Blue Highways (30 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

“The mountain caused that.” I got up. “What do you mean by ‘taste’?”

“I’ll show you.”

We went to his dormitory room. Other than several Kachina dolls he had carved from cottonwood and a picture of a Sioux warrior, it was just another collegiate dorm room—maybe cleaner than most. He pulled a shoebox from under his bed and opened it carefully. I must have been watching a little wide-eyed because he said, “It isn’t live rattlesnakes.” From the box he took a long cylinder wrapped in waxed paper and held it as if trying not to touch it. “Will you eat this? It’s very special.” He was smiling. “If you won’t, I can’t share the old Hopi Way with you.”

“Okay, but if it’s dried scorpions, I’m going to speak with a forked tongue.”

“Open your hands.” He unwrapped the cylinder and ever so gently laid across my palms an airy tube the color of a thunderhead. It was about ten inches long and an inch in diameter. “There you go,” he said.

“You first.”

“I’m not having any right now.”

So I bit the end off the blue-gray tube. It was many intricately rolled layers of something with less substance than butterfly wings. The bite crumbled to flakes that stuck to my lips. “Now tell me what I’m eating.”

“Do you like it?”

“I think so. Except it disappears like cotton candy just as I get ready to chew. But I think I taste corn and maybe ashes.”

“Hopis were eating that before horses came to America. It’s piki. Hopi bread you might say. Made from blue-corn flour and ashes from greasewood or sagebrush. Baked on an oiled stone by my mother. She sends piki every so often. It takes time and great skill to make. We call it Hopi cornflakes.”

“Unbelievably thin.” I laid a piece on a page of his chemistry book. The words showed through.

“We consider corn our mother. The blue variety is what you might call our compass—wherever it grows, we can go. Blue corn directed our migrations. Navajos cultivate a yellow species that’s soft and easy to grind, but ours is hard. You plant it much deeper than other corns, and it survives where they would die. It’s a genetic variant the Hopi developed.”

“Why is it blue? That must be symbolic.”

“We like the color blue. Corn’s our most important ritual ingredient.”

“The piki’s good, but it’s making me thirsty. Where’s a water fountain?”

When I came back from the fountain, Fritz said, “I’ll tell you what I think the heart of our religion is—it’s the Four Worlds.”

Over the next hour, he talked about the Hopi Way, and showed pictures and passages from

Book of the Hopi

. The key seemed to be emergence. Carved in a rock near the village of Shipolovi is the ancient symbol for it:

With variations, the symbol appears among other Indians of the Americas. Its lines represent the course a person follows on his “road of life” as he passes through birth, death, rebirth. Human existence is essentially a series of journeys, and the emergence symbol is a kind of map of the wandering soul, an image of a process; but it is also, like most Hopi symbols and ceremonies, a reminder of cosmic patterns that all human beings move in.

The Hopi believes mankind has evolved through four worlds: the first a shadowy realm of contentment; the second a place so comfortable the people forgot where they had come from and began worshipping material goods. The third world was a pleasant land too, but the people, bewildered by their past and fearful for their future, thought only of their own earthly plans. At last, the Spider Grandmother, who oversees the emergences, told them: “You have forgotten what you should have remembered, and now you have to leave this place. Things will be harder.” In the fourth and present world, life is difficult for mankind, and he struggles to remember his source because materialism and selfishness block a greater vision. The newly born infant comes into the fourth world with the door of his mind open (evident in the cranial soft spot), but as he ages, the door closes and he must work at remaining receptive to the great forces. A human being’s grandest task is to keep from breaking with things outside himself.

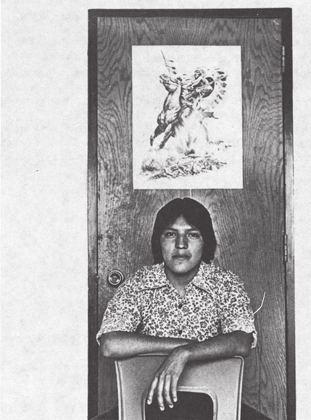

12. Kendrick Fritz in Cedar City, Utah

“A Hopi learns that he belongs to two families,” Fritz said, “his natural clan and that of all things. As he gets older, he’s supposed to move closer to the greater family. In the Hopi Way, each person tries to recognize his part in the whole.”

“At breakfast you said you hunted rabbits and pigeons and robins, but I don’t see how you can shoot a bird if you believe in the union of life.”

“A Hopi hunter asks the animal to forgive him for killing it. Only life can feed life. The robin knows that.”

“How does robin taste, by the way?”

“Tastes good.”

“The religion doesn’t seem to have much of an ethical code.”

“It’s there. We watch what the Kachinas say and do. But the Spider Grandmother did give two rules. To all men, not just Hopis. If you look at them, they cover everything. She said, ‘Don’t go around hurting each other,’ and she said, ‘Try to understand things.’”

“I like them. I like them very much.”

“Our religion keeps reminding us that we aren’t just will and thoughts. We’re also sand and wind and thunder. Rain. The seasons. All those things. You learn to respect everything because you

are

everything. If you respect yourself, you respect all things. That’s why we have so many songs of creation to remind us where we came from. If the fourth world forgets that, we’ll disappear in the wilderness like the third world, where people decided they had created themselves.”

“Pride’s the deadliest of the Seven Deadly Sins in old Christian theology.”

“It’s

kahopi

to set yourself above things. It causes divisions.”

Fritz had to go to class. As we walked across campus, I said, “I guess it’s hard to be a Hopi in Cedar City—especially if you’re studying biochemistry.”

“It’s hard to be a Hopi anywhere.”

