Blood Brotherhoods (29 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

After the post-mortem, investigations into the picciotteria in Africo finally began to make real progress. More

Carabinieri

arrived in the village, and were billeted in a house right next door to Domenico Callea’s. The picciotteria’s bookkeeper and fencing instructor had gone on the run after ordering Pietro Maviglia killed. His new wife was left alone in the house. She kept the

Carabinieri

awake all night with the sound of her sobbing.

The strong military presence in Africo encouraged more witnesses to come forward. With Sergeant Labella’s energetic help the magistrates preparing the prosecution case were able to tease out more and more evidence. Maviglia’s murderers were arrested. Under interrogation, they broke: blaming one another at first, and then finally confessing. In the Grecanico-speaking communities, the wall of

omertà

around the picciotteria collapsed.

Perhaps the most historically significant truth to surface after Maviglia’s brutal demise was that the criminal network that the Lads with Attitude rapidly created in the 1880s and 1890s had an enthralling religious symbol at its centre.

The Sanctuary of the Madonna of Polsi lies hidden in a valley in Aspromonte’s upper reaches. Legend has it that in 1144 a shepherd came to this secluded spot looking for a lost bullock. He was greeted by a miraculous vision of the Blessed Virgin. ‘I want a church erected’, she declared, ‘to spread my graces among the devout who will come here to visit me’. For centuries, in early September, poor pilgrims have made their way up the twisting mountain roads to Polsi in joyous conformity with the Virgin’s wishes.

Calabria’s greatest writer, Corrado Alvaro, described Polsi as it would have been in the late nineteenth century, when twenty thousand men and women flooded the churchyard and the woods round about in preparation for the Festival. Some had walked barefoot all the way; others came wearing crowns of thorns. The men drank heavily and fired their guns in the air. Everyone feasted on roast goat, bellowed ancient hymns, and danced all night to the music of the bagpipe and the tambourine.

On the day of the Festival itself, the tiny church was filled with the imploring wails of the faithful, and with the bleating and mooing of the animals brought as votive offerings. Hysterical women shrieked vows as they elbowed their way through the crowd to place eerie

ex-votos

at the Madonna’s feet: brass jewellery, clothes, or babies’ body parts modelled from wax. When evening came and the Madonna was paraded around the sanctuary on a bier, the pilgrims prayed, wept, beat their chests, and cried out ‘viva Maria!’

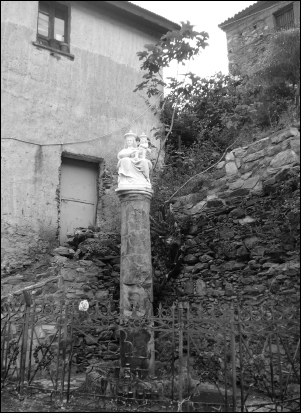

The Sanctuary of the Madonna of Polsi, on Aspromonte. Since at least 1894, the ’ndrangheta’s annual gathering has coincided with the Festival of the Madonna of the Mountain held here.

The Festival of the Madonna of Polsi has a special symbolic significance for the ’ndrangheta. To this day the Chief Cudgels from across the province of Reggio Calabria use the Festival as cover for an annual meeting. In September 2009, prosecutors maintain, the newly elected ‘Chief of the Crime’, Domenico Oppedisano, came to have his appointment ratified at Polsi. Senior positions in the ’ndrangheta’s coordinating body, the Crime, come into force at midnight on the day of the Festival.

The nearest town to the Sanctuary at Polsi is San Luca, where the writer Corrado Alvaro grew up, and where the

’ndrine

(local mafia cells) involved in the Duisburg massacre of 2007 originated.

’Ndranghetisti

refer to San Luca as their Mamma; the ’ndrangheta there is traditionally the guardian of the whole association’s rules, and the arbiter in disputes. San Luca has been called the ‘Bethlehem’ of Calabrian organised crime.

