Blow Out the Moon (15 page)

Finally I heard a car in the distance slow down, and then saw it turn into the driveway. I got to the car before anyone got out.

“Mummy!” I shouted. “Mummy!”

Emmy made a little face at me (because of the “Mummy,” I knew).

I asked if I could show Emmy the horses, and my parents looked at each other. I had written to them about Nella that first day, and my riding lessons, but not about riding Tuppence.

“Oh, please can I?” she said.

“We’ll be very careful,” I said.

“Me come too?” Bubby said with a big smile, and we all laughed.

“You older girls may go if you promise to just look at the horses from over the fence: Don’t go into the field.”

We promised.

As soon as we could talk privately, Emmy looked at me and said,

“Mummy?”

“Well, that is how it’s pronounced in England,” I said. “We usually stand on the fence like this.”

I put my feet on the bottom rail and held the top one; Emmy did, too. We leaned over the fence and watched the horses eating grass in the sun. I told Emmy all their names, and about my riding lessons (I’d had several by then).

“It’s much harder than I thought it would be,” I said. “But I’m getting better: I can ALMOST post.”

I explained what posting was, and told her about riding Tuppence in the field that day, and she laughed, but when I asked her if she’d like to come to Sibton Park, too, she said no, she’d rather stay at home.

“If you came you could take riding lessons — we have three each week. And you could pet the horses whenever you wanted to,” I said. “I come into this field almost every day.”

Bubby in the back seat with her birthday teddy.

“It’s good — but, I don’t want to leave home,” Emmy said.

When we got into the car, Bubby proudly showed me her new teddy bear (it was almost as big as she was).

“My birthday teddy,” she said. “I’m three.”

She DID seem older. She seemed like a person, not a baby.

A lot of other things had changed at home, too. Jill was gone, they had moved (which I knew from my mother’s letters), but my father told me anyway, adding, “The new apartment has a big garden the children can play in.”

“Do you play in it?” I said.

“Sometimes,” Emmy said.

Bubby and Willy didn’t answer: They were talking to each other (or her new teddy and his old Raggedy Ann doll) in growly, very low voices and giggling, as usual. THAT hadn’t changed.

Willy and Bubby in the back seat.

We went to an inn for lunch and ate in the garden, until it started to rain heavily. That happened a lot on English outings.

The first part of lunch at the inn. You can only see a little of Emmy — she’s sitting between Willy and my mother, across the table from me.

After lunch, we drove back. Emmy wanted to go see the horses again, and I wanted to show them to Bubby and Willy, too; but it was time for them to go home and for me to be back at school, my father said.

I hugged him, and my mother, and Bubby, and Willy, and Emmy; and then they drove away. Emmy waved her arm back and forth across the whole rear window — I could see the gray sleeve of her sweater going back and forth until the car went out of sight.

“That Was My Father’s Legion”

“You’re awfully quiet today,” Matron said at lunch the next day.

I still sat next to her at meals; everyone else wanted to sit next to her, too, so they took turns sitting on her other side. To make it fair, everyone but me sat in the same order and at each meal, they all moved one place — like at the Mad Tea Party in

Alice in Wonderland.

I liked Matron as much as everyone else did, maybe more! But I didn’t like

having

to sit next to her because of my manners. I wanted to be able to eat the way everyone else ate.

“I’m concentrating on eating properly,” I said. Soup you had to tilt into your mouth, with the spoon sideways. Only the very edge of the spoon could touch your lips.

Matron laughed.

“But that’s no good! You must carry on a conversation

and

eat properly.” It was like riding, I thought: everything all at the same time. “Tell us where the Koponens are going for the summer holidays.”

That’s what they had been talking about: where everyone was going for the holidays. Matron’s parents and Clare were all going to Greece.

“To a farm in Cornwall for part of the time,” I said. “They’re not sure about the rest of the holidays. My father wants to take my mother to Italy, but they haven’t found a new nanny yet, so there’s no one to take care of us.”

“I’ll look after you!” Matron said eagerly.

I was VERY surprised — and pleased.

“I’ll write and ask!” I said. “Oh, I hope they say yes!”

Clare and I talked about it while we stood on line for sweets and walked to the Lower Garden, where we had a story after lunch. Miss Davenport was already sitting in her chair under the old oak, waiting while everyone found places on the grass.

Sun coming through leaves made little wavering patches of light and shadows on the lawn. And it was so bright and sunny that when I sat down, even the grass felt warm! I looked up at the big branch high above us, then around the lawn, at the dappled light and all the girls in their striped summer dresses: white with pale blue stripes, white with pale pink, white with pale green — they all looked white in the pale bright sun. When everyone was still and quiet, Miss Davenport began to read.

