Blood Games (69 page)

Months after he arrived in prison, Neal still had trouble understanding the chain of events that brought him there, still had trouble accepting the reality of what had happened.

“Murder isn’t part of anything I understand,” he said. “Even after being involved in it, it doesn’t seem like something that really happens. It happened. I can’t change that it happened. If I keep trying to deny that it happened, I’ll just go crazy. But I don’t feel like a murderer. I don’t feel like I helped kill a man. I feel awful that a man was killed and I could have stopped it. Maybe I should feel more remorse for helping kill a man, but I just don’t see that I should feel badly for helping kill a man when I didn’t think a man would be killed.”

Did the harsh reality of prison make him regret talking to the police?

He smiled.

“I have to admit, some days I think I’m a total nut for doing what I did. But no, I can sleep now. I can face my mother and smile and know I’m not holding any terrible secret back. My friends, my family know all about me and they still love me. That makes it all worthwhile, no matter what happens.”

After Neal arrived at prison, Kenyatta wrote to him, apologizing for the way she had treated him in the months after he got out of jail following his confession, enclosing a photo of herself. The letter got sent to several places before reaching Neal, and he was late responding.

“Ah lass,” he wrote, “hearing from you ’tis good for my soul.”

He would be delighted to keep in touch, he said, and would like her to visit sometime, perhaps in the summer.

But he did not add her to his visitor list and did not answer later letters. Finally, Kenyatta went to Neal’s mother to ask her help in arranging a visit, and the two adversaries for Neal’s attentions went together to visit him at Christmas.

Joanne got angry at the cards that came from friends and family after Bart’s conviction.

“Why don’t they just go get a sympathy card?” she said when the “thinking of you” cards began to arrive.

Of course, Hallmark didn’t make cards of condolence for mothers of sons who had been sent to Death Row, and Joanne knew that people were well-intentioned and simply didn’t know how else to respond to such a situation.

For Joanne, what had happened to Bart was worse than death. Death at least was final. A death sentence was torment, death and sorrow dragged out interminably, unbearably.

“We all feel helpless now,” she said. “We feel guilty sitting here watching TV, or drinking a beer, or walking on the beach and knowing that Bart can’t do that. To know that Bart may never put his feet under my table again…”

She began to cry, unable to finish the sentence.

“Christmas and Thanksgiving his chair is there empty. I think of the Christmas decorations I made for all the kids. They always loved putting their own ornaments on the tree. Bart’s not ever going to get to do that again, to be part of that. He’s not ever going to get to take them and put them on his own tree with his own children.”

While Joanne had questions about her failures with Bart (“I can’t help but think there’s something I didn’t do, something I should have done differently, or could have done. I guess every parent would feel that way, but they can’t understand how I feel”), Jim was agonizing about his own guilt in the months after Bart was sent to death row.

He kept going back over the years, trying to figure out what had gone wrong and when, asking himself what he had done or not done, said or not said that might have made a difference in his son’s life.

“At some time, there was a turning point,” he said. “Was there an opening where I could have reached through and got him? Where did I lose him? I feel like there was some point that I lost him.

“Why he’s done the things he’s done, I don’t know if I’ll ever get a good answer. But I feel responsible that I didn’t reach him, that I didn’t try harder to get to him.

“I think I just closed my eyes to things I should have been concerned about. I can see now that there were warning signs. Now, with twenty-twenty hindsight, I feel like there were needs I didn’t meet. Whether I could have reached him or not, I don’t know. Bart retreats back into himself and it’s hard to get through to him. But I have these nagging questions that I can’t shake loose. I didn’t have a father either. This father-son relationship, I didn’t have any experience to go back to.”

Wayland Sermons had been so upset by Bart’s death sentence that he told Judge Watts he didn’t want to handle Bart’s case on appeal. The judge did not want the overworked appellate defender’s office to have to deal with so complex a case and asked several prominent lawyers in the state to consider taking it. All declined. When Judge Watts called Sermons to ask him to reconsider, Sermons reluctantly accepted.

Only a few weeks later, Sermons was heartened by a five-four decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of a North Carolina man charged with killing a sheriff’s deputy. The court ruled that state law made it too difficult for jurors to consider mitigating factors in capital cases and granted the man a new sentencing hearing. The ruling meant that almost all Death Row inmates would get new sentencing hearings when that time came in their appeals processes and Sermons was certain that included Bart. Later in the year, a new murder trial and Sermons’s inexperience as an appeals lawyer caused him to withdraw from conducting Bart’s appeals, but he still intended to represent Bart at the new sentencing hearing when it was ordered.

On April 6, 1990, the date originally set for Bart’s execution, Sermons visited him to talk about the case. Bart arrived at the visitor cubicle wearing small, round John-Lennon-style sunglasses, ironically, the same type of glasses that Lieth Von Stem wore in his long-haired, pot-smoking college days, although Bart couldn’t have known that. He had bought the glasses from another inmate.

“Helps me not see so much,” he said. “The less I see of this place, the better.”

In the spring of 1991, a teacher at Bartlett-Yancey High School sent a videotape to John Taylor. During his investigation, Taylor had shown the teacher the green army knapsack found on the back porch of the Von Stein house, hoping that she could identify it as Bart’s, but the teacher couldn’t remember the kind of book bag Bart had carried in high school. However, while watching a videotape that she had made in one of her classes while Bart was a senior, she realized that Bart was in it—and she saw something she thought that Taylor might find interesting. On Bart’s desktop was his book bag: a green army knapsack.

