Blue Highways (5 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

A cold drizzle fell as I wound around into the slopes of the Cumberland Mountains. Clouds like smudged charcoal turned the afternoon to dusk, and the only relief from the gloom came from a fiddler on the radio who ripped out “Turkey Bone Buzzer.”

At Ida, a sign in front of a church announced the Easter sermon: “Welcome All God’s Children: Thieves, Liars, Gossips, Bigots, Adulterers, Children.” I felt welcome. Also in Ida was one of those hitching posts in the form of a crouching livery boy reaching up to take the master’s reins; but the face of this iron Negro had been painted white and his eyes Nordic blue. Ida, on the southern edge of Appalachia, a place (they said) where change comes slowly or not at all, had a church welcoming everyone and a family displaying integrated lawn decorations.

I lost the light at Bug, Kentucky, and, two miles later, at a fork in the road with three rickety taverns in the crotch, I crossed into Tennessee. Since I had left Lexington, the Kentucky counties had been dry, kept that way, I was told, by an unwritten covenant between Bible Belt fundamentalists and moonshiners. Yet, in two dry counties, half the routine police reports in newspapers listed cases of public drunkenness. A man I spoke with did not hold moonshiners responsible; rather, he believed the problem lay with bootleggers who brought in factory whiskey. Insobriety wasn’t the worst of it; people have to know where to buy bootleg, and that requires cooperation from public officials. The solution, he said, was state liquor stores that would kill bootlegging and put an end to the corruption while doing little harm to the long tradition of the moonshiners—reasonably industrious men who pursue a business older than the Federal Revenue Department. “Shine’s paid for a lot of college education in these hills,” he said, “but don’t try to tell me that about bootleg.”

Tennessee 42 mostly kept to the crests of the steep ridges, the road twisting like tendrils of a wild grapevine. Some of the curves were so sharp I had to look out the side window to steer through them. At last the mountains opened, and I came into Livingston, Tennessee, a homely town. Things were closed but for a highway grocery where I walked the fluorescent aisles more for entertainment than need. Had I come for lard, I’d have been in the right place: seven brands in five sizes, including one thirty-eight-pound drum.

I drove back to the square and pulled up for the night in front of the Overton County Courthouse. Adolescents cruised in half-mufflered heaps; a man adjusted a television in the appliance store window; a cat rubbed against my leg; windows went dark one by one. I think someone even unplugged the red blinker light after I went to bed. And that’s how I spent my evening in Livingston, Tennessee.

H

AD

it not been raining hard that morning on the Livingston square, I never would have learned of Nameless, Tennessee. Waiting for the rain to ease, I lay on my bunk and read the atlas to pass time rather than to see where I might go. In Kentucky were towns with fine names like Boreing, Bear Wallow, Decoy, Subtle, Mud Lick, Mummie, Neon; Belcher was just down the road from Mouthcard, and Minnie only ten miles from Mousie.

I looked at Tennessee. Turtletown eight miles from Ducktown. And also: Peavine, Wheel, Milky Way, Love Joy, Dull, Weakly, Fly, Spot, Miser Station, Only, McBurg, Peeled Chestnut, Clouds, Topsy, Isoline. And the best of all, Nameless. The logic! I was heading east, and Nameless lay forty-five miles west. I decided to go anyway.

The rain stopped, but things looked saturated, even bricks. In Gainesboro, a hill town with a square of businesses around the Jackson County Courthouse, I stopped for directions and breakfast. There is one almost infallible way to find honest food at just prices in blue-highway America: count the wall calendars in a cafe.

No calendar: Same as an interstate pit stop.

One calendar: Preprocessed food assembled in New Jersey.

Two calendars: Only if fish trophies present.

Three calendars: Can’t miss on the farm-boy breakfasts.

Four calendars: Try the ho-made pie too.

Five calendars: Keep it under your hat, or they’ll franchise.

One time I found a six-calendar cafe in the Ozarks, which served fried chicken, peach pie, and chocolate malts, that left me searching for another ever since. I’ve never seen a seven-calendar place. But old-time travelers—road men in a day when cars had running boards and lunchroom windows said

AIR COOLED

in blue letters with icicles dripping from the tops—those travelers have told me the golden legends of seven-calendar cafes.

