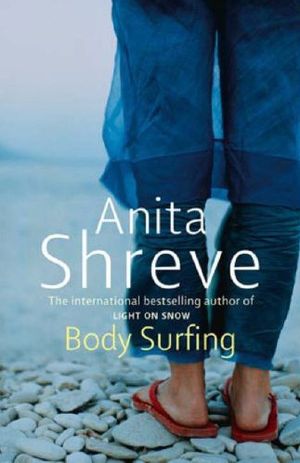

Body Surfing

Body Surfing (2007)

Anita Shreve

*

At the age of 29, Sydney has already been once divorced and once widowed. Trying to regain her footing once again, she has answered an ad to tutor the teenage daughter of a well-to-do couple as they spend a sultry summer in their oceanfront New Hampshire cottage. But when the Edwards' two grown sons, Ben and Jeff, arrive at the beach house, Sydney finds herself caught up in a destructive web of old tensions and bitter divisions. As the brothers vie for her affections, the fragile existence Sydney has rebuilt for herself is threatened.

Three o'clock, the dead hour. The faint irritation of sand grit between bare foot and floorboards. Wet towels hanging from bedposts and porch railings. A door, caught in a gust, slams, and someone near it emits the expected cry of surprise. A southwest wind, not the norm even in August, sends stifling air into the many rooms of the old summerhouse. The hope is for an east wind off the water, and periodically someone says it.

An east wind now would be a godsend.

The energy of the morning has dissipated itself in fast walks and private lessons, in vigorous reading and lazy tennis. Even in a brief expedition to a showroom in Portsmouth to look at Audi Quattros. Mrs. Edwards, Sydney has been told, will need a new car in the fall.

There are guests in the house who must be attended to. One hopes for visitors with initiative, like a refreshing east wind. They are not Sydney's concern. Her afternoons are free. Her entire life, but for a few hours each day of overpaid tutoring, is disconcertingly free.

She changes into a black tank suit, the elastic sprung in the legs. She is twenty-nine and fit enough. Her hair is no color she has ever been able to describe. She is not a blonde or a brunette, but something in between that washes out in January, comes to life in August. Gold highlights on translucence.

Sydney has been married twice: once divorced and once widowed. Others, hearing this information for the first time, find it surprising, as if this fact might be the most interesting thing about her.

On the porch, red geraniums are artfully arranged against the lime-green of the dune grass, the blue of the water. Not quite primary colors, hues seen only in nature.

Knife blades of grass pierce the wooden slats of the boardwalk. Sweet pea overtakes the thatch. Unwanted fists of thistle push upward from the sand. On the small deck at the end of the boardwalk are two white Adirondack chairs, difficult to get out of, and a faded umbrella lying behind them. Two rusted and immensely heavy iron bases for the umbrella sit in a corner, neither of which, Sydney guesses, will ever leave the deck.

Wooden steps with no railing lead to a crescent-shaped beach to the left, a rocky coastline to the right. Sydney runs across the hot sand to the edge of the water. The surf is a series of sinuous rolls, and when she closes her eyes, she can hear the spray. She prepares herself for the cold. Better than electroshock therapy, Mr. Edwards always says, for clearing the head.

A seizure of frigid water, a roiling of white bubbles. The sting of salt in the sinuses as she surfaces. She stands and stumbles and stands again and shakes herself like a dog. She hugs her hands to her chest and relaxes only when her feet begin to numb. She dives once more, and when she comes up for air she turns onto her back, letting the waves, stronger and taller than they appear from shore, carry her up and over the crest and down again into the trough. She is buoyant flotsam, shocked into sensibility.

She body surfs in the ocean, getting sand down the neckline of her suit. As a child, when she took off her bathing suit, she would find handfuls of sand in the crotch. She lowers herself into the ocean to wash away the mottled clumps against her stomach, but then she sees a good wave coming. She stands and turns her back to it and springs onto the crest. The trick always is to catch the crest. Hands pointed, eyes shut, she is a bullet through the white surge. She scrapes her naked hip and thigh against the bottom.

She crawls onto the sand, the undertow carving hollows beneath her shins. A wave she hasn't braced for hits her back and neck. She wipes the tangle of hair from her face, the water from her eyes. She sees a shape on the beach that wasn't there before. A tanned chest, a splotch of red. A man in bathing trunks is holding a pink cloth, wide and lurid, before her.

"I've been sent with a towel. You're Sydney, right?"

How extraordinary if she weren't. Not another body in the water for a thousand yards.

Inside the house, the furniture is white, a good idea in theory, not in practice. The slipcovers on the two sofas are marked with faint smudges and worried stains, navy lint from a woolen sweater. Fine grains of sand have repeatedly scratched the surface of the maple floor as if it had been lightly scoured.

On the stairs down to the basement sits a basket of old newspapers, a wicker catchall for objects that are not part of the neutral decor but might prove useful. A sparkling purple leash. A neon pink pad of Post-it Notes. A Day-Glo orange life vest. Practicality and sports rife with unnatural color.

Although Mrs. Edwards gives the impression of having inhabited the cottage for decades, perhaps even generations (already there are family rituals, oft-repeated memories, old canning jars full of sea glass used as doorstops), they have owned the house only since 1997. Before then, Mr. Edwards confided, they simply rented other cottages nearby. In contrast to his wife, he seems a man incapable of deceit.

Sydney shares a bathroom with the guests, a couple from New York who have come in search of antiques. In the mornings, there are aqua spills of toothpaste in the sink, pink spots of makeup on the mirror. Used tissues are tucked behind the spigots. Sydney routinely washes out the sink with a hand towel before she uses it. She stuffs the towel into the hamper in the hallway on her way back to her room.