We can now be sure that the Polsi crime summit is a tradition as old as the ’ndrangheta itself. For in June 1895 a shopkeeper from Roccaforte del Greco told the magistrates investigating Pietro Maviglia’s murder what he had seen in Polsi.

On 3 September 1894 I went to the Festival of the Madonna of the Mountain. There I saw several members of the criminal association from Roccaforte in the company of about sixty people from various villages who were all sitting in a circle eating and drinking. When I asked who paid for all that food and wine at the Festival, I was told that they paid for it with the camorra they collected.

Evidently the pilgrimage to the Sanctuary at Polsi was, from the outset, a chance for the Lads to make a profit and talk shop rather than to worship.

Sergeant Labella’s investigations also threw up more scattered evidence about how the picciotteria began. Although he could not be precise about the year of its emergence, he thought that it was no later than 1887, the year that the sect’s ‘judge’, Andrea Angelone, was released from prison. Other witnesses pushed the starting date back further. One resident of the same village said he thought Angelone had been a member of a criminal association ‘sixteen or seventeen years back’ (i.e., in about 1879).

The elementary-schoolteacher in Africo proved to be a particularly insightful witness. He had first taken up his post in the mid-1880s and had immediately heard talk of a criminal sect in town. But ‘this association, it was said at the time, comprised three or four people’. Its numbers increased rapidly over the coming years, particularly during Domenico Callea’s recruitment drive in 1893–94.

The story that these fragments of evidence tell—a story that was being repeated in Palmi, and indeed all around Aspromonte—goes something like this. Until the mid-1880s, a few Calabrian ex-cons, the senior

camorristi

from within the prison system, would keep in touch when they returned home from jail. They might offer one another help and even get together for the odd criminal venture: the trial records and other sources tell us of occasional outbreaks of gang activity in various parts of the province of Reggio Calabria in the 1870s and even before. But the

picciotti

as yet lacked the numbers and the strength to impose themselves on other felons in the outside world in the way that they had done in the confined environment of prison. Needless to say, they also lacked the power to browbeat whole towns. Then in the 1880s there were changes that gave Calabria’s prison camorra the chance to project itself into the outside world. The question, of course, is what exactly those changes were.

It is telling that no representative of the state seemed at all curious to answer that question. In 1891, Palmi’s Chief Prosecutor wrote his annual report on the work of the court during the previous year. The picciotteria did not even merit a mention: it was only a superficial symptom of Calabria’s chronic backwardness, after all. The reason for the high rate of violence in

the Palmi district was not organised crime, he wrote, but the ‘ardent and lively nature of this population, their touchiness, the stubborn way they stick to their plans, the unwavering tenacity of their feelings of hatred—which very often drive them to vendetta’.

If a Sicilian Chief Prosecutor had written such claptrap we would have very good reason to be suspicious of his motives. But in Calabria, such suspicions are probably not merited. (Not yet, at any rate.) After all, the Palmi court had just sent dozens of

picciotti

back to jail. But the Chief Prosecutor’s stereotypical views of the Calabrian psyche are significant all the same. Railway or no railway, Calabria was still seen as a semi-barbaric, faraway land about which Italy knew very little and cared even less. Despite its ties to the international market for olive oil, wine and lemons, Palmi was simply not important enough to draw much government curiosity down on the picciotteria, which means that historians have to work harder to solve some outstanding mysteries about its emergence.

Sworn sects have dominated prisons in many different times and places. The long-established South African number gangs, the 26s, the 27s, and the 28s, for example, who take their mythology from the story of a Zulu chief. Or the vast network of

vory-v-zakone

(‘thieves with a code of honour’) who infested the Soviet Gulag system from the 1920s. The

vory

had a ‘crowning’ ritual for new members, sported tattoos, and had a distinctive look comprising an aluminium cross round the neck and several waistcoats.

