’s doing us a favour.”

“You’re complaining? I haven’t had a raise in ten years. Not since old man Shawcross died.” Frank rubs his hand over the back of his neck, aching from unloading and laying bricks. He’s a wiry little guy with foxy red-gold hair. Even in his fifties Frank gets more done than most young guys. He knows how to move. Doesn’t waste energy.

“I’ve lost count how many of little Ronnie’s damned buildings I’ve worked on,” Frank says. “But he never understands why we’re important. Not like the old man. He had more sense in his little finger –”

“Isn’t it time we did something about it?” Rudy Brandt asks. Rudy’s also in his fifties. Grey hair grows at his temples and in his beard. He’s grown a little stooped working on what Frank calls “Ronnie’s damned buildings,” and must be wondering how long he can keep working.

“Maybe we can do something,” Frank says. “We can talk.”

Taras can see that Elder’s waiting for him to move off before saying anything else, so he goes back to laying brick. But he’s curious. What can they do?

Taras gets up

and walks around the bunkhouse.

This part of the story makes him bitter and he’s a little tired of trying to entertain his friends. He doesn’t hear any of them telling

their

lives to pass the time.