Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain (18 page)

Read Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain Online

Authors: David Brandon,Alan Brooke

The railway police, however, were prepared to take the risk, understandably anxious not to allow the murder of one of their number to go unpunished. To their chagrin, however, the case against the men was conditionally discharged on the grounds of insufficient evidence. The case remains unsolved to this day.

Found: Body in a Tunnel

The original Merstham Tunnel was built for the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway in 1839. A new tunnel was built in 1899 alongside and it was in this later tunnel that a gang of track workers made a gruesome discovery around 11p.m. on Sunday 24 September 1905.

The men were doing routine maintenance work on the track by the fitful light of oil lamps which cast weird shadows on the sooty walls of the tunnel. It was dangerous and uncongenial work but it had to be done, and the fact that there were fewer trains about at this time of the evening did at least reduce the ever-present fear of all platelayers and gangers which was, of course, that of being run down by a fast-moving train, always a possibility even with vigilant lookouts.

In charge of the gang was William Peacock, who was moving somewhat ahead of the rest of the men when he discovered something lying by the side of the track. As he moved nearer he realised to his horror that it was the badly mutilated body of a woman. One leg had been severed cleanly, the face was badly knocked about and bloodied and the left arm brutally crushed. The stationmaster at Merstham was immediately informed as were the police. The body was removed and temporarily housed at the Feathers Hotel where an inquest would take place. There was nothing on or around the corpse which gave any clue to its identity.

The original theory was that the woman had committed suicide but foul play could not be ruled out. Large numbers of people were interviewed by the police, some of them giving answers which were unsatisfactory and needed to be checked out. This took several days and the police acknowledged that they were no nearer identifying the woman. Then, out of the blue, a man came forward asking to be allowed to view the body. This was an unusual request, and given that there were many odd people about the police took a lot of persuading before acceding.

Obviously it was not a pretty sight but the man told them that it was the remains of his sister Mary Sophia Money. She had been just twenty-two years old, was unmarried and had worked in a dairy in a clerical capacity. She lived at Lavender Hill in south-east London. She was small, although well-built and altogether an attractive young woman. Men would have wished to get to know her but she certainly did not seem to have a regular ‘admirer’. Her brother could not furnish any reason why she might have committed suicide.

What began to militate against the suicide theory was that she had clearly been gagged. It was hard to believe that someone contemplating suicide would gag themselves so as not to make any noise. Examination of where the body was found suggested that she had been thrown from the train and

had hit the tunnel wall where there were marks as if she had slid down the tunnel-side, her fingers gouging out the soot. As she slid down the wall it was likely that one of her legs fell over the rail and was severed when the wheels went over it.

Enquiries revealed that on the day in question Mary had told a friend that she was going out for a short while but she never returned. At about 7p.m. she had gone into her local sweet shop as she did regularly on Wednesdays and Sundays. She had chatted briefly and told the shopkeeper that she was going to Victoria. Evidently Mary had told two different stories about what she meant to do and the police concluded that the deception was intentional and that she was going to a clandestine meeting with a person unknown at a destination equally unknown.

She certainly did go to Victoria because a ticket collector recognised her from a photograph. What seemed odd was that she was not dressed for walking or for going any great distance. What then had she been doing on a train destined for Brighton? Did she meet up with a paramour unknown to her family? Did she get on the Brighton train with this man and why? What happened between the couple in what was presumably an otherwise empty compartment? Did he make sexual advances which were rejected whereupon he lost his temper and threw her out of the train in a fit of pique? Questions, questions, but no answers.

It did emerge that a signalman on duty watched a train go past that day and saw what he thought was a struggle taking place in one of the compartments but even this was not much help. The murderer of Mary Sophia Money was never found.

Murder on the North Eastern Railway

In the age of relative innocence that was Britain in the years leading up to the First World War, it was a common practice for clerical workers to travel around on public transport carrying bags containing the wages of the employees of the companies they worked for. Sometimes they carried amounts that by today’s values would be tens of thousands of pounds.

On 10 March 1910 John Nisbet, who lived in Heaton Road on the north-east side of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, was at the city’s Central station carrying a leather bag containing

£

370 9

s

6

d

for the workers of the Stobswood Colliery Company. He was on his fortnightly trip from the colliery to Newcastle with a company cheque which he had cashed at Lloyd’s Bank. This involved a return journey on the North Eastern Railway from Stannington station, the closest station to the pit where he worked. Although the line on which the train ran was a main line, this particular train was a humble and lightly used

stopping train calling at all stations to Alnmouth, where it terminated. Such trains often had average speeds of little more than twenty miles per hour.

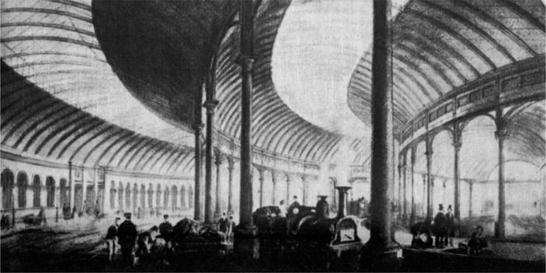

Newcastle central station is by some distance the largest nineteenth-century building in the city. Much of it is the work of John Dobson, who designed many of Newcastle’s finest buildings of that time.