In his first months on Death Row, Bart often tried to think back to what he was doing on the same day a year earlier when he was free on the streets outside the prison walls. His first anniversary on the block caught him by surprise. He saw the big stock car race at Daytona on TV and remembered that he’d watched it in this same place the year before.

Much had changed in that time. He had become resigned to his existence, miserable though it was. Weathering the storm. He read a lot. He was keeping a journal. He had begun writing a novel. He still fiercely maintained his innocence, and he did not like to speculate about what might happen to him, but his prospects for a new sentencing hearing gave him hope.

“I like to think that maybe I’ll get off Death Row and spend fifteen or twenty years in prison and get out,” he said. “All it is is hope. You can only hope for the best and expect the worst.”

All of his friends from his earlier days in Raleigh had drifted away. He didn’t hear from any of them anymore. Hank had returned to Wisconsin to be with his mother, who was dying of cancer.

Bart had one new friend, a rock station DJ who’d become intrigued by him and visited regularly. But his most frequent visitor was his father.

Jim had sold the farm where he had been so happy in Caswell County and bought an antebellum house down the street from his mother in Milton that he and his girlfriend, Kathy, were restoring. He’d been transferred back to Raleigh in his job and worked only a short distance from the prison.

He enjoyed his visits with his son and Bart looked forward to them, too. They never discussed the case or Bart’s situation.

“I’m not a preacher or a counselor,” Jim said. “I’m just his dad. We talk about things. I think I understand Bart better than I did before. I feel closer to him, I don’t know why. In some ways, I feel like I’m one of his only friends. He needs me and I’m there.”

Gallery

LEFT: Bart Upchurch when he was arrested on a drug charge in the spring of 1989. RIGHT: Bart at the age of five. (JIM UPCHURCH)

LEFT: While in high school, Bart posed as a desperado in a gag photo made at the state fair. After going away to college, he became the real thing. (JIM UPCHURCH) RIGHT: Bart at the time of his arrest in high school.

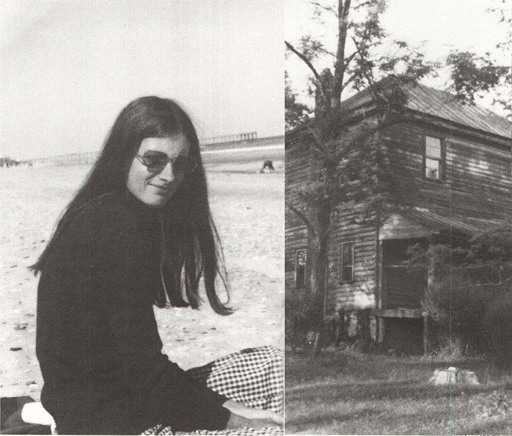

LEFT: Joanne Upchurch gave up a full scholarship and dropped out of college to marry Jim Upchurch and move to a farm. (JIM UPCHURCH) RIGHT: The farmhouse where Jim and Joanne moved with their young children. Although the family lived a near-primitive existence in this house, Jim found his greatest happiness here. (JIM UPCHURCH)

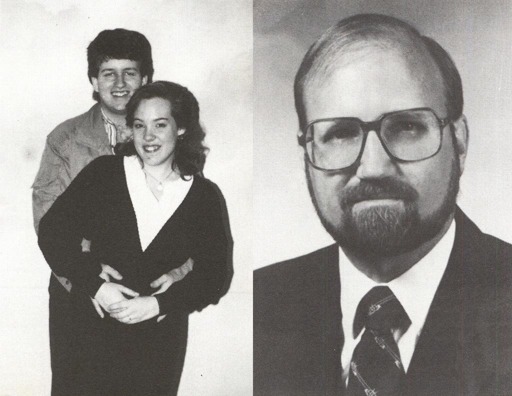

LEFT: Jim Upchurch, whose family was considered to be the “combread aristocracy” of Caswell County, North Carolina. (JIM UPCHURCH) RIGHT: Neal Henderson’s IQ qualified him as a genius, but he flunked out of North Carolina State University in the spring of 1988. (KENYATTA UPCHURCH)

LEFT: Neal with Kenyatta Upchurch, Bart’s cousin. (KENYATTA UPCHURCH) RIGHT: Lieth Von Stein, the executive who was murdered in his bed in July 1988.

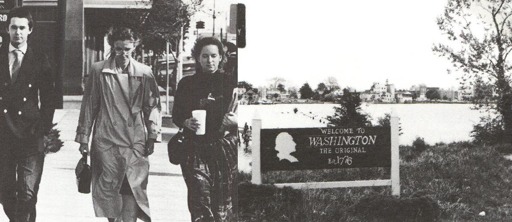

LEFT: Bonnie Von Stein could not believe that her son, Chris Pritchard, had anything to do with the murder of her husband and the attempted murder of herself. This photo was taken on the day Chris testified at Bart’s trial in January 1990. Bonnie, her daughter Angela, who slept through the murder, and Chris were returning to court after lunch. (MICHAEL BARKLEY) RIGHT: Washington is called Little Washington in the rest of North Carolina. But residents of the river town prefer to call it the original Washington, because it was the first town to be named for the country’s first president. (JERRY BLEDSOE)