To the rider of back roads, nothing shows the tone, the voice of a small town more quickly than the breakfast grill or the five-thirty tavern. Much of what the people do and believe and share is evident then. The City Cafe in Gainesboro had three calendars that I could see from the walk. Inside were no interstate refugees with full bladders and empty tanks, no wild-eyed children just released from the glassy cell of a stationwagon backseat, no longhaul truckers talking in CB numbers. There were only townspeople wearing overalls, or catalog-order suits with five-and-dime ties, or uniforms. That is, here were farmers and mill hands, bank clerks, the dry goods merchant, a policeman, and chiropractor’s receptionist. Because it was Saturday, there were also mothers and children.

I ordered my standard on-the-road breakfast: two eggs up, hashbrowns, tomato juice. The waitress, whose pale, almost translucent skin shifted hue in the gray light like a thin slice of mother of pearl, brought the food. Next to the eggs was a biscuit with a little yellow Smiley button stuck in it. She said, “You from the North?”

“I guess I am.” A Missourian gets used to Southerners thinking him a Yankee, a Northerner considering him a cracker, a Westerner sneering at his effete Easternness, and the Easterner taking him for a cowhand.

“So whata you doin’ in the mountains?”

“Talking to people. Taking some pictures. Looking mostly.”

“Lookin’ for what?”

“A three-calendar cafe that serves Smiley buttons on the biscuits.”

“You needed a smile. Tell me really.”

“I don’t know. Actually, I’m looking for some jam to put on this biscuit now that you’ve brought one.”

She came back with grape jelly. In a land of quince jelly, apple butter, apricot jam, blueberry preserves, pear conserves, and lemon marmalade, you always get grape jelly.

“Whata you lookin’ for?”

Like anyone else, I’m embarrassed to eat in front of a watcher, particularly if I’m getting interviewed. “Why don’t you have a cup of coffee?”

“Cain’t right now. You gonna tell me?”

“I don’t know how to describe it to you. Call it harmony.”

She waited for something more. “Is that it?” Someone called her to the kitchen. I had managed almost to finish by the time she came back. She sat on the edge of the booth. “I started out in life not likin’ anything, but then it grew on me. Maybe that’ll happen to you.” She watched me spread the jelly. “Saw your van.” She watched me eat the biscuit. “You sleep in there?” I told her I did. “I’d love to do that, but I’d be scared spitless.”

“I don’t mind being scared spitless. Sometimes.”

“I’d love to take off cross country. I like to look at different license plates. But I’d take a dog. You carry a dog?”

“No dogs, no cats, no budgie birds. It’s a one-man campaign to show Americans a person can travel alone without a pet.”

“Cain’t travel without a dog!”

“I like to do things the hard way.”

“Shoot! I’d take me a dog to talk to. And for protection.”

“It isn’t traveling to cross the country and talk to your pug instead of people along the way. Besides, being alone on the road makes you ready to meet someone when you stop. You get sociable traveling alone.”

She looked out toward the van again. “Time I get the nerve to take a trip, gas’ll cost five dollars a gallon.”

“Could be. My rig might go the way of the steamboat.” I remembered why I’d come to Gainesboro. “You know the way to Nameless?”

“Nameless? I’ve heard of Nameless. Better ask the amlance driver in the corner booth.” She pinned the Smiley on my jacket. “Maybe I’ll see you on the road somewhere. His name’s Bob, by the way.”

“The ambulance driver?”

“The Smiley. I always name my Smileys—otherwise they all look alike. I’d talk to him before you go.”

“The Smiley?”

“The amlance driver.”

And so I went looking for Nameless, Tennessee, with a Smiley button named Bob.

“I

DON’T

know if I got directions for where you’re goin’,” the ambulance driver said. “I

think

there’s a Nameless down the Shepardsville Road.”

“When I get to Shepardsville, will I have gone too far?”

“Ain’t no Shepardsville.”

“How will I know when I’m there?”

“Cain’t say for certain.”

“What’s Nameless look like?”

“Don’t recollect.”

“Is the road paved?”

“It’s possible.”

Those were the directions. I was looking for an unnumbered road named after a nonexistent town that would take me to a place called Nameless that nobody was sure existed.

