Blood Work (3 page)

Authors: Holly Tucker

Mauroy had been selected for the experiment because he was one of the most famous, or rather infamous, men in the tight-knit community of nobles living in the Marais. Most of the quarter's elite remembered him as the Marquise de Sévigné's perfectly mannered and well-dressed valet, the one who smiled with compassion as they nervously straightened their wigs or tugged at their corsets before entering the

salon

of the exacting marquise.

Now peals of laughter echoed throughout tastefully appointed reception halls as women in ribbon-decked dresses and men in wigs and flouncy cravats exchanged tales of Mauroy's exploits. According to one well-worn story, cavalry guards were making their nightly tour of the Marais. As their horses nipped down into the hay, munching and snorting, they awoke the naked Mauroy, who had settled into the bale for the night. He responded with bansheelike screams; the horses bolted, and the guards swore to anyone within earshot that they had been chased by the devil himself.

15

Montmor, Denis, and Emmerez felt certain that if they could cure Mauroy, they would soon become as legendary as their patient. And so it was, at six o'clock on that cold December evening in 1667, that the blood transfusion began. Lamps had been lit, and chaotic energy filled the air. A crowd of physicians and surgeons continued to stream into the roomâanxious for the show to begin. Pushing back the crowd, Emmerez first drew ten ounces of blood from Mauroy's right arm and then opened the calf's femoral artery. The madman's demands to be released competed with Montmor and Denis' angry shouts to the spectators to back up and quiet down. Emmerez swore as he was bumped and jostled; he was working diligently to unite the two transfusion tubes while trying to avoid a face full of blood. To no small frustration of the transfusion team, only five or six ounces of calf blood made it into the man. Yet Mauroy began to sweat profusely; his arm and both armpits were burning hot. The room began to spin around him.

While the men had no way of knowing this, Mauroy's immune system was launching an attack on the foreign antigens in the calf's blood. Typical symptoms of a hemolytic transfusion reaction include fever, chills, fainting, or dizziness, as well as bloody urine and back or side pain. They begin most often shortly after a

transfusion of incompatible blood, either from a human of a different blood group or, as in this case, another species. Antibodies produced by the recipient's immune system attack the donor cells and cause them to burst. The severity of the blood reaction depends on the amount of blood transfused, the rate at which it is transfused, and whether the patient has had previous exposure to the incompatible blood. Yet this knowledge of blood groups and their importance was still three hundred and thirty-four years in the future. It would not be until 1901 that Carl Landsteiner performed what was actually a very simple experiment and noticed clotting in some samples of mixed blood and not others. The Viennese doctor separated his samples into three groups: A, B, and C (what we now recognize as O), according to their clotting tendencies.

Landsteiner initially overlooked the group AB, which occurs in just 3 percent of populations. In 1907 two researchers working independentlyâJan Jansky in Czechoslovakia and William Lorenzo Moss in the United Statesâuncovered this fourth group. They used roman numerals (I, II, III, IV) to designate each blood group. Jansky classified what we now call group AB as IB, and Moss classified it as I. To avoid confusion the American Association of Immunologists adopted, in 1927, at Landsteiner's urging, the now-standard notation of A, B, AB, and O.

16

What the seventeenth-century doctors could know, however, was that if they did not stop the transfusion immediately, their patient would soon be dead. As Mauroy swooned, Emmerez ripped the small metal tube from his arm and closed up the wound as quickly as he could. The limp and pale man was helped to his feet and carefully accompanied to the servants' quarters to recover. When the room had finally cleared and the help had been called to clean up the calf's carcass and the bloody mess that went with it, all that could be heard were Mauroy's faint whistles

and insane rants echoing across the adjacent courtyard. But as the sun rose the next morning, Mauroy appeared to be somewhat less deranged than beforeâin fact, he seemed to be an altogether changed man.

Denis and Emmerez decided to tempt fate and try a second transfusion. The two men had persuaded Montmor to be more prudent with the guest list, which they limited to a much smaller, better-behaved, and more elite crowd of physicians. Two days later, again at precisely 6:00 p.m., a weakened and more docile Mauroy was led into the room. Barber's blade and bloodletting pan in hand, Emmerez could not find a vein in the right arm. The men speculated that this was no doubt the result of the toll that Mauroy's living conditions had taken on his body. Mauroy had suffered from months of homelessness, hunger, and cold; there was no possibility, they blindly concluded, that his condition could have been the consequence of the earlier experiment. The left arm proved more successful. Two ounces of blood were removed, and more than sixteen ounces of calf's blood took its placeânearly triple what had been transfused into Mauroy during the first experiment.

