Blow the House Down

This author is available for select readings and lectures. To inquire about a possible appearance, please contact the Random House Speakers Bureau at

[email protected]

or (212) 572-2013.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Terry Anderson's

Den of Lions;

Lawrence Martin Jenco's

Bound to Forgive;

the 9/11 Commission Report; Murray Weiss's biography of John O'Neill,

The Man Who Warned America;

Many Rivers Films, who arranged for me to get into Israel's high-security prison; and my editor at Crown, Rick Horgan, who patiently kept this book on track.

PROLOGUE

Y

EARS LATER,

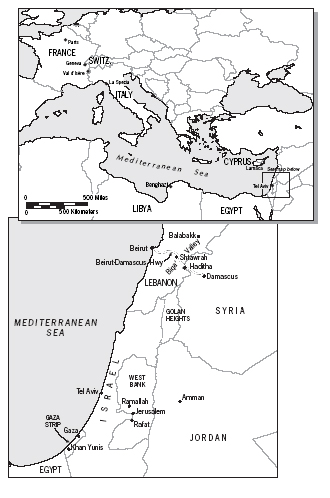

after the unthinkable happened, I would remember where I was when it all started: in a car on the Beirut-Damascus highway, still a young man who believed the good guys always won and with no idea that the colleague I was trying to contact on the radio was already facing his executioner.

“Carson, Carson, this is Lone Wolf. Over.”

Damn, still no answer.

“Carson” was Buckley's radio call signâBill Buckley, the CIA chief of station in Beirut. It was March 16, 1984, and I had a meeting with him at elevenâone I wasn't going to make. There'd been a firefight earlier that morning in Aley, and a Druze militia checkpoint was backing up traffic.

Bill wouldn't be surprised. Long ago he'd gotten used to my not being where I was supposed to be, operating solo, disappearing for days at a time, dragging in who knows what.

When Bill had me come work for him in Beirut in 1983, he assigned me the radio call sign “Lone Wolf.” Everybody else had towns in Nevada. The nickname stuck.

“Anyone copy? This is Lone Wolf.”

Someone finally keyed a radio. I heard static; then Art, the commo chief, came up on the net: “Lone Wolf, get off net immediately. Return to Reno ASAP.”

I switched off my Motorola, wondering what the fuck was going on.

Only when I got into the station did I learn Buckley had been kidnapped two hours earlier.

Â

Bill left the house every day at exactly twenty to eight, and that morning had been no different. He took the elevator to the ground-floor garage, where he checked carefully underneath his car for a bomb before starting the engine, because while Bill was regular, he was also cautious, and the Honda's underside had no armor. Satisfied, he backed out of his parking spaceâthe same space every dayâand started for the garage exit.

My guess is that Bill looked in his rearview mirror that morning and saw a car blocking his Honda. He got out to see what the problem was. Someone grabbed him from behind, hit him with something hard on the back of the head, threw him in the rear of the other car, covered him with a blanket, and tore off. Brutally efficient speed, surprise, and force. That's how I would have done it. There were no witnesses. All we had to go by was the open car door.

Getting Bill back was all the station cared about. But trying to survive ate up most of our time. We were operating at something like a 75 percent casualty rateâlosing people and assets faster than we ever did in Vietnam or Laos. Washington wasn't calling it a hot war, but that's what it was.

Then, in July 1985, we picked up chatter that the “big crate was broken.” In the shadow world of intercepts, our best guess was that the big crate was Bill. There were other hostages, but Bill was the most valuable to his captors. No one was ready to sign Bill's death certificate yet, but it was hard to maintain the fiction he was coming back.

One report with the ring of authenticity had it that Bill had been grabbed by a Sepah-i Pasdaran colonel who went by the name of Murtaza Ali Mousavi. (Sepah-i Pasdaran is shorthand for Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the spearhead of the Islamic revolution that Ayatollah Khomeini wanted to spread across the Middle East.) A couple low-level informants told us that an Iranian by that name had recruited the suicide bomber who drove an explosive-packed GMC pickup truck into the lobby of our embassy in Beirut. One bizarre description had him looking almost Westernâblue eyes and reddish hair. Mousavi also supposedly recruited the suicide bomber who drove a truck into the Marine barracks near the airport.