Clumps of wild garlic lined the county highway that I hoped was the Shepardsville Road. It scrimmaged with the mountain as it tried to stay on top of the ridges; the hillsides were so steep and thick with oak, I felt as if I were following a trail through the misty treetops. Chickens, doing more work with their necks than legs, ran across the road, and, with a battering of wings, half leapt and half flew into the lower branches of oaks. A vicious pair of mixed-breed German shepherds raced along trying to eat the tires. After miles, I decided I’d missed the town—assuming there truly

was

a Nameless, Tennessee. It wouldn’t be the first time I’d qualified for the Ponce de Leon Believe Anything Award.

I stopped beside a big man loading tools in a pickup. “I may be lost.”

“Where’d you lose the right road?”

“I don’t know. Somewhere around nineteen sixty-five.”

“Highway fifty-six, you mean?”

“I came down fifty-six. I think I should’ve turned at the last junction.”

“Only thing down that road’s stumps and huckleberries, and the berries ain’t there in March. Where you tryin’ to get to?”

“Nameless. If there is such a place.”

“You might not know Thurmond Watts, but he’s got him a store down the road. That’s Nameless at his store. Still there all right, but I might not vouch you that tomorrow.” He came up to the van. “In my Army days, I wrote Nameless, Tennessee, for my place of birth on all the papers, even though I lived on this end of the ridge. All these ridges and hollers got names of their own. That’s Steam Mill Holler over yonder. Named after the steam engine in the gristmill. Miller had him just one arm but done a good business.”

“What business you in?”

“I’ve always farmed, but I work in Cookeville now in a heatin’ element factory. Bad back made me go to town to work.” He pointed to a wooden building not much bigger than his truck. By the slanting porch, a faded Double Cola sign said

J M WHEELER STORE

. “That used to be my business. That’s me—Madison Wheeler. Feller came by one day. From Detroit. He wanted to buy the sign because he carried my name too. But I didn’t sell. Want to keep my name up.” He gave a cigarette a good slow smoking. “Had a decent business for five years, but too much of it was in credit. Then them supermarkets down in Cookeville opened, and I was buyin’ higher than they was sellin’. With these hard roads now, everybody gets out of the hollers to shop or work. Don’t stay up in here anymore. This tar road under my shoes done my business in, and it’s likely to do Nameless in.”

“Do you wish it was still the old way?”

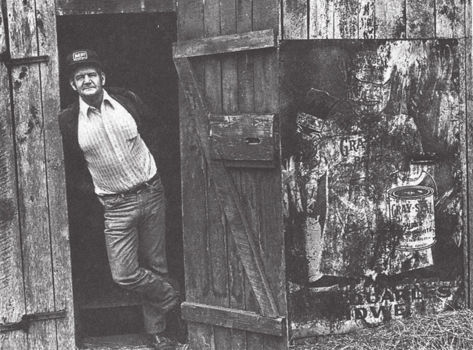

3. Madison Wheeler outside Nameless, Tennessee

“I got no debts now. I got two boys raised, and they never been in trouble. I got a brick house and some corn and tobacco and a few Hampshire hogs and Herefords. A good bull. Bull’s pumpin’ better blood than I do. Real generous man in town let me put my cow in with his stud. I couldna paid the fee on that specimen otherwise.” He took another long, meditative pull on his filtertip. “If you’re satisfied, that’s all they are to it. I’ll tell you, people from all over the nation—Florida, Mississippi—are comin’ in here to retire because it’s good country. But our young ones don’t stay on. Not much way to make a livin’ in here anymore. Take me. I been beatin’ on these stumps all my life, tryin’ to farm these hills. They don’t give much up to you. Fightin’ rocks and briars all the time. One of the first things I recollect is swingin’ a briar blade—filed out of an old saw it was. Now they come in with them crawlers and push out a pasture in a day. Still, it’s a grudgin’ land—like the gourd. Got to hard cuss gourd seed, they say, to get it up out of the ground.”

The whole time, my rig sat in the middle of the right lane while we stood talking next to it and wiped at the mist. No one else came or went. Wheeler said, “Factory work’s easier on the back, and I don’t mind it, understand, but a man becomes what he does. Got to watch that. That’s why I keep at farmin’, although the crops haven’t ever throve. It’s the doin’ that’s important.” He looked up suddenly. “My apologies. I didn’t ask what you do that gets you into these hollers.”