Blood Work (16 page)

Authors: Holly Tucker

One month after his arrest Oldenburg's dire situation took another turn for the worseâand once again, Jean-Baptiste Denis was at the center of the problem. Since its beginnings in 1665, the

Philosophical Transactions

had been considered nearly synonymous with its editor, Oldenburg. Clearly he was in no position to arrange for the publication of the journal's next issue. Yet, by some mystery, a new issue did appear on newsstands and in hawkers' hands on July 22. The issue featured a full translation of Denis' controversial “Letter Concerning a New Way of Sundry Diseases by Transfusion of Blood”âincluding the opening portions in which the transfusionist credited the French with originating the procedure. There was something suspicious about this issue from the beginning: It carried the correct date and was paginated consistently with the previous issue, yet it lacked the standard

Philosophical Transactions

header.

Historians have speculated that, during Oldenburg's absence,

Royal Society president John Wilkins had arranged for the publication of this next issue of the

Philosophical Transactions.

24

Yet Denis' letter had created an uproar among Royal Society members, so it is not entirely clear why Wilkins would have reprinted it without commentary or disclaimer. Another, perhaps more likely possibility is that the issue was a counterfeit created for financial gain or as an effort to construct additional evidence against Oldenburg and the treason charges he faced. There is no archival proof for either explanation, and the true circumstances behind this anomalous issue will forever remain a mystery. In any case, one thing is certain. Oldenburg was enraged when he discovered that the

Philosophical Transactions

had been published without his approvalâand was doubly anguished to learn that his cherished journal had been used to circulate Denis' lies.

The Anglo-Dutch hostilities ended on July 31 with the signing of the Treaty of Breda. Animosities and suspicions subsided, and soon many of the men who had been charged with treason were exonerated. Two months after his arrest a grateful Oldenburg was released from the Tower. He left immediately for the countryside in order to recover from his hair-raising ordeal. “I was so stifled by the prison air,” Oldenburg wrote to Boyle shortly after his release, “that as soon as I had my enlargement from the Tower I widened it, and took it from London into the country to fan myself for some days in the good air of Crayford in Kent.” Still, he worried deeply about his reputation and knew that he needed desperately to prove his allegiance to his adopted country. “My late misfortune I fear will much prejudice me,” he wrote, “many persons, unacquainted with me, and hearing me to be a strangerâ¦spread it over London, and made others have no good opinion of meâ¦. I hope I shall live fully to satisfy his majesty, and all honest Englishmen of my

integrity and of my real zeal to spend the remainder of my life doing faithful service to the nation, to the very utmost of my abilities.”

25

When Oldenburg returned to London, he still had much unfinished business when it came to Denis and the havoc the French transfusionist had caused in the Royal Society and for Oldenburg personally. Oldenburg also had to smooth many ruffled feathersâstarting with Richard Lower's. Lower wasted no time in arriving unannounced at Oldenburg's home in order to lodge a complaint. The normally stout Oldenburg looked gaunt; he had not eaten well in the Tower and had only recently regained his appetite. Weakened and pale, Oldenburg approached the enraged Lower with deference and begged him to believe that he had had no role in the publication of the spurious issue of the

Philosophical Transactions.

If he had indeed been the one to publish Denis' letter, a nervous Oldenburg explained, he would have most certainly added an “Animadversion” that refuted Denis' outrageous claims. Oldenburg promised Lower that the next issue of the

Philosophical Transactions

would make it abundantly clear that Denis was a liar.

26

On September 23 Oldenburg made good on his promise. He set the record straight in a new issue of the

Philosophical Transactions

, one that covered all that had gone unpublished while he had been imprisoned in the Tower. “It is notorious,” Oldenburg wrote, “that [transfusion] had its birth first of all in England; some ingenious persons of the Royal Society having first started it there several years ago and that dexterous Anatomist Lower reduced it into practice, both by contriving a method for the Operation, and by successfully executing the same.”

27

Oldenburg reminded readers that earlier issues of his

Transactions

had documented this abundantly.

A month later the secretary of the society dedicated another full issue of the

Philosophical Transactions

to exposing yet again the arrogance of the French transfusionist. In particular he charged Denis with a shocking disregard for the safety of his patients. If the English were moving more slowly than the Frenchâor more particularly, DenisâOldenburg emphasized that it was because his fellow countrymen were practicing an abundance of caution. “They [the French] must give us leave to inform them of this Truth, that the Philosophers in England would have practiced long ago upon Man, if they had not been so tender in hazarding the life of Man (which they take so much pain to preserve and relieve.”