As soon as the blood began to enter Mauroy's veins, his pulse quickened. He began to sweat in the draft-filled wintry room. He cried that his kidneys hurt, that he was nauseous, that he would choke to death if he was not released from this experiment, this hell. Sensing that they might have gone too far, Denis ordered the tube connecting man to animal be removed. As Emmerez set to work closing the wound, the homeless man promptly vomited the “store of bacon and fat” he had gulped down shortly before and continued to purge “diverse liquors” until he passed out from exhaustion two hours later.

17

When Mauroy awoke the following morning, he was calm and alert. With uncharacteristic politeness, he requested that a

priest come to his bedside so he could confess his sins. After the confession Father Veau closed the door quietly behind him and paused to marvel out loud at what he had just seen. Mauroy was now of sound mind and would actually soon be fit to receive the Sacrament.

18

As Mauroy continued to rest under the watchful eye of the transfusionist, the madman's wife searched the streets for her missing husband. News of the transfusion had circulated throughout the city and into the countryside. The haggard and penniless woman soon found herself in a home she would never before have dared to enter. Perrine Mauroy slunk toward her husband with great trepidation. She winced as Mauroy leaped from his bed, and she looked surprised, very surprised, when he embraced her passionately. According to Denis' clearly self-interested account of the couple's interactions, Mauroy explained in great detail and “with great presence of mind” to his wife all that had happened to him since she had last seen him: his follies in the street, his naked rants, andâof courseâthe transfusions the “kind physician” had performed on him.

19

The wife turned, dumbfounded, toward Denis and stammered a quiet thank-you. At this time of the year and in this “full of the moon,” her husband should have been quite insane. Instead of the kindness he was now showing her, she whispered, he would have done nothing but swear and beat her. Madame Mauroy felt both relieved and reluctant to be again at her husband's side. When Denis finally released the former madman from his care, her reluctance turned to fear and dread. The couple returned to their modest, debt-ridden life on the outskirts of Paris. Perrine had spent several comfortable days among the rich and famous; now she found herself once more in poverty, frightenedâand wondering when her husband's anger would unleash itself anew.

While Perrine shuddered in fear, Denis proudly set himself to

announcing the details of his successes as broadly as possible. In the months that had preceeded this history-making experiment, the transfusionist had perfected his technique using a host of dogs, cows, sheep, and horses. His efforts paid off, and he reveled in the pleasure of his newfound celebrity. Yet it would soon be short-lived. Soon, Mauroy would be dead. And Denis would be staring down accusations of murder.

CIRCULATION

England, 1628â1665

I

f Denis had just made a name for himself as France's premier transfusionist, he had France's enemiesâthe Englishâto thank for it. For almost four decades English physicians and natural philosophers had tried to make sense of blood's mysteries. The results of their efforts had been stunning. In 1628 the Englishman William Harvey made a discovery that rocked the foundation of medical models that had endured unquestioned for nearly two millennia. His arguments that blood circulated through the body set off a flurry of experiments by men such as Christopher Wren, Richard Lower, Robert Boyle, and Robert Hooke. With each experiment, they took one step closer to attempting transfusions in humans.

In the seventeenth century, research on living humans was, even in the heady years surrounding the early race to perfect blood transfusion, still rare. Instead, medical exploration took place most frequently in the domain of death. Human dissectionsâwhich were conducted in university anatomical theaters, public gardens, and private homesâwere a regular feature of

European scientific and social life. While natural philosophers had occasionally been known to dissect newly defunct colleagues, their scalpels and saws were most often focused on executed criminals. Long seen as a punishment worse than death itself, the dissection of criminals was officially sanctioned by Pope Sixtus IV in 1482.

1

Fifty years later, in 1537, Pope Clement VII gave formal permission to include anatomical demonstrations, again on criminals, in medical school curricula.

On the mornings of hanging days the church bells rang to let Londoners know that a much-anticipated show was about to begin. Prisoners were led from their squalid cells at Newgate Prison to an “Execution Sermon” in the prison's drafty third-floor chapel. They were seatedâmen on one side, women on the otherâaround a coffin as they listened to a priest warn of hell and brimstone, repentance and forgiveness. Spectators, who paid handsomely for the chance to witness the last desperate moments of the condemned, were separated from the sinners by a low wall.

2

Some prisoners pleaded their innocence and begged for their lives. Others were contrite and pledged their souls to God in return for being spared. The most hardened of the “malefactors,” as they were called, spit proudly and swore with disdain at their confessors.

