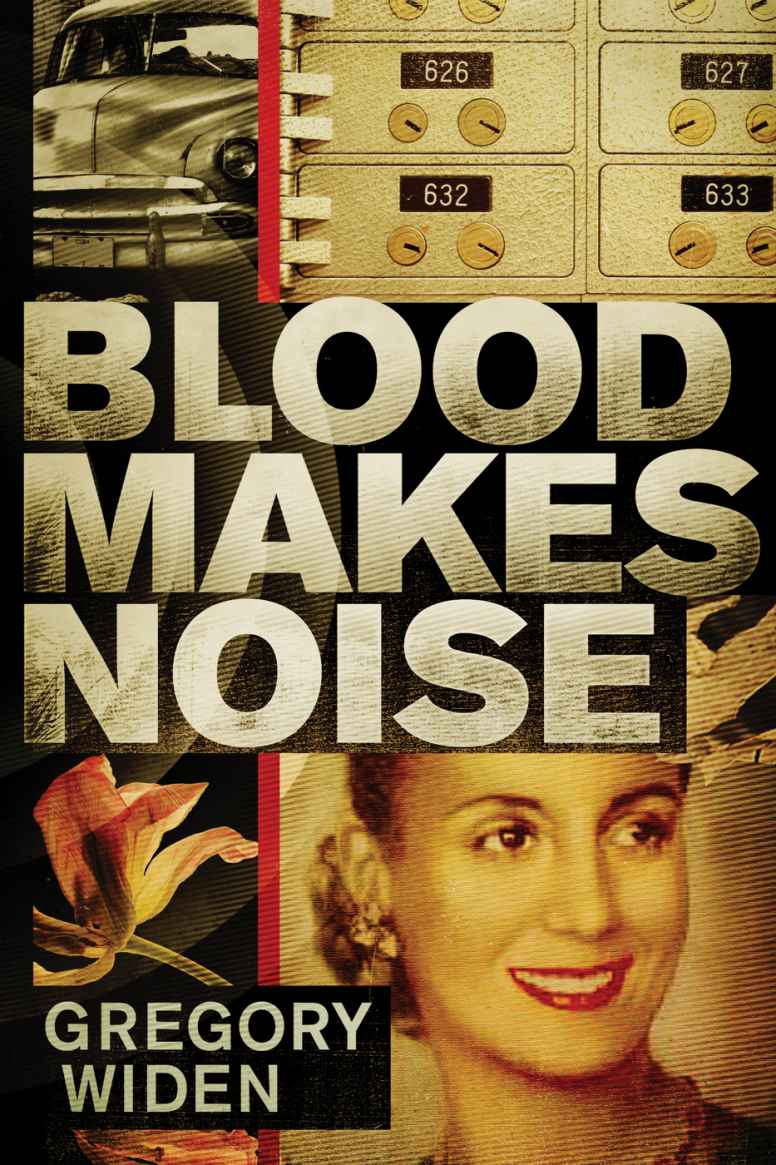

Blood Makes Noise

Authors: Gregory Widen

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright © 2013 Gregory Widen

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Thomas & Mercer

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN-13: 9781611098990

ISBN-10: 1611098998

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012918814

For my parents

Based on True Events

PROLOGUE

April 21, 1947

I

t was late, nearly midnight, and everyone else had left the bank hours ago. Home to wives, girlfriends, warm social dinners made more perfect in his mind because he had neither friends nor dinner invitations—just his last name on the front of the building and a hatred for this minor errand-boy assignment he’d been left with.

His desk was large, prominently placed, and if you didn’t know better, you’d think this was a young man of responsibility. But everyone did know better—even, seemingly, the ancestral portraits glaring at him now.

The bank was an old, family one. Never a fertile dynasty, theirs produced a single son each generation to carry on the family crime. But every gene pool has its shallow end, and this son was trusted with little but the time to concentrate on the growing shame that was becoming his inheritance.

And so Otto Spoerri sat there, waiting, and threw crumpled paper balls at a wastebasket he never hit.

The note, hand delivered that afternoon, was predictable enough. A wealthy foreign individual—unnamed of course, this being a Swiss bank—would send a representative at midnight—it was always midnight, wasn’t it?—to arrange a large, VIP safety deposit box. The representative undoubtedly would be some colorless suit straining under the weight of some monster or other’s fleeing, bloodstained fortune.

At twenty past midnight he was dozing when there was an insistent rap at the rear glass doors. Otto got up and opened them on a broad-shouldered man in livery costume. “Herr Spoerri?”

“Of course.” Who the hell else would be stuck here at this hour? The livery costume nodded, walked back to the idling limousine, and opened the rear door.

From it emerged a beautiful woman in her late twenties. She wore mink, her blonde hair up in a fierce chignon. Otto Spoerri recognized the face immediately, and his surprise was sufficient enough to leave him momentarily without manners.

“Are you the banker?” she asked in Spanish. Finally coming to attention, he took her hand and bent with a snap. “Senora. I am surprised. Please, welcome to Kredit Spoerri.”

She nodded. He led her inside, offered a chair, muddled his university Spanish. “You needn’t have come in person, Senora. We accept transactions through intermediaries.”

“Had I wanted intermediaries, Herr Spoerri, I would have sent them.”

“Of course.”