28

Oldenburg knew that his refutation of Denis' claims, no matter how spirited, would likely be insufficient for him to regain all that had been lost. It must have come as some consolation, however, that one of the highest-placed members of the French court had also agreed that Denis had been out of line. Even the most prudent of English censors could not have taken exception to the letter that Louis XIV's secretary, Henri Justel, sent Oldenburg later in the fall: “I must admit that [Denis] was too credulous in accepting the statement of those who said that transfusion was discovered in France rather than in England. I have told him he ought to inform himself more carefully than he has done. All honorable men agree with your opinion.”

29

Denis had no intention of heeding Justel's warnings. The French transfusionist was more than aware of the furor that was directed against him from all corners, both at home and abroad. Truth be told, he reveled in it. A man of humble birth, he had beaten the odds and had come much further than anyoneâperhaps even heâwould have thought possible. He was not going to stop now.

BEDLAM

I

t would be a long time before Oldenburg forgot the personal and financial toll that the transfusion controversy had taken on him. Denis may have stretched the truth about transfusion's origins, but neither Oldenburg nor the English scientific community could deny that the French had won the race for the first human blood transfusion. Now the fellows of the Royal Society wondered if they had been too cautious about experimenting with the procedure in humans. It was no secret that Edmund King and Richard Lower had been ready for nearly six months to begin human experiments. But they had been waiting for the “removal of some considerations of a moral nature”âthat is, a stronger consensus in the Royal Society that such trials could, and should, be attempted despite their evident dangers. The “ingenious” Doctor King documented this timeline in a letter he sent to Oldenburg in the weeks following the secretary's release from the Tower; his clear intention was to see it printed in the

Philosophical Transactions.

Oldenburg was happy to oblige. If anything his time in prison had made him an even more dedi

cated advocate of the English scientific cause. He wanted there to be no doubt of his loyalties to his adopted country and to his colleagues at the Royal Society. King's letter was published in full on October 21, 1667:

Sir,

The method of transfusing blood you have seen practiced, with facility enough, from beast to beast; and we have things in a readiness to transfuse blood from the artery of a lamb, kid, or what other animal be thought proper, into the vein of a man. We have been ready for this experiment for six months, and wait for good opportunities, and the removal of some considerations of a Moral Nature. I gave you a view, you may remember, a good while ago, of the Instruments I think very proper for the Experiment, which are only a silver tube, with a silver stopper somewhat blunted at one end, and flattened at the other for the conveniency of handling, used already on beasts with good success.

1

While the English hesitated, Denis had pouncedâand taken all the credit. Trying not to look back at lost opportunities, Oldenburg was now more certain than ever that the English needed to launch boldly into human trials once and for all. One month after his “enlargement” from the Tower, Oldenburg stood in front of his colleagues and made a motion before the entire Royal Society that blood transfusion “be prosecuted and considered, in order to try it with safety upon men.”

2

His proposal helped mend fences with critics who had criticized him for not doing enough to promote the English cause, and it was accepted without hesitation. The English were now back in the game.

Refusing to be scooped again, the entire Royal Society worked concertedly to prepare for human transfusion. In haste Rich

ard Lowerâthe English “father” of blood transfusionâwas appointed an official fellow of the Royal Society. The society rented a room near their regular meeting place where the anatomist could perform his experiments in collaboration with King. Lower's laboratory space was conveniently situated along the Thames and offered a view of the river; but, more important, it provided an easy means to discard the carcasses and entrails of the animals on which they would experiment. At the next meeting of the society, King read aloud his detailed “method of transfusing blood into a man” and requested that it be registered in the official society record. The only thing that remained now was finding a willing patient.

Jean-Baptiste Denis' animal-to-human trials had been performed first on a boy suffering from an untreatable fever; his second patient was a healthy but drunken middle-aged butcher. For the English to distinguish themselves in the experiment, they would have to select a subject who was very different from those in the French trials. Yet, their first patient would also have to be someone who would survive the blood transfusion and, better still, show a marked improvement in health because of it. At one of the society's next meetings, George Ent, a respected anatomist and close friend of the late William Harvey, proposed that the society try the experiment on “some mad person in the hospital of Bethlem.”