There were rumors, too, that Mousavi might be behind a particularly inventive monstrosity. At the peak of the Lebanese civil war, the Christian militia started finding their people dumped near the port with small holes drilled through their foreheads. What they eventually came to believe was that a sadistic dentist had been anesthetizing the victims' foreheads, drilling the holes, then sucking out their brains with an aspirator, one of those things dentists use to keep patients' mouth dry while they're working. I asked around and was assured a dentist's aspirator couldn't suck out a brain.

Maybe,

though, with a stiff suction probe.

The hard part came when we tried to put some meat on the name. We had no stable indices on Mousaviâno birth certificate, address, phone number, even a photo. One of our few leads came from Father Martin Jenco, the Catholic priest who had been kidnapped in Beirut in January 1985 and held for more than a year and a half, at least part of that time in the same apartment with Buckley. During his debriefing, Father Jenco told us that when his blindfold fell off one day he found himself face-to-face with one of his captors: a man with blue eyes and red hair, the Western features we'd heard about before. Father Jenco also thought the same captor might have been the one who spoke fluent EnglishâAmerican English complete with slang. But he couldn't be sure because of the blindfold. Were they one and the same, and was that person Colonel Mousavi?

I recruited a young Lebanese Shia from Beirut's southern suburbs who thought he could get inside Mousavi's network, maybe even tell us whether he really did have red hair and blue eyes. The kid had gotten caught up in the Islamic resistance against the Israelis. By the time I met him, he wanted out. He set about cultivating Mousavi's people, and I met him every two weeks at the Museum Crossing on the “Green Line,” the no-man's-land between Christian East Beirut and Muslim West Beirut, the safest place in Lebanon back then.

At one point when the kid was rummaging around in a safe house, he came across a Motorola radio and had the smarts to copy down the serial number. It matched Bill's Motorolaâthe same one I tried to call him on the day he disappeared.

The kid hadn't gotten far enough inside the network to meet Mousavi and confirm hair and eye color, but as much as there was any certainty in Lebanon, the kid was it. Then, one morning a Lebanese police officer on duty at the Museum Crossing called to say they'd just found the body of a young man. He had a small card in his shirt pocket with my name printed on it. Otherwise there was no identification. Did I know anything about him?

I did, of course, and as soon as I saw the quarter-inch hole drilled in the kid's forehead, I knew how he'd died. I was now convinced the dentist was real, and just maybe Murtaza Ali Mousavi too.

Â

I didn't report any of this to headquarters. You start sending back gruesome details like aspirated brains or betray any hint of an obsession, and they pull you out on a wack-a-vac and send you to some clinic for deprogramming.

But I kept pushing and soon after we picked up a lead that Mousavi's group was operating off a low-power, push-to-talk radio net. Our regular signal intelligence sites couldn't pick it up, so I talked the station into renting an apartment overlooking the Shia southern suburbs to see what I could find on a scanner. After a couple weeks listening, I came across an interesting net. Everyone on it used call signs and coded names, places, and times.

I taped all the important intercepts and wrote down everything I thought might matter. Telephone numbers, addresses, and namesâall went in my spiral notebooks. After six months I'd filled three of them. That's when we got the break I thought might crack everything open.

Another informantâa good oneâtold us that until the start of the revolt against the Shah, the elusive colonel had been a Ph.D. candidate in mathematics at UCLA. Later, we heard much the same from Terry Anderson, another hostage held with Buckley: Not only did his captor claim to have attended UCLA and the American University of Beirut, but he had a strange accentâalmost American but with a peculiar rolling

R

as if he'd learned French before English. “Sounds more Iranian than Lebanese,” Anderson said.

We immediately checked all the visa and immigration records, but there was no indication that Mousavi had ever applied for or received a visa, either in Beirut or Tehran. I got a friend in the FBI's Los Angeles field office to run out to UCLA. He came up empty on the name, but an FBI informant did remember a French-educated Iranian studying there in the early seventies. He had been writing a dissertation on a subset of non-Riemannian hypersquares, whatever that is, until he dropped out of the program, short of a Ph.D.

When the registrar pulled up the records for my FBI pal, the Iranian student's name was missingâdigitally stripped out. The paper application, along with a photo, was gone, too. The registrar had never seen anything like it before. The only useful lead came from a professor in the mathematics department: He recalled a brilliant Iranian graduate student who had “sort of rusty hair.” But since the student was a loner and never showed up for lectures, he couldn't tell us much more.

I had been transferred out of Beirut when in late 1991 Bill Buckley's headless, decomposed body was found dumped like a dead dog in Beirut's southern suburbs.