It was a happy feeling, looking at the dappled light, listening to the story. It was about an English boy in ancient Britain, and I liked it until a grown-up in the book told about a Roman legion that marched off into the mist and never came back. They just disappeared. There was a pause and the boy said, “That was my father’s legion.”

I imagined him just standing there, watching his father’s legion leave: men in tunics and metal helmets marching straight down a Roman road. That was the last time the boy ever saw his father — his father disappeared into the gray mist and never came back.

I saw that so clearly in my mind that I was almost surprised to look around me and see the old tree, the dappled light on the lawn, the faded pink house — surprised and glad. The old bricks’ colors were soft and peaceful — beautiful, even — glowing in the sun. They’d been there for hundreds and hundreds of years. They were solid and safe.

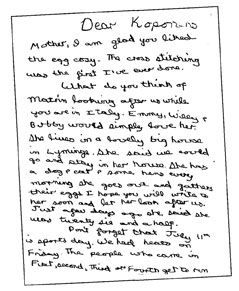

The letter I wrote asking about staying with Matron.

After Lights Out

The days got longer and longer: in England, the sky stays light almost all night in summer. When we went to bed it was still bright blue. The seniors had Lights Out much later — they were still outside when the sky had turned a strange silvery-white color and we were sitting up in bed, talking. If there was a pause in our conversation, we could hear them.

One night we talked, first about our running heats (we were practicing for Sports Day), and then about the Tennis Match. Juniors didn’t play tennis, but we’d all watched it, the whole school had. The look on the loser’s face was awful — and the loser was Jill, Buffer’s twin sister.

“Buffer didn’t even say anything to her,” Veryan said.

“She didn’t the day the seniors got their exams back, either,” Clare said, sounding even more critical.

I remembered Buffer running up the back stairs two at a time, so fast that she was putting her hands on the steps ahead of her, laughing and screaming: “I pahssed! I pahssed!”

Jill had not passed. She spent the whole afternoon crying in Alice and Tina’s room, being comforted by them — and Buffer ignored her.

“I hated Buffer that day,” Veryan said.

“So did I,” Brioney said.

“She was selfish,” said Clare.

I didn’t hate Buffer, but I did remember how the other seniors had acted. Alice and Tina passed, everyone knew they would; I don’t think anyone even asked them. Someone asked two other seniors if they’d passed. One looked a little embarrassed — as if she hadn’t really deserved to — and said yes. The other smiled, trying to be casual, but you could tell she was pleased. Only Buffer ran around screaming and laughing and telling people who hadn’t even asked her. I understood that you shouldn’t behave like that, ever; but I didn’t know if Jill being her own twin made it worse. I was wondering about that when we heard Matron laughing outside (of course, the windows were all open).

We all went to the same window and looked out. Miss Davenport and Matron were riding in the big meadow that sloped up to a skyline of trees. The sky was that strange light silvery color — not like day, but not like night, either — and their horses, Nella and Nike, looked silvery-white, too.

Suddenly Matron leaned forward in the saddle and shook her head, and first Nella, then Nike, GALLOPED towards the top of the meadow, stretching out their necks and tails while Matron shrieked with laughter.

Matron’s laugh got fainter and fainter as they raced farther and farther away, the horses’ tails streaming behind them.

We stood close together, watching. No one talked until we couldn’t see them anymore and were slowly getting back into bed.

“I didn’t know Matron rode,” Clare said quietly.

I hadn’t, either. I listened for Matron and the horses while the room grew dimmer; on the towel rack, I could see the white part of my towel, but not the colors of its gray and red stripes. I listened hard, but the only sounds were some seniors playing tennis: a ball being hit, someone calling “BAD luck!” and a piano — probably other seniors were rehearsing the play. None of us were in that (only one junior, a four-year-old day girl, was), and suddenly I had the idea of putting on our own play. ONLY the Night Nursery would be in it and we’d make it up ourselves.

In the morning I told the others, and everyone wanted to do it. In bed that night, we decided to make the play about doctors and nurses falling in love with each other (this, I admit, was kind of copied from an English TV show). The first thing we made up was a song about them falling in love, which Brioney and Clare and Veryan sang in American accents, one verse each. I just hummed the chorus.

Veryan made up a song to sing by herself. Her idea was that she would march down the aisle, dressed in a bride’s outfit, filing her nails with the file from my manicure kit, singing: