Bold They Rise: The Space Shuttle Early Years, 1972-1986 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History of S) (51 page)

Authors: David Hitt,Heather R. Smith

Tags: #History

32.

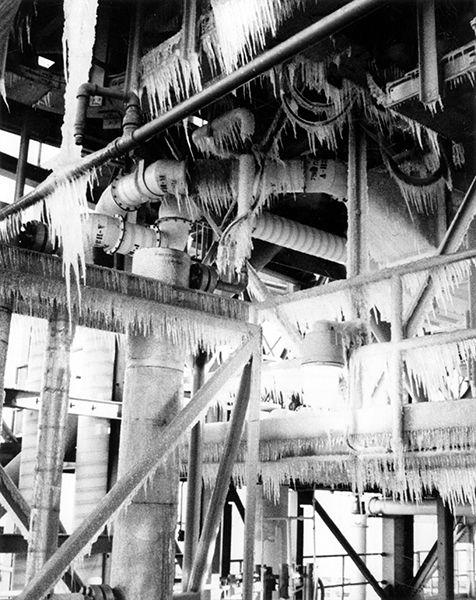

On the day of Space Shuttle

Challenger

’s 28 January 1986 launch, icicles draped the launch complex at the Kennedy Space Center. Courtesy

NASA

.

The second potential implication was more complicated. No shuttle had ever launched in temperatures below fifty degrees Fahrenheit before, and there were concerns about how the subfreezing temperatures would affect the vehicle, and in particular, the O-rings in the solid rocket boosters. The boosters each consisted of four solid-fuel segments in addition to the nose cone with the parachute recovery system and the motor nozzle. The segments were assembled with rubberlike O-rings sealing the joints between the segments. Each joint contained both a primary and a secondary O-ring for additional safety. Engineers were concerned that the cold temperatures would cause the O-rings to harden such that they would not fully seal the joints, allowing the hot gasses in the motor to erode them. Burn-through erosion had occurred on previous shuttle flights, and while it had never caused significant problems, engineers believed that there was potential for serious consequences.

During a teleconference held the afternoon before launch,

SRB

contractor Morton Thiokol expressed concerns to officials at Marshall Space Flight Center and Kennedy Space Center about the situation. During a second teleconference later that evening, Marshall Space Flight Center officials challenged a Thiokol recommendation that

NASA

not launch a shuttle at temperatures below fifty-three degrees Fahrenheit. After a half-hour off-line discussion, Thiokol reversed its recommendation and supported launch the next day. The three-hour teleconference ended after 11:00 p.m. (in Florida’s eastern time zone).

During discussions the next morning, after the crew was already aboard the vehicle, orbiter contractor Rockwell International expressed concern that the ice on the orbiter could come off during engine ignition and ricochet and damage the vehicle. The objection was speculation, since no launch had taken place in those conditions, and the

NASA

Mission Management Team voted to proceed with the launch. The accident investigation board later reported that the Mission Management Team members were informed of the concerns in such a way that they did not fully understand the recommendation.

Launch took place at 11:38 a.m. on 28 January. The three main engines ignited seconds earlier, at 11:37:53, and the solid rocket motors ignited at 11:38:00. In video of the launch, smoke can be seen coming from one of the aft joints of the starboard solid rocket booster at ignition. The primary O-ring failed to seal properly, and hot gasses burned through both the primary and secondary O-rings shortly after ignition. However, residue from burned propellant temporarily sealed the joint. Three seconds later, there was no longer smoke visible near the joint.

Launch continued normally for the next half minute, but at thirty-seven seconds after solid rocket motor ignition, the orbiter passed through an area of high wind shear, the strongest series of wind shear events recorded thus far in the shuttle program. The worst of the wind shear was encountered at fifty-eight seconds into the launch, right as the vehicle was nearing “Max Q,” the period of the highest launch pressures, when the combination of velocity and air resistance is at its maximum. Within a second, video captured a plume of flame coming from the starboard solid rocket booster in the joint where the smoke had been seen. It is believed that the wind shear broke the temporary seal, allowing the flame to escape. The plume rapid

ly became more intense, and internal pressure in the motor began dropping. The flame occurred in a location such that it quickly reached the external fuel tank.