“I mean, difficult to carry your Hopi heritage into a world as technological as medicine is.”

“Heritage? My heritage is the Hopi Way, and that’s a way of the spirit. Spirit can go anywhere. In fact, it has to go places so it can change and emerge like in the migrations. That’s the whole idea.”

A

THIRD

of the land mass of earth is desert of one kind or another. After my bout with the mountain, I found that a comforting statistic as I started across the Escalante Desert west of Cedar City. Utah 56 went at the sagebrush flats seriously, taking up big stretches before turning away from anything.

A car whipped past, the driver eating and a passenger clicking a camera. Moving without going anywhere, taking a trip instead of making one. I laughed at the absurdity of the photographs and then realized I, too, was rolling effortlessly along, turning the windshield into a movie screen in which I, the viewer, did the moving while the subject held still. That was the temptation of the American highway, of the American vacation (from the Latin

vacare,

“to be empty”). A woman in Texas had told me that she often threatened to write a book about her family vacations. Her title:

Zoom!

The drama of their trips, she said, occurred on the inside of the windshield with one family crisis after another. Her husband drove a thousand miles, much of it with his right arm over the backseat to hold down one of the children. She said, “Our vacations take us.”

She longed for the true journey of an Odysseus or Ishmael or Gulliver or even a Dorothy of Kansas, wherein passage through space and time becomes only a metaphor of a movement through the interior of being. A true journey, no matter how long the travel takes, has no end. What’s more, as John le Carré, in speaking of the journey of death, said, “Nothing ever bridged the gulf between the man who went and the man who stayed behind.”

Within a mile of the Nevada stateline, the rabbit brush and sage stopped and a juniper forest began as the road ascended into cooler air. I was struck, as I had been many times, by the way land changes its character within a mile or two of a stateline. I turned north on U.S. 93, an empty highway running from Canada nearly to Mexico. I’m just guessing, but, for its great length, it must have fewer towns per mile than any other federal highway in the country. It goes, for example, the length of Nevada, more than five hundred miles, passing through only seventeen towns—and that’s counting Jackpot and Contact.

Pioche, one of the seventeen, was pure Nevada. Its elevation of six thousand feet was ten times its population; but during the peak of the mining boom a century ago, the people and the feet above sea level came to the same number. The story of Pioche repeats itself over Nevada: Indian shows prospector a mountain full of metal; prospector strikes bonanza; town booms for a couple of decades with the four “G’s”: grubstakes, gamblers, girls, gunmen (seventy-five people died in Pioche before anyone died a natural death); town withers. By 1900, Pioche was on its way to becoming a ghost town like Midas, Wonder, Bullion, Cornucopia. But, even with the silver and gold gone, technological changes in the forties made deposits of lead and zinc valuable, and cheap power from Boulder Dam (as it was then) kept Pioche alive.

A citizen boasted to me about their “Million Dollar Courthouse”—a plain yet pleasing century-old fieldstone building sitting high on the mountainside—albeit a little cynically, since construction cost a fraction of that; but through compound interest and refinancing, the price finally hit a million. The courthouse was condemned three years before the mortgage was paid off.

The highway went down into a narrow and immensely long, thunder-of-hooves valley, then, like a chalkline, headed north, running between two low mountain ranges, the higher eastern one still in snow. A sign:

NEXT GAS 80 MILES.

In the dusk, the valley showed no evidence of man other than wire fences, highway, and occasional deer-crossing signs that looked like medieval heraldic devices: on a field of ochre, a stag rampant, sable. The signs had been turned into colanders by gunners, almost none of whom hit the upreared bucks.

Squat clumps of white sage, wet from a shower out of the western range, sweetened the air, and gulches had not yet emptied. Calm lay over the uncluttered openness, and a damp wind blew everything clean. I saw no one. I let my speed build to sixty, cut the ignition, shifted to neutral. Although Ghost Dancing had the aerodynamics of an orange crate, it coasted for more than a mile across the flats. When it came to a standstill, I put it back in gear and left it at roadside. There was no one. Listening, I walked into the scrub. The desert does its best talking at night, but on that spring evening it kept God’s whopping silence; and that too is a desert voice.

I’ve read that a naked eye can see six thousand stars in the hundred billion galaxies, but I couldn’t believe it, what with the sky white with starlight. I saw a million stars with one eye and two million with both. Galileo proved that the rotation and revolution of the earth give stars their apparent movements. But on that night his evidence wouldn’t hold. Any sensible man, lying on his back among new leaves of sage, in the warm sand that had already dried, even he could see Arcturus and Vega and Betelgeuse just above, not far at all, wheeling about the earth. Their paths cut arcs, and there was no doubt about it.

The immensity of sky and desert, their vast absences, reduced me. It was as if I were evaporating, and it was calming and cleansing to be absorbed by that vacancy. Whitman says:

O to realize space!

The plenteousness of all, that there are no bounds,

To emerge and be of the sky, of the sun and moon and flying clouds, as one with them.

On the highway a car came and went, sounding a pitiful brief

whoosh

as it ran the dark valley. When I drove back onto the road, I saw in the headlights a small desert rodent spin across the pavement as if on wheels; from the mountains, my little machine must have looked much the same. Ahead hung the Big Dipper with a million galaxies, they say, inside its cup, and on my port side, atop the western range, the evening star held a fixed position for miles until it swung slowly around in front of me and then back to port. I had followed a curve so long I couldn’t see the bend. Only Vesper showed the truth. The highway joined U.S. 6—from Cape Cod to Long Beach, the longest federal route under one number in the days before interstates—then crossed the western mountains. Below lay the mining town of Ely.