Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin

Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1 - THE SOVIET FAMINES

CHAPTER 4 - MOLOTOV-RIBBENTROP EUROPE

CHAPTER 5 - THE ECONOMICS OF APOCALYPSE

CHAPTER 7 - HOLOCAUST AND REVENGE

CHAPTER 8 - THE NAZI DEATH FACTORIES

CHAPTER 9 - RESISTANCE AND INCINERATION

CHAPTER 10 - ETHNIC CLEANSINGS

CHAPTER 11 - STALINIST ANTI-SEMITISM

your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamit

Paul Celan

“Death Fugue”

Everything flows, everything changes.

You can’t board the same prison train twice.

Vasily Grossman

Everything Flows

A stranger drowned on the Black Sea alone

With no one to hear his prayers for forgiveness.

“Storm on the Black Sea”

Ukrainian traditional song

Whole cities disappear. In nature’s stead

Only a white shield to counter nonexistence.

Tomas Venclova

“The Shield of Achilles”

PREFACE: EUROPE

“Now we will live!” This is what the hungry little boy liked to say, as he toddled along the quiet roadside, or through the empty fields. But the food that he saw was only in his imagination. The wheat had all been taken away, in a heartless campaign of requisitions that began Europe’s era of mass killing. It was 1933, and Joseph Stalin was deliberately starving Soviet Ukraine. The little boy died, as did more than three million other people. “I will meet her,” said a young Soviet man of his wife, “under the ground.” He was right; he was shot after she was, and they were buried among the seven hundred thousand victims of Stalin’s Great Terror of 1937 and 1938. “They asked for my wedding ring, which I....” The Polish officer broke off his diary just before he was executed by the Soviet secret police in 1940. He was one of about two hundred thousand Polish citizens shot by the Soviets or the Germans at the beginning of the Second World War, while Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union jointly occupied his country. Late in 1941, an eleven-year-old Russian girl in Leningrad finished her own humble diary: “Only Tania is left.” Adolf Hitler had betrayed Stalin, her city was under siege by the Germans, and her family were among the four million Soviet citizens the Germans starved to death. The following summer, a twelve-year-old Jewish girl in Belarus wrote a last letter to her father: “I am saying good-bye to you before I die. I am so afraid of this death because they throw small children into the mass graves alive.” She was among the more than five million Jews gassed or shot by the Germans.

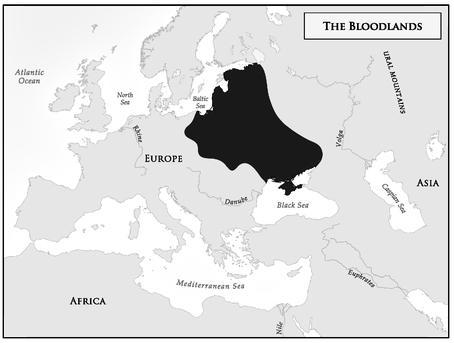

In the middle of Europe in the middle of the twentieth century, the Nazi and Soviet regimes murdered some fourteen million people. The place where all of the victims died, the bloodlands, extends from central Poland to western Russia, through Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic States. During the consolidation of National Socialism and Stalinism (1933-1938), the joint German-Soviet occupation of Poland (1939-1941), and then the German-Soviet war (1941-1945), mass violence of a sort never before seen in history was visited upon this region. The victims were chiefly Jews, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Poles, Russians, and Balts, the peoples native to these lands. The fourteen million were murdered over the course of only twelve years, between 1933 and 1945, while both Hitler and Stalin were in power. Though their homelands became battlefields midway through this period, these people were all victims of murderous policy rather than casualties of war. The Second World War was the most lethal conflict in history, and about half of the soldiers who perished on all of its battlefields all the world over died here, in this same region, in the bloodlands. Yet not a single one of the fourteen million murdered was a soldier on active duty. Most were women, children, and the aged; none were bearing weapons; many had been stripped of their possessions, including their clothes.

Auschwitz is the most familiar killing site of the bloodlands. Today Auschwitz stands for the Holocaust, and the Holocaust for the evil of a century. Yet the people registered as laborers at Auschwitz had a chance of surviving: thanks to the memoirs and novels written by survivors, its name is known. Far more Jews, most of them Polish Jews, were gassed in other German death factories where almost everyone died, and whose names are less often recalled: Treblinka, Chełmno, Sobibór, Bełżec. Still more Jews, Polish or Soviet or Baltic Jews, were shot over ditches and pits. Most of these Jews died near where they had lived, in occupied Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Soviet Ukraine, and Soviet Belarus. The Germans brought Jews from elsewhere to the bloodlands to be killed. Jews arrived by train to Auschwitz from Hungary, Czechoslovakia, France, the Netherlands, Greece, Belgium, Yugoslavia, Italy, and Norway. German Jews were deported to the cities of the bloodlands, to Łódź or Kaunas or Minsk or Warsaw, before being shot or gassed. The people who lived on the block where I am writing now, in the ninth district of Vienna, were deported to Auschwitz, Sobibór, Treblinka, and Riga: all in the bloodlands.