The gas escaping from the solid rocket booster was at a temperature around six thousand degrees Fahrenheit, and it began burning through the exterior of the external tank and the strut attaching the solid rocket booster to the tank. At sixty-four seconds into the launch, the flame grew stronger, indicating that it had caused a leak in the external tank and was now burning liquid hydrogen escaping from the aft tank of the external tank. Approximately two seconds later, telemetry indicated decreasing pressure from the tank.

At this time, in the vehicle and in Mission Control, the launch still appeared to be proceeding normally. Having made it through Max Q, the vehicle throttled its engines back up. At sixty-eight seconds, Covey informed the crew it was “Go at throttle up.” Commander Dick Scobee responded, “Roger, go at throttle up,” the last communication from the vehicle.

Two seconds later, the flame had burned through the attachment strut connecting the starboard

SRB

and the external tank. The upper end of the booster was swinging on its strut and impacted with the external tank, rupturing the liquid oxygen tank at the top of the external tank. An orange fireball appeared as the oxygen began leaking. At seventy-three seconds into the launch, the crew cabin recorder records Pilot Michael Smith on the intercom saying, “Uh-oh,” the last voice recording from

Challenger

.

While the fireball caused many to believe that the Space Shuttle had exploded, such was not the case. The rupture caused the external tank to lose structural integrity, and at the high velocity and pressure it was experiencing, it quickly began disintegrating. The two solid rocket boosters, still firing, disconnected from the shuttle stack and flew freely for another thirty-seven seconds. The orbiter, also now disconnected and knocked out of proper orientation by the disintegration of the external tank, began to be torn apart by the aerodynamic pressures. The orbiter rapidly broke apart over the ocean, with the crew cabin, one of the most solid parts of the vehicle, remaining largely intact until it made contact with the water.

All of that would eventually be revealed during the course of the accident investigation. At Mission Control, by the time the doors were opened again, much was still unknown, according to Covey.

[We] had no idea what had happened, other than this big explosion. We didn’t know if it was an

SRB

that exploded. I mean, that was what we thought. We always thought

SRB

s would explode like that, not a big fireball from the external tank propellants coming together. So then that set off a period then of just trying to deal with that and the fact that we had a whole bunch of spouses and families that had lost loved ones and trying to figure out how to deal with that.

The families were in Florida, and I remember, of course, the first thing I wanted to do was go spend a little time with my family, and we did that. But then we knew the families were coming back from Florida and out to Ellington [Field, Houston], so a lot of us went out there to just be there when they came back in. I remember it was raining. Generally they were keeping them isolated, but a big crowd of us waiting for them, they loaded them up to come home. Then over the next several days most of the time we spent was trying to help the Onizukas in some way; being around. Helping them with their family as the families flew in and stuff like that.

After being in Mission Control for approximately twelve hours—half of that prior to launch and the rest in lockdown afterward, analyzing data, Gregory finally headed home.

The families had all been down at the Kennedy Space Center for the liftoff, and they were coming back home. Dick Scobee, who was the commander, lived within a door or two of me. And when I got home, I actually preceded the families getting home; I remember that. They had the television remote facilities already set up outside of the Scobees’ house, and it was disturbing to me, and so I went over and, in fact, invited some of those [reporters] over to my house, and I just talked about absolutely nothing to get them away from the house, so that when June Scobee and the kids got back to the house, they wouldn’t have to go through this gauntlet.

The next few days, Gregory said, were spent protecting the crew’s families from prying eyes. “There was such a mess over there that Barbara and I took [Scobee’s] parents and just moved them into our house, and they must have stayed there for about four or five days. Then June Scobee, in fact, came over and stayed, and during that time is when she developed this concept for the Challenger Center. She always gives me credit for being the one who encouraged her to pursue it, but that’s not true. She was going to do it, and it was the right thing to do.”