It was obvious immediately to Sydney that the Edwardses' eighteen-year-old daughter, Julie, was slow, that no amount of tutoring would adequately prepare her for the stellar senior year of high school Mrs. Edwards hopes for, a year that is almost certain, in Sydney's opinion, to defeat the girl. Mrs. Edwards speaks knowledgeably of Mount Holyoke and Swarthmore. Skidmore as a safety. Sydney can only blink with wonder. Julie is pliant, eager to please, and extraordinarily beautiful, her skin clear and pink, her eyes a sea-glass blue. Sydney can see that the girl, who seems willing to study all the hours of the day, will disappoint her mother and break her father's heart, the latter not because she won't get into the colleges Mrs. Edwards seems so knowledgeable about, but because she will try so hard and fail.

Salt encrusts the windows of the house on the diagonal, as if water had been thrown against the glass. The windows out to the porch have to be washed twice a week to provide any appreciation of the view, which is spectacular.

Sydney sometimes senses that her presence has upset the family equilibrium. She tries to be available when needed, present but silent when not.

The brothers will sleep in a room called the "boys' dorm." Julie has a room on the ocean side of the house. Mr. and Mrs. Edwards's bedroom looks out over the marshes. The guests, like Sydney, have been relegated to a room with twin beds.

Mr. and Mrs. Edwards have invited Sydney to call them by their first names. When she tries to say Anna or Mark, however, the words stick in her throat. She finds other ways to refer to the couple, such as your husband and he and your dad.

Sydney's first husband was an air racer. He flew through trees at 250 miles an hour and performed aerobatic stunts over a one-mile course. If he were to graze a gate or become momentarily disoriented by the Gs, he would hurtle to the ground and crash. When she could, Sydney went with Andrew to these races--to Scotland and Vienna and San Francisco--and watched him twist his plane in the air at 420 degrees per second. At air shows, Andrew was a star and signed autographs. He wore fireproof clothing and a crash helmet and was equipped with a parachute--not that a parachute would have been at all helpful thirty feet off the ground. For a year, Sydney found the air races exotic and thrilling. During the second year, she began to be afraid. Contemplating a third year and the possibility of a child, she pictured Andrew's fiery death and said, Enough. Her aviator, who seemed genuinely sad to see the marriage end, could not, however, be expected to give up flying.

Sydney met her second husband when she was twenty-six. Her right front tire blew on the Massachusetts Turnpike, and she pulled to the side of the road. A minute later, her Honda Civic was hit from behind. Because she had been standing at the front of the car and looking down at the tire, she was hit and briefly dragged along the pavement. Daniel Feldman, who had to cut the clothes off her body in the emergency room of Newton-Wellesley Hospital, chided her for pulling to a stop on a bridge. A week later, he took her to Biba in Boston.

Eight months into their marriage, and during his residency at Beth Israel, Daniel suffered a burst aneurysm in his brain. Receiving the news by telephone, Sydney was stunned, bewildered, wide-eyed with shock.

Most people, mindful of the sensitivities, do not point out to Sydney the irony of having divorced a man she was afraid would die only to marry a man who perished in the very place he ought to have been saved. But she can tell that Mr. Edwards is eager to discuss the situation. Despite his kindness and his affability, he cannot help but flirt with the details.

"Is the aviator still flying?" he asks one night as they are washing dishes. "Did you say your husband interned at the B.I.?"

Mrs. Edwards, by contrast, is not afraid of the blunt question.

"Are you Jewish?" she asked as she was showing Sydney to her room.

It wasn't clear to Sydney which answer Mrs. Edwards would have preferred: Jewish being more interesting; not Jewish being more acceptable.

The doctor was Jewish. The aviator was not.

Sydney is both, having a Jewish father and his cheekbones but a Unitarian mother, from whom she has inherited her blue eyes. Even Sydney's hair seems equal parts father and mother--the wayward curl, the nearly colorless blond. Sydney became Bat Mitzvah before her parents separated but then was strenuously raised to be a WASP during her teenage years. She thinks of both phases of her life as episodes of childhood having little to do with the world as she now encounters it, neither religion at all helpful during the divorce and death.

Not unlike a parachute at thirty feet.

For a week last summer, Sydney went to stay with Daniel's parents in Truro. The experiment was a noble one. Mrs. Feldman, whom she had briefly called Mom, had had the idea that Sydney's presence would be comforting. In fact the opposite was true, the sight of Sydney sending Mrs. Feldman into contagious fits of weeping.

For days following Daniel's death, Sydney's own mother refused to believe in the simple fact of the event, causing Sydney to have to say, over and over again, that Daniel had died of a brain aneurysm.

"But how?" her mother repeatedly asked.

Sydney's father came up from New York by train for the funeral. He wore a taupe trench coat, put on a yarmulke for the service, and, astonishingly, he wept. Afterwards, at dinner, he tried to reassure her.

"I think of you as resilient," he said over steak and baked potato.

The double blow of the divorce and death left Sydney in a state of emotional paralysis, during which she was unable to finish her thesis in developmental psychology and had to withdraw from her graduate program at Brandeis. Since then, she has taken odd jobs created by friends and family, jobs for which she has been almost ludicrously overqualified or completely out of her depth: a secretary in the microbiology department at Harvard Medical School (overqualified); a dealer's assistant at an art gallery on Newbury Street (out of her depth). She has been grateful for these jobs, for the opportunity to drift and heal, but recently she has begun to wonder if this strange and unproductive period of her life might be coming to an end.

"You must be the tutor."

"And you are?"

"Ben. That's Jeff on the porch."

"Thank you for the towel."

"You're quite the body surfer."

Sydney discovers that she minds the loss of her mourning. When she grieved, she felt herself to be intimately connected to Daniel. But with each passing day, he floats away from her. When she thinks about him now, it is more as a lost possibility than as a man. She has forgotten his breath, his musculature.