The German mass murder of Jews took place in occupied Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and the Soviet Union, not in Germany itself. Hitler was an anti-Semitic politician in a country with a small Jewish community. Jews were

fewer than one percent

of the German population when Hitler became chancellor in 1933, and

about one quarter of one percent

by the beginning of the Second World War. During the first six years of Hitler’s rule, German Jews were allowed (in humiliating and impoverishing circumstances) to emigrate. Most of the German Jews who saw Hitler win elections in 1933 died of natural causes. The murder of 165,000 German Jews was a ghastly crime in and of itself, but only a very small part of the tragedy of European Jews: fewer than three percent of the deaths of the Holocaust. Only when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939 and the Soviet Union in 1941 did Hitler’s visions of the elimination of Jews from Europe intersect with the two most significant populations of European Jews. His ambition to eliminate the Jews of Europe could be realized only in the parts of Europe where Jews lived.

The Holocaust overshadows German plans that envisioned even more killing. Hitler wanted not only to eradicate the Jews; he wanted also to destroy Poland and the Soviet Union as states, exterminate their ruling classes, and kill tens of millions of Slavs (Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Poles). If the German war against the USSR had gone as planned, thirty million civilians would have been starved in its first winter, and tens of millions more expelled, killed, assimilated, or enslaved thereafter. Though these plans were never realized, they supplied the moral premises of German occupation policy in the East. The Germans murdered about as many non-Jews as Jews during the war, chiefly by starving Soviet prisoners of war (more than three million) and residents of besieged cities (more than a million) or by shooting civilians in “reprisals” (the better part of a million, chiefly Belarusians and Poles).

The Soviet Union defeated Nazi Germany on the eastern front in the Second World War, thereby earning Stalin the gratitude of millions and a crucial part in the establishment of the postwar order in Europe. Yet Stalin’s own record of mass murder was almost as imposing as Hitler’s. Indeed, in times of peace it was far worse. In the name of defending and modernizing the Soviet Union, Stalin oversaw the starvation of millions and the shooting of three quarters of a million people in the 1930s. Stalin killed his own citizens no less efficiently than Hitler killed the citizens of other countries. Of the fourteen million people deliberately murdered in the bloodlands between 1933 and 1945, a third belong in the Soviet account.

This is a history of political mass murder. The fourteen million were all victims of a Soviet or Nazi killing policy, often of an interaction between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, but never casualties of the war between them. A quarter of them were killed before the Second World War even began. A further two hundred thousand died between 1939 and 1941, while Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union were remaking Europe as

allies

. The deaths of the fourteen million were sometimes projected in economic plans, or hastened by economic considerations, but were not caused by economic necessity in any strict sense. Stalin knew what would happen when he seized food from the starving peasants of Ukraine in 1933, just as Hitler knew what could be expected when he deprived Soviet prisoners of war of food eight years later. In both cases, more than three million people died. The hundreds of thousands of Soviet peasants and workers shot during the Great Terror in 1937 and 1938 were victims of express directives of Stalin, just as the millions of Jews shot and gassed between 1941 and 1945 were victims of an explicit policy of Hitler.

War did alter the balance of killing. In the 1930s, the Soviet Union was the only state in Europe carrying out policies of mass killing. Before the Second World War, in the first six and a half years after Hitler came to power, the Nazi regime killed no more than about ten thousand people. The Stalinist regime had already starved millions and shot the better part of a million. German policies of mass killing came to rival Soviet ones between 1939 and 1941, after Stalin allowed Hitler to begin a war. The Wehrmacht and the Red Army both attacked Poland in September 1939, German and Soviet diplomats signed a Treaty on Borders and Friendship, and German and Soviet forces occupied the country together for nearly two years. After the Germans expanded their empire to the west in 1940 by invading Norway, Denmark, the Low Countries, and France, the Soviets occupied and annexed Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and northeastern Romania. Both regimes shot educated Polish citizens in the tens of thousands and deported them in the hundreds of thousands. For Stalin, such mass repression was the continuation of old policies on new lands; for Hitler, it was a breakthrough.

The very worst of the killing began when Hitler betrayed Stalin and German forces crossed into the recently enlarged Soviet Union in June 1941. Although the Second World War began in September 1939 with the joint German-Soviet invasion of Poland, the tremendous majority of its killing followed that second eastern invasion. In Soviet Ukraine, Soviet Belarus, and the Leningrad district, lands where the Stalinist regime had starved and shot some four million people in the previous eight years, German forces managed to starve and shoot even more in half the time. Right after the invasion began, the Wehrmacht began to starve its Soviet prisoners, and special task forces called Einsatzgruppen began to shoot political enemies and Jews. Along with the German Order Police, the Waffen-SS, and the Wehrmacht, and with the participation of local auxiliary police and militias, the Einsatzgruppen began that summer to eliminate Jewish communities as such.