Blood Brotherhoods (41 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

The stool pigeon who destroyed the camorra: a dapper Gennaro Abbatemaggio gives evidence from the cage built to protect him from his former comrades, 1911.

‘The camorra is a career’, he began in an attractive baritone, ‘which goes from the rank of

picciotto

to that of

camorrista

, passing through intermediate ranks.’ He joined the camorra in 1899, at age sixteen, as a

picciotto

. In 1903 he was promoted to the rank of

camorrista

in the Stella section of the Honoured Society.

Camorristi

in Naples exploit prostitution greedily . . . They demand a

camorra

[a bribe] on everything, and especially on all the shady activities that, precisely because they are illegal, have to pay the camorra’s tax. They extort the

camorra

on illegal betting, on the gambling dens that cover Naples like a rash. They extort the

camorra

on sales at public auctions, and even show their arrogance during national and local elections . . . The camorra is so base that it takes money, sometimes even really tiny payments, to massacre or disfigure people. The camorra is involved in loan sharking. In fact its biggest influence is on loan sharking.

Abbatemaggio went on to describe the camorra as ‘a kind of low-grade Freemasonry’. His description of the camorra’s rules, structure and methods confirmed the criminological ‘textbooks’ that had been so popular in Naples for years. He ended with a passionate plea.

My assertions are the absolute truth. I want to carry my head high, and look anyone who might dare to doubt them straight in the face.

Abbatemaggio then began to reel off his account of how the Cuocolos came to be so brutally slain on that June night nearly five years previously.

The letters from the Lampedusa penal colony. The lobbying by Johnny the Teacher and the Cowherd to have Gennaro Cuocolo punished. How the plenary meeting of the camorra’s top brass at the Bagnoli trattoria approved the decision. How Big ’Enry organised the executions in a series of meetings in the Galleria. The savage actions of the two teams of killers. The dinner at Mimì a Mare. The story of Cuocolo’s G.C. pinkie ring.

Abbatemaggio stood and spoke for so long that he had to cut a hole in his shoe to relieve the pressure on a severe blister. During breaks he passed his fan mail on to friendly hacks and explained that, if he had ever had the chance to study, he too would have become a journalist.

Il Mattino

’s correspondent had no doubts about Abbatemaggio’s sincerity. Here was ‘a man endowed with marvellous physical and mental solidity, and with balanced and robust willpower’ the Neapolitan daily opined. It was inconceivable that he could have dreamed everything up as the defence claimed.

Even the most audacious imagination would not have been able to create all the interconnecting lines of this judicial drama. Every detail he gives is a page taken directly from life—albeit from a life of crime: it is intense, keen, overwhelming.

The defence also thought that Abbatemaggio’s testimony was dramatic, although in a very different sense. In cross-examination, one lawyer announced that he would prove that this supposed inside witness had gleaned all he knew about the Honoured Society from downmarket plays. ‘Has Abbatemaggio ever been to the San Ferdinando Theatre to see a performance of

The Foundation of the Camorra

?’ Abbatemaggio replied calmly that he only liked comic opera—

The Merry Widow

and the like. ‘Besides, why would I need to watch the camorra performed in the theatre, when I was part of it?’

The quip was greeted with approving laughs from the public gallery.

The defence also tried to discredit Abbatemaggio by questioning his sanity: he was a ‘hysterical epileptic’, they claimed, in the dubious psychological jargon of the day. One expert who closely examined him disagreed, but said nonetheless that he was a particularly fascinating case. Again and again Abbatemaggio responded to those who doubted his evidence with names, dates, and a torrent of other particulars. Perhaps he could be classified as a ‘genialoid’, a rare blend of the genius and the lunatic; his ‘mnemonic and intuitive capacities are indeed phenomenal’.

Abbatemaggio’s credibility as a witness also depended on his ability to tell a story about himself, a story of redemption. He claimed to have found personal moral renewal by exposing the camorra’s secrets to the law. He had

been saved, he said, by his love for the young girl he had recently married. ‘Camorrist told all to win his bride’, was the

New York Times

headline.

Meanwhile, in the defendants’ cage, camorra boss Big ’Enry scowled and scoffed. Wiry, sunken eyed and heavy jawed, he had a disconcerting horizontal scar that ran from the corner of his mouth out towards his right ear. He wore mourning black because his younger brother Ciro, one of the five men who ate at Mimì a Mare on the night of the murders, had died of a heart attack in custody. During Abbatemaggio’s testimony Big ’Enry was heard to mutter the occasional comment. ‘This louse is like a gramophone, and if you turn his handle he goes on and on.’ The label stuck: for the rest of the trial, the defendants would refer to Abbatemaggio as ‘the gramophone’.

When Big ’Enry’s own turn to give evidence came he made an impression that initially surprised many by how eloquent and convincing it was. He explained that he ran a shop in piazza San Ferdinando selling horse fodder—bran and carobs. He was also a horse dealer who traded with military supply bases in Naples and surrounding towns; he had made a lot of money exporting mules to the British army in the Transvaal during the Boer war. He denied being a

camorrista

but admitted that he was rather hot-headed and did sometimes lend money at very high interest rates. It was all a question of character.

Gentlemen of the jury, you need to bear in mind that we are Neapolitans. We are sons of Vesuvius. There is a strange violent tendency in our blood that comes from the climate.

The

Carabinieri

, Big ’Enry concluded, were victimising him and had bribed witnesses. He had suffered so much in prison that he was losing his hair.