But by no means do all of these gangs manage to establish their authority in the world outside the prison gates. The 26s, the 27s, and the 28s only did it in the 1990s, when Apartheid fell and the country was opened to narcotics traffickers who needed local manpower and a local criminal ‘brand’. When the Soviet Union collapsed the

vory-v-zakone

did not simply step out of the Gulag to assume leadership of the crime bonanza that ensued. Rather they had their traditions hijacked by a new breed of gangster bosses who wanted to add an air of antiquity to their territorially based bands: the result was the Russian mafia. Examples like these show just what an achievement it was for Calabria’s prison

camorristi

to carve up territory in the outside world between themselves.

The economy is surely a big part of the reason why they pulled it off. An economic crisis hit Calabrian agriculture with increasing force in the 1880s. Phylloxera reached Italy and the wine boom went sour. Then a trade war with France threw agricultural exports into crisis. Some smallholders, like those in the Plain of Gioia Tauro, had run up debts to buy a plot of former Church land and plant it with vines: they now faced penury. Others had bullied or bribed their way to ownership, and now faced the wrath of their

factional enemies. Meanwhile, the poorest labourers, like those in Africo, struggled even harder to feed themselves. There were plenty of recruits for the picciotteria, and plenty of landowners and peasants vulnerable or unscrupulous enough to consider striking a deal with the men of violence.

The arrival of the steam train was also partly to blame, in Palmi at least. Contemporaries noted that the initial upsurge of razor attacks and knife fights coincided with the presence of navvies working on the Tyrrhenian branch of the railway in the spring of 1888. A dozen years later, in around 1900, some observers began to claim that the Lads with Attitude had been

imported

into the Plain of Gioia Tauro by Sicilian

mafiosi

among the navvies. But since none of the men convicted in Palmi’s court house were Sicilians, this theory is almost certainly wrong. A more likely scenario is that there were ex-con

camorristi

among the railway workers. The fighting in Palmi could have been the result of competition for jobs with local

picciotti

.

Either way, the role that the railways played in the emergence of the Calabrian mafia makes for a bitter historical irony. As one magistrate opined at the time

Whether the railway brought more evil than advantage is unclear. It is painful to ascertain that such a powerful influence for civilisation and progress served to trigger the cause of so much social ignominy.

The ’ndrangheta began just when Calabria’s isolation ended.

There is a third likely reason why the picciotteria appeared when they did. In my view, it is the most important. In 1882 and 1888 two important electoral reforms inaugurated the era of mass politics in Italy. The number of people entitled to vote increased. Local government obtained both more freedom from central control, more responsibilities for things like schooling and supervising charities, and with them, more resources to plunder. With around one quarter of adult males now entitled to have a say in who governed them, politics became a more expensive and more lucrative business.

More violent too. Shootings, stabbings and beatings had always been part of the language of Italian politics, particularly in the south. Much of the violence was administered from Rome. On orders from the local Prefect, the police would rough up opposition supporters, arrest them or simply take away their gun licences, leaving them vulnerable to attack by goons who worked for the candidate the government wanted to win. The reforms of the 1880s greatly increased the demand for violence at election times and encouraged more aspiring power brokers to enlist support from organised enforcers.

Strong-arm politics was not something that the police were particularly keen to investigate, understandably enough. But there are nonetheless clear signs from deep within the dusty folders of trial papers that even in Africo the picciotteria had friends among the elite. The press remarked that the men who sliced up the crippled old swineherd Maviglia were defended by the best lawyers in Reggio Calabria. And among the

picciotti

in the case were ‘people who, because of their prosperous financial state, can only have been driven to crime because they are innately wicked’.

The ‘innately wicked’ inhabitants of Africo included the former mayor, Giuseppe Callea, whose sons were prominent

picciotti

: Domenico, the sect’s bookkeeper and fencing instructor who tried to recruit the bagpiper into the gang; and his brother Bruno, the

picciotto

who was sent to prison for robbery on the evidence provided by the crippled swineherd Pietro Maviglia. Former mayor Callea clearly endorsed his sons’ criminal career path: he himself physically threatened Maviglia.