Nisbet, who was well known, was seen by a number of people at Newcastle Central station before he caught the stopping train back to Stannington. They included two other cashiers working for colliery companies who were engaged in the same duties as himself. These witnesses saw Nisbet walking the platform with a man called Dickman with whom he got into a compartment towards the front of the train. Dickman was wearing a light-coloured overcoat.

Nisbet was an uxorious husband and it was the regular practice for his wife to come to Heaton station to meet the train. It usually halted there for a few minutes, during which time he lowered the carriage window and the couple then perhaps proceeded to whisper sweet nothings to each other. On this occasion the train halted only briefly and she just had time to note that another passenger was sharing her husband’s compartment. He was wearing a light-coloured overcoat but his collar was raised and it was impossible for her to tell whether she knew him.

At Stannington the two other cashiers alighted from the train, one of them giving a nod to Nisbet as he passed the compartment in which he was travelling. He noted a man sharing Nisbet’s compartment. He wore a light-coloured overcoat. If the cashier thought it odd that Nisbet was apparently

making no effort to leave the train himself he said nothing and had soon forgotten the matter.

The train puffed wearily on its way calling a few minutes later at Morpeth. There were few passengers alighting but one who did handed the ticket collector half of a return ticket from Newcastle to Stannington and he proffered the excess fare. It was our man in the light-coloured overcoat. Eventually the train steamed into Alnmouth where the practice was for a porter to examine all the compartments before the train was prepared for its return trip. He opened a compartment in the leading coach and then staggered back, vomiting violently.

The body of a man was lying spread-eagled and face downwards on the floor in a pool of blood. Clearly a murder had taken place but it was also immediately evident that a violent struggle had also occurred. An initial examination by the local police, quite excited because they could not remember the last time they had had to deal with a murder, showed that the man had been shot five times in the head. Two bullets were still lodged in the victim’s skull. Various items belonging to Nisbet – it was of course he who lay prostrate on the carriage floor – were quickly identified. The post-mortem showed that the two bullets in his head had been fired from different guns.

With admirable promptness the Stobswood Colliery Company offered a reward of

£

100 for anyone providing information that would lead to the arrest of Nisbet’s killer. Very quickly, Dickman became the focus of attention. The police started with an informal chat. Dickman was only too anxious to help in any way he could, or so he said. Yes, he said, he had indeed been at Newcastle Central station with Nisbet but had parted from him before the train left and had travelled in the same train but in a different compartment. Again he was apparently happy to co-operate with the police when they suggested that he should accompany them to the station and provide a signed statement. So far it was all a bit too glib.

The wheels soon started coming off the information that Dickman volunteered. Why, if he had booked to Stannington, had he somehow contrived to miss that stop and been carried on to Morpeth, the next station down the line? The incredulity of the police gathered momentum as he explained that, after paying the excess fare and leaving Morpeth station with the intention of walking back to Stannington, he had felt poorly and had rested by the side of the road. The purpose of his journey, Dickman said, was to see a man at the Dovecot Colliery. While he had been resting by the wayside, Dickman said that he had met and chatted with a man called Elliot who would vouch for him. The police took careful note of all this but decided to search his house.

Various items were removed for examination. They included some gloves which were bloodstained and some paraffin stains which might have

suggested that attempts had been made to remove the traces of blood. No firearms were found. Dickman had something of what might be described as an ‘alternative’ lifestyle, spending a lot of money gambling – and usually losing. However, this was not illegal and there was nothing to suggest that the money he spent feeding his habit had been acquired dishonestly. His financial affairs were chaotic, largely it seems because he was grossly incompetent and he used a number of aliases, but again that was not actually illegal either. He admitted that a parcel containing a gun had been delivered to offices he rented in Newcastle but he claimed that it was a mistake by the company, to which he had immediately returned the gun.

Alnmouth is lucky still to be on the railway network after decades which were so unkind to small wayside stations situated on main lines. Here an express of the erstwhile Great North Eastern Railway enters Alnmouth station.

All the police had were various items of largely circumstantial evidence, a suspect who they felt certain was their man and a deepening sense of frustration. The issue was how to get a case that would stand up in court. Oddly Mrs Nisbet had not at first mentioned seeing Dickman, who she knew, in the same compartment as her husband when the train had called briefly at Heaton, and she only made this revelation under closer questioning later. This was only one of a number of questions that served to confuse. However, as the days gave way to weeks it was clear that the case was going cold.

On 9 June the leather bag in which Nesbit had carried the wages was found at the bottom of a mineshaft, not far from Morpeth station and adjacent to the road along which Dickman would have walked to Stannington station. Unfortunately this bag failed to furnish any useful clues. The case went to court and Dickman was found guilty of murder. This verdict caused a storm of protest and the Home Secretary felt obliged to allow the case to be referred to the Court of Appeal.

In spite of the anomalies this court confirmed the initial verdict and the result was that Dickman was hanged at Newcastle Prison in August 1910. His last words were, ‘I declare to all men I am innocent.’ Forensic science was in its infancy at the time. Had modern techniques been available to them, Dickman’s counsel would almost certainly have persuaded the jury to return a verdict of not guilty.