Several policemen of various ranks were subsequently called to testify, and reeled off Big ’Enry’s catalogue of convictions. He had begun his career as a small-time pimp. Like many other

camorristi

, Big ’Enry dealt in horse fodder because it provided a good front for extorting money from hackney carriage drivers and rigging the market in horses and mules. They explained that he provided the protection for the high society gambling den run by Johnny the Teacher, and confirmed that he was the effective boss of the camorra. They noted that the nominal boss was one Luigi Fucci, known as ‘

o gassusaro

—‘the fizzy drink man’—for the prosaic reason that he ran a stall selling fizzy drinks. Big ’Enry used him as a patsy, while keeping the real power in his own hands.

Big ’Enry began to look like what he really was: a villain barely concealed behind a gentlemanly façade. Not many of the other defendants came across much better. Arthur Train, a former assistant District Attorney in New York, was one of many American observers at the trial. He noted that

the Camorrists are much the best dressed persons in the court room. Closer scrutiny reveals the merciless lines in most of the faces, and the catlike shiftiness of the eyes. One fixed impression remains—that of the aplomb, intelligence, and cleverness of these men, and the danger to a society in which they and their associates follow crime as a profession.

The Cowherd, the ‘ultra-modern

camorrista

’ whose sexual conquests among the ladies of the aristocracy had reputedly so enraged the Duke of Aosta, was a particularly elegant figure. He too tried to present himself as an honest businessman who had begun by selling bran and carobs and had risen to become a successful jeweller. Only a freakish chain of bad luck had led him to spend several short spells in jail for extortion, theft and taking part in a gunfight, he said. The Cowherd’s refined appearance was compromised by the two long scars on his cheek. ‘Fencing wounds’, he protested. He did at least make a telling point about the notorious ring engraved with Gennaro Cuocolo’s initials: he demonstrated that it was not big enough to fit on his own little finger—and he was a much smaller man than Cuocolo.

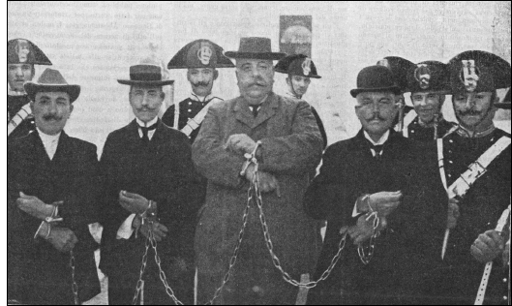

The accused arrive in Viterbo for the most sensational camorra trial in history, 1911. Following the brutal slaying of a former

camorrista

and his wife, the Cuocolo case generated worldwide interest. The man in the bowler hat is Luigi Fucci, ‘the fizzy drink man’, and nominally the supreme boss of the Honoured Society.

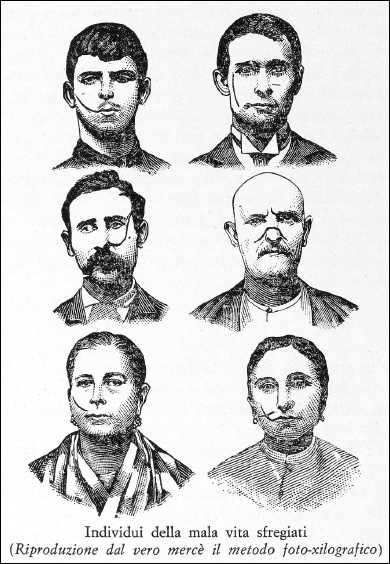

The

sfregio

, or disfiguring scar, was one of many visible signs of camorra power in Naples.

Camorristi

handed out

sfregi

as punishments both to one another and to the prostitutes they pimped. Sicilian

mafiosi

, by contrast, refrained from both pimping and the

sfregio

.

Few of the accused had plausible alibis. Some denied knowing Abbatemaggio, only to be flatly contradicted by other credible witnesses. One

camorrista

thought it was a good idea to have his defence printed in pamphlet form. In it he admitted that the camorra existed but claimed that it was a brotherhood of well-meaning individuals who liked to defend the weak against bullies. This brotherhood’s ruling ethos was what he termed

cavalleria rusticana

—‘rustic chivalry’. Evidently this particular defendant was trying to apply the lessons from the Sicilian mafia’s successful ploy in earlier trials. He cited camorra history too, concluding his pamphlet on a patriotic note by recalling how, half a century ago, when Italy was unified,

camorristi

had fought Bourbon tyranny and contributed to ‘the political redemption of Southern Italy’.

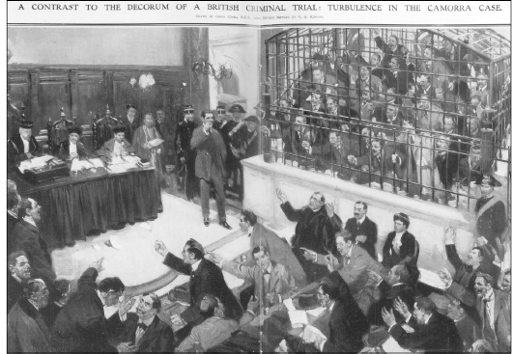

Disorder in court. The chaotic scenes at the Cuocolo trial baffle and repulse observers across the world. From the

Illustrated London News

.

The judge in Viterbo attracted much criticism for allowing the defendants themselves to cross-examine witnesses. These exchanges prolonged proceedings enormously, and sometimes descended into verbal brawls. One

camorrista

, a fearsome one-eyed brute who stood accused of smashing Gennaro Cuocolo’s skull with a club, shrieked colourful insults across the court at Abbatemaggio.

You’re a piece of treachery! And you’ve sold yourself just so you can eat good

maccheroni

in prison. But you’ll choke on those nice tasty bits of mozzarella. You’ll see, you lying hoaxer!

Shut up you louse! Shut up you pederast! I’d spit in your face if I wasn’t afraid of dirtying my spit.