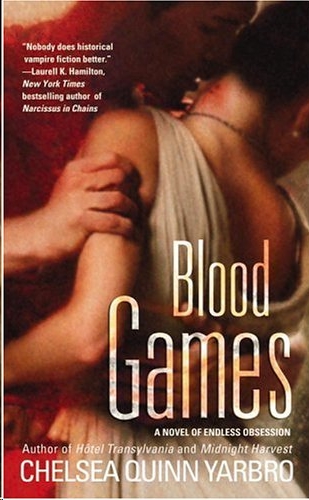

Blood Games

Authors: Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Tags: #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Dark Fantasy, #Occult & Supernatural, #Historical

E-Reads

www.e-reads.com

Copyright ©1979 by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

First published in 1979

Blood Games

Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Copyright (C) 1979 by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Published by E-Reads. All rights reserved.

www.ereads.com

Michael Moorcock

with love and music

This is a work of fiction. Its setting is historical and some of the characters are based upon actual persons living in the time of this novel. All reasonable effort has been made to recreate the conditions and attitudes of first-century Imperial Rome with as few distortions as possible.

The historical events described in the course of the book are reconstructed from various sources, whenever possible from contemporary accounts and eyewitness reports. When such documentation is not available, or reports conflict, the description resulting has been arrived at through exigencies of plot rather than to grind any philosophical or academic ax.

At first, such technological devices as metered chariots and sedan chairs, central radiant heat, indoor plumbing, eyeglasses, assembly-line factories and fast-food stores may seem highly anachronistic, yet such things did indeed exist at the time depicted.

The interpretation of the characters of actual persons, along with those of the fictional ones, is wholly that of the writer, and should not be construed as representing or intended to represent any person or persons living or dead.

TEXT OF A LETTER FROM AN EGYPTIAN APOTHECARY AND SPICE MERCHANT TO RAGOCZY SAINT-GERMANIN FRANCISCUS IN ROME

To the man now calling himself Ragoczy Saint-Germain Franciscus, the servant of Imhotep sends his greetings.

I have your requests for spices and medicines and will do my utmost to fulfill your commands to me. There may be some trouble getting a few of the rarer items, as it is not easy to move about the land now that the Romans are here. Be patient with me, my master, and I will see that you have all that you require of me. Two of the items you specify must come along the Silk Road and it may take more than a year to bring them. You have said that you will wait any reasonable length of time, yet I feel I must warn you of these circumstances. I feel sure you would want me to be confidential in regards to your order, and so I will not mention by name the things you have asked me to get for you.

Earth from Dacia is another matter. We may provide that amply, although I am surprised to find you are without it. Nine large barrels of it come with this letter to you. You say that you are building a villa outside of the walls of Rome and some distance from the Praetorian camp, and I have assumed you need the earth for that. We are also, as partial filling of your order, sending the fine tiles you specified, and dyed cotton and linen in the colors you have stated. By the end of harvest time we should have the cinnabar, turquoise, carnelian, jasper, agate, sardonyx and alabaster in the quantities you wish, and will send them to you as quickly as possible. The selenite might take longer, for moonstones of the quality you wish are not easily found. I will send agents into Parthia and Hind to search. Do not, I beg you, be disappointed if they do not find your gems at once. You say that you can obtain rubies and diamonds, and so I will not search for those. Should you change your mind, you need only send me a message and I will procure the jewels you desire.

You indicate in your letter that you do not anticipate visiting this land for some years. It saddened me to learn of this, for your return is much hoped for among those few of our brothers that are left. You would be welcomed heartily by all that remain here. Our school, of course, now must meet clandestinely, and there is little we can do to change this. Not only do the Romans distrust us, but our own people, seduced by Greeks and Romans alike, think that our ways are outmoded. The priests of Imhotep are become merchants because they fear to heal! Should you come back to us, it might be otherwise.

Forgive this outburst, my master. It comes from my despair, not from your absence. It is well that you are in Rome and not here. Alexandria is a shame to us, and Luxor is forgotten. You told me once that if I should walk into the desert, I would not find a peaceful death, but ravening madness. So I will not walk into the desert, though I think that I have lived too far beyond my years.

Whatever you ask of me, and the rest of us, it shall be done. Yet do not condemn me if I am disheartened.

Farewell, to you and my brother Aumtehoutep?

DUSK HAD FALLEN, turning the very air of Rome an intense blue in the last struggle of day with night. The evening was warm and the breath of the city pungent, but the air in the Greek-style atrium smelled of cinnamon, scented by the dozen little braziers where incense burned. Now the slaves were busy lighting the hanging lanterns and setting out the low tables beside the couches where the guests would recline for the banquet.

Petronius strolled through the atrium, half-smiling as he watched the slaves work. He was tall for a Roman, with fashionably cut brown hair that was touched with gray now. At thirty-four his attractive face had a curiously unfinished look and his dark blue eyes were tired and old under straight brows. Rather than a toga, he wore a charioteer's tunica, but instead of rough linen, his was made of fine white silk. He stopped beside the fountain and sniffed at the water as he caught it in one hand. A faint scent of jasmine perfumed the fountain. Satisfied with the fragrance, Petronius stepped back. Near him, hanging on the bough of a blooming peach tree, a tintinnabulum sounded its little phallic chimes as the evening breeze touched it. Petronius reached out and negligently tweaked the branch so that the tiny silver bells jangled together. He was about to go to the kitchens at the back of the house when his houseman, an old Greek slave called Artemidorus, stopped him.