This dramatic prelude to the execution accomplished, the prisoners were then led away, shackled together at the ankles, to the open carts that would carry them to the gallows. Once aboard, sitting amid the rough-hewn coffins that housed their futures, they jostled against each other for room. Three long miles separated Newgate Prison from Tyburn, the infamous village where London had staged its executions since the early Middle Ages. A scaffold specially designed for mass executions awaited its next shipment of souls. The “Tyburn Tree” consisted of three posts that rose ten to twelve feet in the air. In an ingenious configuration that allowed multiple hangings at the same time, crossbeams

connected each of the posts. The most recent record for simultaneous hangings had been set in 1649, when twenty-three men and one woman swung together in a public spectacle.

3

And a spectacle it was. Tyburn attracted the city's underbelly. Families and coconspirators of convicted murderers, thieves, and rapists joined riotous crowds of cutpurses and prostitutes. Yet the most notorious players in this grotesque show were the corpse brokers who formed a league of vulture-like wheelers and dealers. They competed for access to fresh cadavers, which they would provide, at a good price, to London's various medical practitioners and medical schools.

William Harvey was one of the many men who covetously sought bodies for research. Harvey was so convinced ofâone might even say obsessed byâthe utility of dissection that there seemed barely a day that he did not have the body of a human or an animal splayed out in a state of half destruction on one of the large wooden tables in his home. Harvey's belief in “ocular demonstration,” as he called it, was relentless. And any corpse was fair game for his exploration. He is even said to have performed postmortems on his own father, sister, and a close friend.

4

Harvey was among those who argued that it was time to shrug off tradition and blind reliance on the wisdom of ancient writers whose theories had dictated medical practice for millennia. Such theories were not informed by firsthand observations of the inner structures of the human body: The lengthy medical treatises of such men as Hippocrates, Galen, and Aristotle were founded on interpolations made from their work on monkeys, pigs, and other animals. Deviating dramatically from these influential predecessors, Harvey, however, believed that any physician worth his salt had no choice but to roll up his sleeves and get his hands dirty in exploring the mysteries of the human body.

Before long Harvey was putting two thousand years' worth

of Galenic knowledge of the human heart and blood to the test. For the influential second-century physician Galen, blood did not circulate. Instead it made a one-way trip from the stomach to the heart. Venous blood, according to Galen, was the product of food that was “cooked” in the digestive tract and filtered in the liver. The blood coursed from the liver and toward the heart, where the fluid seeped through the heart's chambers through what was believed to be invisible porous membranes. Heat in the body was produced by the heart, whose primary responsibility was to burn blood like kindling in a furnace. Respiration was not, it was believed, responsible for oxygenating blood. Breathing was instead a means to blow off the “smoke” or fumes created by the heart's furnace.

This basic understanding of the heart's fires helps to explain early predilections for bloodletting as a first course of action in the event of illnessâand as a preventive measure. A fever was considered to be a sure sign of an overabundance of blood. After all, a well-stoked fire can easily turn into a bonfire if given too much wood or if doused with oil. And by the Middle Ages bloodletting had become the unquestioned first course of action for nearly every human ailment imaginable.

5

As one medieval physician wrote:

Phlebotomy clears the mind, strengthens the memory, cleanses the stomach, dries up the brain, warms the marrow, sharpens the hearing, stops tears, encourages discrimination [careful decision making], develops the senses, promotes digestion, produces a musical voice, dispels torpor, drives away anxiety, feeds the blood, rids it of poisonous matter, and brings long lifeâ¦. It eliminates rheumatic ailments, gets rid of pestilent diseases, cures pains, fevers and various sicknesses and makes the urine clean and clear.

6

Put more simply, bloodletting cured all. A belief in the “humors” lay at the heart of the early modern period's attachment to bloodletting. Following in the footsteps of Hippocrates, Galen offered an account of humoralist anatomy and physiology that dominated nearly every aspect of medical theory and practice from antiquity to the eighteenth century. Galenism held that the body was ruled by four different bodily fluids called “humors” and that each carried specific properties. Blood, phlegm, choler (yellow bile), and melancholy (black bile) mixed together in proportions that were specific to each individual. This humoral profile was called the “complexion.” Good health was the result of a complexion that was perfectly balanced. Illness descended when one or more humors were out of proportion. Purgings, through emetics and laxatives, gave the body the jump start it needed in order to shed unwholesome fluids and to regain necessary equilibrium.

