Bloody Crimes

Bloody Crimes

The Chase for Jefferson Davis and the Death Pageant for Lincoln’s Corpse

James L. Swanson

In memory of my mother, Dianne M. Swanson (1931–2008), who looked forward to this book but had no chance to read it.

In remembrance of John Hope Franklin (1915–2009), with gratitude for three decades of teaching, counsel, and friendship, and with fond memories of University of Chicago days.

Table of Contents

CHAPTER ONE “Flitting Shadows”

CHAPTER TWO “In the Days of Our Youth”

CHAPTER THREE “Unconquerable Hearts”

CHAPTER FOUR “Borne by Loving Hands”

CHAPTER FIVE “The Body of the President Embalmed!”

CHAPTER SIX “We Shall See and Know Our Friends in Heaven”

CHAPTER SEVEN “The Cause Is Not Yet Dead”

CHAPTER EIGHT “He Is Named for You”

CHAPTER NINE “ Coffin That Slowly Passes”

CHAPTER TEN “By God, You Are the Men We Are Looking For”

CHAPTER ELEVEN “Living in a Tomb”

CHAPTER TWELVE “The Shadow of the Confederacy”

| 1. | “Bloody Crimes” carte de visite of Columbia and her eagle | xiii |

| 2. | Senator Jefferson Davis on the eve of the Civil War | 4 |

| 3. | Fall of Richmond paper flag | 35 |

| 4. | Currier & Ives print of Richmond in flames | 40 |

| 5. | Abraham Lincoln oil portrait, as he appeared in 1865 | 43 |

| 6. | The Petersen House | 104 |

| 7. | Sketch of Lincoln on his deathbed | 112 |

| 8. | The empty bed, just after Lincoln died | 128 |

| 9. | Bloody pillow | 129 |

| 10. | “The President Is Dead” broadside | 132 |

| 11. | Diagram of the bullet’s path through Lincoln’s brain | 134 |

| 12. | The bullet that killed Lincoln | 135 |

| 13. | Allegorical print of Booth trapped inside the bullet | 137 |

| 14. | Portrait engraving of George Harrington | 142 |

| 15. | Invitation to Lincoln’s funeral | 187 |

| 16. | “Post Office Department” silk ribbon, April 19 funeral | 190 |

| 17. | Lincoln’s hearse, Washington, D.C. | 191 |

| 18. | Photograph of General E. D. Townsend | 203 |

| 19. | War Department pass for Lincoln funeral train | 207 |

| 20. | Lincoln’s funeral car | 211 |

| 21. | Silk mourning ribbon of the U.S. Military Railroad | 213 |

| 22. | President Lincoln’s hearse, Philadelphia | 221 |

| 23. | The New York funeral procession | 226 |

| 24. | Lincoln in coffin, New York City | 230 |

| 25. | Memorial arch, Sing Sing, New York | 233 |

| 26. | Viewing pavilion, Cleveland, Ohio | 253 |

| 27. | Terre Haute & Richmond Railroad timetable | 260 |

| 28. | Photograph of memorial arch, Chicago | 264 |

| 29. | Lincoln’s old law office; Springfield, May, 1865 | 272 |

| 30. | A map of the Abraham Lincoln funeral train route | 275 |

| 31. | Harper’s Weekly woodcut of burial in Springfield, Illinois | 283 |

| 32. | The first reward poster for Jefferson Davis | 297 |

| 33. | A map of Jefferson Davis’s escape route | 300 |

| 34. | Photograph of Davis in the suit he wore at capture | 310 |

| 35. | $360,000 reward poster for Davis | 319 |

| 36. | Three caricatures depicting Davis in a dress | 323 |

| 37. | The raglan, shawl, and spurs Davis wore on the day of capture | 328 |

| 38. | Print of Davis ridiculed in prison | 334 |

| 39. | Sketch of Davis in his cell | 335 |

| 40. | Lincoln’s home draped in bunting, May 24, 1865 | 339 |

| 41. | Davis as a caged hyena wearing a ladies’ bonnet | 343 |

| 42. | “The True Story…” print ridiculing Davis | 346 |

| 43. | Oil portrait of Jefferson Davis, ca. 1870s | 360 |

| 44. | Davis and family on their porch at Beauvoir, Mississippi | 362 |

| 45. | Oscar Wilde–inscribed photograph | 364 |

| 46. | Jefferson Davis late in life at Beauvoir | 377 |

| 47. | Davis lying in state, New Orleans, 1889 | 379 |

| 48. | A map of the Davis funeral train route | 380 |

| 49. | Davis’s New Orleans funeral procession, 1889 | 384 |

| 50. | Raleigh, North Carolina, floral display and procession, 1893 | 385 |

| 51. | The ghosts of Willie and Abraham haunting Mary Lincoln | 389 |

| 52. | Photographs of porcelain Lincoln memorial obelisk | 395 |

| 53. | The site of Jefferson Davis’s capture, near Irwinville, Georgia | 399 |

| 54. | Jefferson Davis’s library at Beauvoir, Mississippi | 403 |

M

y book

Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer

told the story of John Wilkes Booth’s incredible escape from the scene of his great crime at Ford’s Theatre and his run to ambush, death, and infamy at a Virginia tobacco barn. But the chase for Lincoln’s killer was not the only thrilling journey under way as the Civil War drew to a close in April 1865. While the hunt for Lincoln’s murderer transfixed the nation, two other men embarked on their own, no less dramatic, final journeys. One, Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, was on the run, desperate to save his family, his country, and his cause. The other, Abraham Lincoln, the recently assassinated president of the United States, was bound for a different destination: home, the grave, and everlasting glory.