Bethlem, or Bethlehem, Hospital was founded in 1247 by the religious order of Saint Mary of Bethlehem. Situated just east of Bishopsgate and outside the walls of London, it served initially as a hospice for the ill and poor of the community. In 1547, however, Henry VIII claimed the hospital on behalf of the government and officially declared it London's home for “melancolicks” and the “troubled in the mind.” Now, a century and a half later, the hospital was overflowing with patients, pestilence, and the never-

ending din of human misery. Since the Middle Ages, Bethlem had also been called Bedlam; and the asylum was the very incarnation of the chaos with which its name would become synonymous. Bedlam was comprised of just a few small stone buildings, a tiny church, and a garden. Conditions were lamentable, if not horrific. The hospital was perennially understaffed. Raw sewage lay stinking both in-and outside the living quarters, which were crammed with filthy, suffering men and women. The Great Fire of London the year before had spared the hospital; and the frenzy of new construction throughout the city simply underscored Bedlam's dilapidated and brutal state of affairs. Shivering under leaking roofs, the inhabitants of Bedlam were tormented twofold: by their troubled minds and their hellish living conditions.

If the “horrors of Bedlam” were undeniable, they were doubly so for the most agitated and menacing of patients, who were often chained to the walls. There is little doubt that early English society was violent, even when compared with modern standards. Hitting and flogging were common in the general populace, especially toward persons of subordinate status, like women and children. But Bedlam's chains and unfettered violence were more a manifestation of the fears of those who came face-to-face with uncontrollable madness than they were about real hopes of curing the asylum's condemned. Extreme madness was unsettling and needed to be beaten back at all costs. Meanwhile, those who suffered only mild mental illness did not evoke such intense reactions and were more easily tolerated. In fact, as a means to ease overcrowding, the less “extravagant” Bedlamitesâor “bedlam-beggars” and “Tom O'Bedlamers,” as they were also calledâwere released and given license to beg. They were recognizable by a tinplate badge that they wore on one of their arms, which allowed officials to return the mentally ill to Bedlam, should their demeanor move from mild lunacy to full-out insanity.

3

In early Europe human experiments were rare but not unheard of. The noted chemist Robert Boyle had tested laundanum, an opium-based tincture, on one of his servants, who suffered regular nosebleeds. In 1650 he had also paid a man to let himself be bitten repeatedly by snakes in order to test the hypothesis that a hot iron applied near the bite would neutralize the poison. The cure worked, and the volunteer earned a living by repeating the experiment for curious onlookers.

4

Bedlam collected men and women along a broad continuum of health and illnessâand as such, promised a wealth of poor souls on which blood transfusion could be tried. In short order a committee comprised of Richard Lower, Richard King, Robert Hooke, and Thomas Coxeâall men with hands-on experience in canine blood experimentsâwas charged with visiting the asylum. Their task: to pick just the right subject for their experiments.

5

The men had agreed that the cooling effects of blood transfusion could be very promising treatment for “extravagant” minds. At the time, humoral imbalances were still understood to lie at the root of madness. Each of the humors was associated with specific qualities and was sensitive to the influences of the seasons. Blood was considered hot and moist and was most abundant in the spring (which gives new meaning to the term “spring fever”). People who were sanguine by nature were seen as being high-energy, warmhearted, and easily prone to fits of anger. In contrast, black bile was cold and dry, and was most prolific in autumn. Melancholics were milder-mannered and had less energy than sanguine people. Yet their state could range from despondent to suicidal when they suffered from an overabundance of black bile in their bodies. The humors at once influenced and were influenced by human emotion. Heartbreak, stress, and anger could increase body temperature, which would create nox

ious vapors in the body that would rise to the brain and cause mental disturbances. The cures for mental illness were, then, very similar to those of any illness caused by humoral imbalance. In these cases bleedings were performed on the forehead or even on the hemorrhoidal veins in order to draw blood down and away from the brain. For “melancholy and mopish people,” cooling

mixtures of lapis lazuli, hellebore, cloves, or licorice powder were regularly infused in white wine and borage, again as an attempt to cool the humors and calm the mind.