For centuries blood was regularly coaxed out of bodies by barber-surgeons. The same men entrusted with close shaves and haircuts were also responsible for bloodletting, boil lancing, tooth pulling, and trepanning (skull drilling). They did not receive training in universities or through formalized study of booksâwhich were reserved for physicians who actually had little contact with patients in comparison. Barber-surgeons instead learned their trade through the trials and errors of apprenticeship. The instruments of barber-surgeons were crude; the more menacing tools consisted of saws used in amputations, plierlike devices to remove bullets, and hand-cranked drills for trepanning. And they were used under even cruder hygienic practices. Some barber-surgeons traveled with toolbox in hand, from home to home and from village to village. Others set up shop in more permanent locales, in small street-facing rooms. There was no need to hang a sign; the dripping red rags and barely rinsed pans outside were signal enough of the bloody work within. Modern-

day barbershops commemorate the early origins of the profession. Now quaint and certainly less macabre, metal-capped red-and-white-striped poles, displayed prominently outside barbers' doors, evoke the bloody bandages and bowls of earlier days.

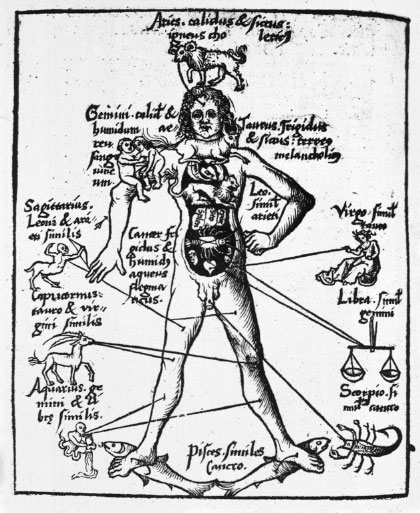

The toolboxes of local barber-surgeons included the prerequisite lancets, rags, straps, and blood bowls, but they also con

tained meticulous up-to-date plottings of the constellations. If health was related to the seasons, it was also related to the stars. Astronomy and astrologyâthe distinction between the two was not evident until the early eighteenth centuryâplayed an especially important role in bloodletting. While most bleeding was done from the forearm, bleeding charts showed the places of the body as they were governed by specific star signs. Folded almanacsâcalled “girdle books” because they were often tucked into beltsâdepicted the phases of the moon and dates of projected eclipses as well as conventional drawings of astrologically based bleeding points. The heart was connected to Leo; the feet, Pisces; the gut, Libra; and the genitalia, ever-amorous Scorpio. Any bleeding from the body part that matched the current star sign was ill advised. The ailment itself contributed another variable to the complicated calculus required for determining the exact location for bleeding. Writing in the sixteenth century, the celebrated military and court surgeon Ambroise Paré explained, for example, that “a vein of the right arm is to be opened to stay the bleeding of the left nostril” and “a vein is to be opened in the ankle to draw down the menstrual flow in women.”

7

FIGURE 1:

Zodiac Men, such as this one from Gregor Reisch's

Margarita philosophica

(1503), were used as easy-to-read guides for the optimal bleeding locations at specific moments of the year.

Another method of bloodletting included scarification followed by cupping. Using a multibladed lancet, the barber-surgeon made several shallow incisions close to one another. A small glass cup was heated in a fire and placed over the cuts. While the patient could count on a circular blister from the heat of the glass, the vacuum it created served to draw out the blood from the incisions. Leeches were, of course, another preferred tool for removing unwanted blood from the sick and dying. The trouble with leeches was that they were slimy and hard to control. And, as Paré explained, they could also be fickle. “If the leeches be handled with the bare hand,” Paré wrote, “they are angered, and become so stomachful as that they will not bite.” He recommended that

they be held instead in a white and clean linen cloth. To tempt the leeches to latch on, the patient's skin should be first lightly scarified or “besmeared with the blood of some other creature, for thus they will take hold of the flesh, together with the skin, more greedily and fully.” Salt and ash were used to coax the animals to let go, although they were usually left to feast on their hosts until they could imbibe no longer and detached of their own accord. Unlike surgical bloodletting, where bowls were used to catch the fluid and could be used for measurement, it was difficult to know with certainty how much a leech ingested. In these cases Paré made the following recommendations: “If any desire to know how much blood they have drawn, let him sprinkle them with salt made into powder, as soon as they are come off, for thus they will vomit up what blood soever they have sucked.”

8

Bloodletting fell slowly out of favor in the nineteenth century. The work of such men as Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister ushered in the new understanding that disease was caused by germs and not humors. Their theories were accompanied by a renewed emphasis on evidence-based research and practice. In 1835 the French doctor Pierre Charles Alexandre Louisâoften credited with sparking the development of epidemiology as a fieldâinterviewed more than two thousand patients at the Paris hospital La Pitié, recording their autopsies in cases of eventual death. He asked patients when they first became ill, how their disease progressed, and what treatment had been performed. He used this data to assess bloodletting and, while not condemning it entirely, concluded that the usefulness of the procedure was “much less than has been commonly believed.”

9

And by the beginning of the twentieth century, bloodletting had moved from a two-thousand-year-old universal intervention to an odd artifact of medical history.