Gregory recalled spending time with the Scobees and the Onizukas and the Smiths, particularly Mike Smith’s children. “It was a tough time,” he said.

It was a horrible time, because I had spent a lot of time with Christa McAuliffe and [her backup] Barbara Morgan, and the reason was because I had teachers in my family. On my father’s side, about four or five generations; on my mother’s side, a couple of generations. My mother was elementary school, and my dad was more in the high school. But Christa and I and Barbara talked about how important it was, what she was doing, and then what she was going to do on orbit and how it would be translated down to the kids, but then what she was going to do once she returned. So it was traumatic for me, because not only had I lost these longtime friends, with Judy Resnik and Onizuka and Ron McNair and Scobee, and then Mike Smith, who was a class behind us, but I had lost this link to education when we lost Christa.

Astronaut Sally Ride was on a commercial airliner, flying back to Houston, when the launch tragedy occurred. “It was the first launch that I hadn’t seen, either from inside the shuttle or from the Cape or live on television,” Ride recalled.

The pilot of the airline, who did not know that I was on the flight, made an announcement to the passengers, saying that there had been an accident on the

Challenger

. At the time, nobody knew whether the crew was okay; nobody knew what had happened. Thinking back on it, it’s unbelievable that the pilot made the announcement he made. It shows how profoundly the accident struck people. As soon as I heard, I pulled out my

NASA

badge and went up into the cockpit. They let me put on an extra pair of headsets to monitor the radio traffic to find out what had happened. We were only about a half hour outside of Houston; when we landed, I headed straight back to the Astronaut Office at

JSC

.

Payload Specialist Charlie Walker was returning home from a trip to San Diego, California, when the accident occurred.

I can remember having my bags packed and having the television on and searching for the station that was carrying the launch. As I remember it, all the stations had the launch on; it was the Teacher in Space mission. So I watched the launch, and to this day, and even back then I was still aggravated with news services that would cover a launch up until about thirty seconds, forty-five sec

onds, maybe one minute in flight, after Max Q, and then most of them would just cut the coverage. “Well, the launch has been successful.” [I would think,] “You don’t know what you’re talking about. You’re only thirty seconds into this thing, and the roughest part is yet to happen.”

And whatever network I was watching ended their coverage. “Well, looks like we’ve had a successful launch of the first teacher in space.” And they go off to the programming, and it wasn’t but what, ten seconds later, and I’m about to pick my bags up and just about to turn off the television and go out my room door when I hear, “We interrupt this program again to bring you this announcement. It looks like something has happened.” I can remember seeing the long-range tracker cameras following debris falling into the ocean, and I can remember going to my knees at that point and saying some prayers for the crew. Because I can remember the news reporter saying, “Well, we don’t know what has happened at this point.” I thought, “Well, you don’t know what has happened in detail, but anybody that knows anything about it can tell that it was not at all good.”

Mike Mullane was undergoing payload training with the rest of the 62

A

crew at Los Alamos Labs in New Mexico. “We were in a facility that didn’t have easy access to a

TV

,” said Mullane.

We knew they were launching, and we wanted to watch it, and somebody finally got a television or we finally got to a room and they were able to finagle a way to get the television to work, and we watched the launch, and they dropped it away within probably thirty seconds of the launch, and we then started to turn back to our training. Somebody said, “Well, let’s see if they’re covering it further on one of the other channels,” and started flipping channels, and then flipped it to a channel and there was the explosion, and we knew right then that the crew was lost and that something terrible had happened.

Mullane theorized that someone must have inadvertently activated the vehicle destruction system or a malfunction caused the flight termination system to go off. “I was certain of it,” Mullane said.

I mean, the rocket was flying perfectly, and then it just blew up. It just looked like it had been blown up from this dynamite. Shows how poor you can be as a witness to something like this, because that had absolutely nothing to do with it.