6

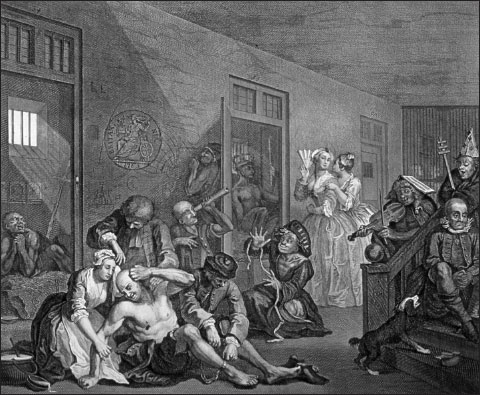

FIGURE 19:

Life at Bedlam depicted by William Hogarth in

A Rake's Progress

(1735). Some historians have suggested, and perhaps rightly so, that Hogarth may have exaggerated somewhat the conditions of Bethlem. Yet, it is worth noting that the Bedlam at the time of this painting was the more modern and spacious one built by Robert Hooke in 1670. Hogarth's images may just have beenâregrettablyâright on target for the period in which the Royal Society visited the hospital in search for the ideal patient.

Another more invasive procedure was often performed when humoral therapeutics proved ineffective. Doctors speculated in those cases that a foreign object lodged deep in the brain was the actual cause for the patient's odd behavior. The operation, performed with some regularity since the Middle Ages, involved boring a hole into the skull with a hand-cranked circular drill. Once the barber-surgeon made a sufficiently large hole in the patient's cranium, he would then probe the patient's brain in search of a pea-size “stone.”

For a Bedlamer skull-drilling might have seemed preferable to the procedure the Royal Society was imagining for its next patient. The fellows contacted Doctor Allen, manager of Bedlam, to see if he could recommend a patient well suited for an experimental blood transfusion. While we have no details about the conversation that may have transpired between the fellows and the doctor, there is little doubt that Allen refused to go along with the plan. Hooke, Clarke, Lower, and King met personally with the Bedlam head to persuade him to change his mind, without success. Given the inhumane conditions at the asylum, it does indeed seem odd that the physician would have refused on the grounds of patient safety. Yet blood transfusion was still so new and its effects still so dubious that Allen may have refused on ethical grounds. In the absence of historical documents regarding the details of Allen's meetings with the Royal Society fellows, we are left only to speculate.

The transfusionists would have to find another way to locate a suitable subject for their trial. If they were not able to procure a patient directly from Bedlam, they would look for someone who roamed freely through London but who had not yet been

committed to the hospital. It would not be a hard task. In the busy capital there were as many, if not more, mildly deranged people on the streets as there were within the walls of a single madhouse.

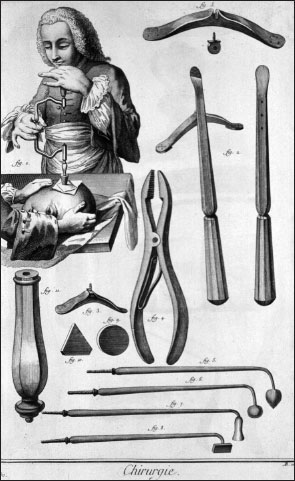

FIGURE 20:

Since the Middle Ages, trepanning was used as a way to relieve the symptoms of mental illness. This illustration shows the various tools that were used in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries for the procedure.

Encyclopédie

(1772).

The Royal Society committee soon learned from fellow member John Wilkins about a possible candidate. The thirty-two-year-old Arthur Coga attended Wilkins's church. Coga had studied at

Pembroke College, Cambridge, where his brother would eventually become a schoolmaster. Obviously well-educated and from a respectable family, Coga preferred to speak Latin, insisting on using it for any possible occasion. And that was not the only curious thing about him. There was something a little off about the man's behavior, but no one could put a finger on it. The only diagnosis that history has left us comes from Richard King, who explained simply to Boyle that Coga's “brain is sometimes a little too warm.” Oldenburg also acknowledged that Coga was “look't upon as a very freakish and extravagant manâ¦an indigent person.” His assessment was confirmed by Wilkins, who told Pepys during a drinking session in a London tavern that Coga was “a little franticâ¦a poor and a debauched man.”

7

The prevailing logic was that transfusion would help cure Coga of his illness by replacing his overheated blood with other, cooler blood. As such, he was the perfect candidate for the experiment that would put England back into the blood wars.