He laid out the relevant papers for her to complete. Eva Duarte Perón. Evita. First Lady of Argentina—a dictator’s wife but widely considered the real power—she was here on her grand European tour. In the utter dreariness and hunger of postwar Europe, the more dreary and starving the country, the more fabulous—if often clenched—the reception this cattle-rich nation’s First Lady had been given.

But things had gone sour in Switzerland. The world’s recent insanity hadn’t lapped over this side of the mountains, and its people were neither hungry for Argentine beef nor amused by its demanding maiden. Otto could glimpse tomato stains clinging to the limousine’s finish, souvenirs from the Zurich crowds protesting her visit.

“I apologize for the hour and whatever appointments I’ve kept you from. Are you married, Herr Spoerri?”

“No, Senora.”

“You do not love women?”

“Perhaps too much, Senora.”

“If you cannot love one woman, then you can love nothing.”

“Wise advice, Senora.”

“The marriage between my husband and I is the light of my nation.”

Her bosom swelled under cashmere, and he wondered if it was

my husband

or

my nation

that did it.

She sat back, crossed her legs, and took a cigarette from her purse. Otto struck his lighter and held it across the desk. She placed the cigarette in her mouth, bent forward, and, as the flame licked the end, turned the shaft between red lips and allowed her eyes to rest an instant on his.

“Our standard procedure, Senora, is to issue you a completely private account number. With this—”

“I would like a key.”

“Senora?”

“One key. Nothing more.”

“It is usual to have an authorization list of who may have access to the box. It provides security against—”

“No list. Just a single key. The key, only the key, is my authorization. It will, however, be a very

special

key.”

“All our keys at Kredit Spoerri are special, Senora.”

“I am quite sure. But this key is already made. It is manufactured to such a temperance that if a false one is placed in the lock it will disintegrate instantly.”

“I’m not sure I am aware of such a lock.”

“It too has already been made and will be installed in the box.”

“An outside lock? No security list? I’m afraid such an arrangement is unprecedented.”

She took a breath from her cigarette and rested her elbow on the chair’s armrest, cocking the smoldering end off the side of her cheek. “Of course.”

What a woman, with her harlot lips and shopgirl swagger, the heat of an absolute confidence that dried his eyes. A woman who’d come to a country that despised her, waded through seething crowds and splashing fruit, all to sit in the city’s oldest bank at midnight and calmly wait for what she wanted, turning the cigarette between moist lips, and the contest was over before she ever walked in—over the day she was born.

“Such an arrangement is probably against Swiss banking law.”

“I’m sure.”

“I’d be putting myself personally at risk.”

He watched as his words were dismembered and eaten by smoke.

“Yes.”

And he thought of her in bed. Imagined that focus pounding itself down on him. As if divining his thoughts, she leaned forward. “I will deal only with you, Herr Spoerri. There will be no statements sent to me—if I need information I will contact you alone. My name will be on no records. There will be only our friendship, our understanding, and the key, for which I will pay handsomely, also to you.”

“Why should I do this?”

“Because you are a young man in an old man’s bank. A young man with dreams of a different future. I would like to be a part of that future.”

Smiling from a place unmapped, she handed back the sheaf of government deposit forms—blank.

“If I may view my deposit box now, Herr Spoerri.”

And he lingered, jealous of the moment, listening to the rustling of her stockings, then stood with proper Spoerri formality. “This way, Senora Perón, please.”

Her limo driver brought in the leather cases, nearly a dozen, and in private Evita and he transferred the contents to their new home

and sealed it all with the custom locking mechanism, carried in a shiny aluminum attaché.

Otto knew he would never tell his father, or the bank, that the box was Eva Perón’s. He printed up the single sheet with the number and laid it in her warm palm. She left then, and he had waited for her return. There followed hand-delivered notes, short, fragrant sentences. But Eva Perón herself never appeared again. In five years she was dead and the box remained, untouched, and he grew older, coming to the vault sometimes, sitting there, thinking of it and her.

Her legacy had plenty of company. This was a room full of midnights: tax evaders, gangsters, Nazis—many dead, like her, their reeking fortunes marooned under the devil’s quilt of secrecy that was his family’s crime. His nation’s.

J

uan Duarte never liked the river, and now it lay outside his window, scaly with moonlight, taunting him. It was his first memory of this cursed city and would likely be his last. A bitter wind off its surface rattled his reflection—the same wind that had taken his sister, coming for him. Juan drew in a tired breath and dreamed of floating away. To his village, its hopeless roads. They had danced circles in the dust as children there, his sister and he. They had needed only each other…

“Where is it?”

Juan recognized the voice without turning. Bluff and baritone, with the crack of jackboots. Juan’s eyes stayed on the window. “I don’t know.”

He wished he sounded tougher, for once confident in the presence of the peacock. Instead his voice was only sad.

“Come, Juan, be reasonable”—spoken with a reasonable voice. This would be the peacock’s shadow, announced—always—with the tap of his dog-headed cane; everyone’s favorite demon uncle. “You’re among family. How can you keep secrets from your own blood?”

“I tell you, I don’t know.” A gust of wind jarred his reflection: pencil mustache and hair pressed flat with brilliantine. A dandy.

“Liar! She…” The baritone peacock again, his voice breaking on that word as it broke every time he uttered it since…

“She was your sister. She told you everything.”