The title of this book has three origins—as a prophecy, a promise, and an elegy.

In October 1859, abolitionist John Brown launched his doomed raid on the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, as a way of inciting a slave uprising. This daring but foolhardy attack, viewed as an

affront to the institution of slavery, enraged the South and brought the United States closer to irrepressible conflict and civil war. Following his capture, Brown was tried and sentenced to hang. While in a Charles Town jail awaiting execution, he was allowed to keep a copy of the King James Bible. As the clock ticked down to his hanging, Brown leafed through the sacred text, searching for divinely inspired words of justification, prophecy, and warning. He dog-eared the pages most dear to him and then highlighted key passages with pen and pencil marks, including this verse from Ezekiel 7:23: “Make a chain: for the land is full of bloody crimes, and the city is full of violence.” On the morning he was hanged, on December 2, 1859, he handed to one of his jailers the last note he would ever write: “I, John Brown, am now quite

certain

that the crimes of this

guilty land

will never be purged away but with

blood.”

On March 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address. Although remembered today for its message of peace—“with malice toward none, with charity for all”—the speech had a dark side. In a passage often overlooked, Lincoln warned that slavery was a bloody crime that might not be expunged without the shedding of more blood: “Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.’ ”

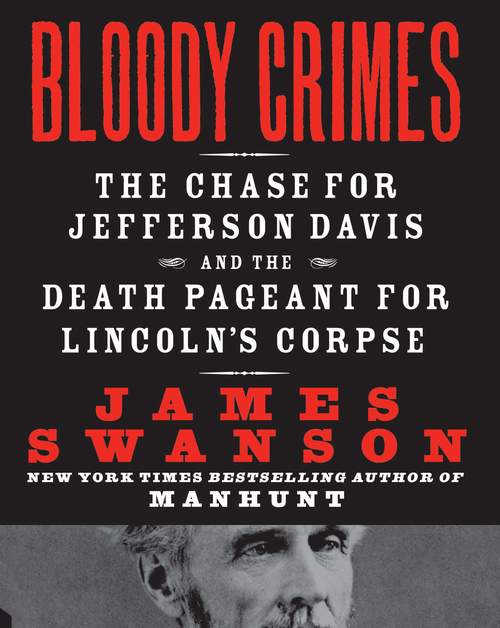

Within days of Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, a Boston photographer published a fantastical carte de visite image to honor the fallen president. That was not unusual; printers, photographers, and stationers across the country produced hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of ribbons, badges, broadsides, poems, and photographs to mourn Lincoln. But the image from Boston was different, for it expressed a sentiment not of mourning but of vengeance. In

“MAKE A CHAIN, FOR THE LAND IS FULL OF BLOODY CRIMES.”

this carte de visite, a stern-faced woman, crowned and draped as Columbia, accompanied by her servant, a screaming eagle about to take flight in pursuit of its prey, keeps a vigil over a portrait of the martyred president and echoes John Brown’s old warning: “Make a chain, for the land is full of bloody crimes.” Soon, in the aftermath of the chase for Jefferson Davis and the Lincoln assassination and death pageant, manacles and chains became symbols of the spring of 1865.

Northerners believed that Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy had committed many bloody crimes, including the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the torture, starvation, and murder of Union prisoners of war, and the battlefield slaughter of soldiers. In the South, Lincoln and his armies were seen as perpetrators, not victims, of great crimes. In the climate of these dueling accusations, the people of the Union and the Confederacy both shared a common belief and could agree upon one thing. In the spring of 1865, an era of bloody crimes had reached its climax.

The spring of 1865 was the most remarkable season in American history. It was a time to mourn the Civil War’s 620,000 dead and to bind up the nation’s wounds. It was a time to lay down arms, to tally plantations and cities that had been laid to waste, and to plant new crops. It was a time to ponder events that had come to pass and to look forward to those yet to be. It was the time of the hunt for Jefferson Davis and of the funeral pageant for Abraham Lincoln, each a martyr to his cause. And it was the time in America, wrote Walt Whitman, “when lilacs last in the door-yard bloom’d.”

WASHINGTON, D.C.

I

f you go there today, and walk to the most desolate corner of the cemetery, and then descend the half-hidden, decaying black slate steps, past all the other graves, down toward Rock Creek and the trees, you will find the tomb, now long empty. No sign remains that he was ever here. His name was never chiseled into the stone arch above the entry. But here, during the Civil War, in the winter of 1862, eleven-year-old Willie Lincoln, his father’s best-beloved son, was laid to rest. Here his ever-mourning father returned to visit him, to remember, and to weep. And here, the boy waited patiently behind the iron gates, locked inside the marble vault that looked no bigger than a child’s playhouse, for his father to claim him and carry him home.

That appointment, like his tiny coffin, was set in stone: March 4, 1869, the day Abraham Lincoln would complete his second term as president of the United States, leave Washington, and undertake the long railroad journey west, to Illinois. But in the spring of 1865,

in the first week of April, that homecoming seemed a long way off. President Lincoln still had so much more to do.

RICHMOND, VIRGINIA

If you visit his home today, you will find no sign that he ever left. The exterior of the house looks almost exactly like it does in the Civil War–era photographs. In his private office, documents still lie on his desk, as if awaiting his signature. His presidential oil portrait hangs on a wall. Maps chart the once mighty territorial expanse of the antebellum South’s proud agricultural empire. Books line the shelves. Children’s toys lie scattered across the floor. The house is furnished as it was April 2, 1865, the day he last walked out the door, never to return.