"Master, a visitor,” said Artemidorus as he hurried into the atrium.

"A visitor? Not a guest?” The banquet would not begin for almost an hour, and it was more usual for the guests to arrive late than early. “Who is it?"

The houseman bowed slightly. “A Senator."

Petronius sighed. “What does he want?” For he undoubtedly wanted something, which was part of the price exacted of those who stood high in the young Emperor's esteem.

"He did not say, master. Shall I refuse him?” The old Greek was eager to do so, and he smiled as he asked.

"No, better not. He'll only come back later and be more insistent. Show him...where?...into the receiving room, I guess, and tell him I'll be with him shortly. It would be a pleasure to keep him waiting, but with guests coming...” He felt resigned to the company of the Senator. “Artemidorus, do you know which Senator this is?"

The houseman paused. “Yes. I know him.” He said it with distaste, and the faintest sign of fear.

"Aaaaah.” Petronius drew the word out. “Tell me."

"It is Cornelius Justus Silius.” There was more disgust in his voice.

"What can that old ferret want with me?” he wondered aloud. “Bring him here, then. And make no attempt to hide our activities. He will want me to include him, and it will be a great pleasure to decline.” He motioned Artemidorus away and signaled one of the slaves to bring a chair from the house.

"Just the one?” the slave asked, leaving off rubbing the tables with lemon rind.

"For the Senator,” Petronius said sweetly, then chose the nearest couch and sank down upon it.

He did not have long to wait for his inopportune visitor. Very shortly Artemidorus returned, escorting the Senator Cornelius Justus Silius. “Good evening, Justus,” Petronius said, indicating the chair the slave had brought.

Justus eyed the chair, fuming at this minor, casual insult.

The Senator was an expert in such matters, having over the years learned how to dash hopes with the lift of his brows. He was close to fifty now, and had weathered three severe political storms since he had come to the Senate twenty-three years before. With a slight shrug of his heavy shoulders he took the chair, concealing his dislike of Petronius with a condescending smile. “I heard you were expecting guests, and so I won't stay."

Petronius leaned back on the couch and watched Justus through narrowed eyes.

"I have a minor problem, and ordinarily I wouldn't trouble you with it, but I haven't been much in the imperial presence of late, and you're more familiar with the latest..."

"Gossip? Quirks? Outrages?” Petronius suggested.

"Imperial tastes!” Justus snapped. “I'm planning on sponsoring a few days of Great Games, and as editor, I would want to present those encounters that would most please the Emperor, particularly if you can suggest some novelty that would satisfy Nero. I'd be much appreciative, Petronius. And while I'm not a rich man—"

"What would you call rich?” Petronius interrupted with a disarming smile. “You have eight estates and your family has always been wealthy, hasn't it? I had not heard that you had suffered any misfortune of late."

Justus moved uncomfortably and adjusted his toga. “It's true that I have some substance, but my lamentable cousin did much to compromise our name when he made that ill-considered alliance with Messalina...Claudius ruined that woman, and Gaius should have realized it.” He watched Petronius closely.

"That was years ago,” his reluctant host said, sounding bored. “Nero is not overly attentive to the glorification of Divus Claudius. Surely a man of your rank and substance does not need a kind word from me."

"Not a kind word, no,” Justus said heavily. “But the Great Games must be spectacular and original enough to bring me recognition once more."

"Why? Are you plotting again?” He asked it lightly, with elegant mockery, but the question was serious.

"I?” Justus shook his head, an expression of gentle sagacity on his rough-hewn features. “No. I should think the family has learned its lesson by now. We know what plots lead to."

"But you seek to return to Nero's notice,” Petronius pointed out politely.

"That's a different matter.” Justus gave Petronius a measuring look. He had heard that Titus Petronius Niger was more subtle than he seemed and more intelligent than was thought. There were those verses, of course, and strange, sarcastic tales he was said to have written. He decided on another tack. “It does me no good at all to sit back, tend my estates and go to the Senate upon occasion if I don't have a sensible relationship with Nero. Think a moment. He could seize my lands, imprison me or my wife, or both of us, he could decide that he must have all my revenues, leaving me not precisely a beggar, but close enough. If he is well-inclined on my behalf, then I need have no worries. It would be a great weight off my mind. I confess, since I've married again, I've felt a growing need to make my position secure, not for myself, of course, but for Olivia, who is certainly destined to outlive me."

"Your first two wives didn't,” Petronius observed.

"Corinna is still alive. It may appear cruel to divorce a mad-woman, but there, what could I do? I had no heirs and was not likely to get them with her. She is well-tended and I have reports from those set to care for her.” He did not want to talk about his first two wives, but it would be unwise to avoid the subject. He knew Roman opinion came out of gossip and rumors, and he could not afford any more hints that Corinna's insanity and Valentina's death were his fault. “Valentina, well, nothing but good of the dead, naturally. An unfortunate young woman."