Â

Confirmation that Bill was dead didn't diminish my interest in finding his kidnapperâif anything, it heightened it. But I wasn't in a position to do much about it until my many sins finally caught up with me, and I was yanked out of the field in January 2000 and brought back early to Langley to die a slow bureaucratic death. I was sure the trail had gone cold by then, but I started going through the databases anyhow, and eventually I found a reference to a photo of an “Ali Mousavi,” taken in Peshawar, Pakistan, archived to an inactive informant's file. It was a long shot, but I ordered the file from Archives.

It turned out to be harder than it should have been. Archives said they couldn't find the file, so I took the day off to look myself. I never did find it, but I finally turned up the photo: a posed shot of five people standing in a garden. Behind them was a cinder-block house with a couple of half-dead bushes and a barbecue pit. In the middle was Osama bin Laden, clutching what looked like a Koran in his hand. To the left of bin Laden was someone in a salwar chemise. Something about him, his hands maybe, suggested that he was Caucasian, a Westerner, but his head had been carefully scissored out. To bin Laden's right stood a young man in a galabiyah. He couldn't have been more than sixteen or seventeen. On the far right another young Arab wore a kafiyah and held up an AK-47, partly covering his face.

What really got my attention was the person on the far left of the photo: a slight man, maybe five-six, dressed in a rumpled polo shirt and jeans. He looked aloof, as if he were uncomfortable being there or having his photo taken. He was also the only one whose features were too defined to be Arab. Since the photo wasn't in color and the resolution was lousy, I couldn't be sure, but his hair was something other than jet-black. The absence of any caption didn't help either, but I had a hunch I'd never been closer to the Murtaza Ali Mousavi I had been following for fifteen years.

What I couldn't understand, if this was Mousavi, was what he would be doing with Osama bin Laden? If there was any constant in the Middle East, it was that Shia Muslims like Mousavi detested Sunni Muslims, especially uncompromising Sunnis like bin Laden, who considered all Shia heretics best put to the scimitar.

The headless somebody was also an anomaly. For a start, the salwar chemise was caved in, the way clothes are on very old or very sick people. That his head was missing wasn't all that unusual. Faces and other identifiers of CIA officers get cropped out of photos sent in from the field, even when they're marked

Secret.

But the chances of this guy being CIA were close to zero. None of our officers was ever in touch with bin Laden, in spite of the silly myth that he was the CIA's creation. So who was the headless horseman? And who were the other two young Arabs? The picture was intriguing, but it was getting me nowhere.

I needed someone to identify the players. If the dating on the photo was right, John Millis was in Peshawar when it was taken. John had since gone on to become chief of staff at the House Intelligence Committee. I gave him a call.

We met at the Tune Inn, a dive on Pennsylvania Avenue a few blocks from the Capitolâme in a pair of faded khakis and a tattered, wrinkled blue oxford shirt and Millis in his Joseph A. Bank, all-season, light wool suit. We were as mismatched as you get in Washington.

After the waitress brought us our burgers and coffees, Millis pulled the photo out of the manila envelope and took a close look at it.

“I used to walk by that house,” he said with a smile. “That's where bin Laden lived. I'd see him out front from time to timeâhad the impression he was friendly. Where'd you get this picture?”

“I thought you'd tell me. It was sent in from Peshawar when you were chief.”

“I don't remember it.”

“See anyone else you recognize there?”

“I don't know. Looks like the normal crazies who washed up in Peshawar in those days.”

Millis pulled a pair of fold-up reading glasses out of a sleek metal case, fitted them carefully to his ears, and took a closer look. When he was through, he held the photo to one side so I could see and began pointing, starting with the guy to the right of bin Laden.

“This one was a Gulf prince, a true believer who took up digs with bin Laden. He couldn't have been more than twenty. And this⦔ He stopped, held the photo closer, then held it out again so I could see. “This guy on the far right you should know.”

“I should?”

I tried to imagine whoever it was without his head wrap, without the AK-47 muzzle blocking half his face, minus the two-week-old stubble.

“A Palestinian,” Millis was saying. “He was with bin Laden, and then ended up in Hamas. Nabil something.”

I saw it then: Nabil Shahadah. After Afghanistan, he'd gone on to head up the military wing of Hamas. Nabil was the architect of the first suicide bus bombings in Israel, a lord of mayhem.

“And the headless guy? Was he ours?”