Bomb Girls--Britain's Secret Army (25 page)

Read Bomb Girls--Britain's Secret Army Online

Authors: Jacky Hyams

As dangerous as it was to manufacture the bombs or mix the explosives, it was equally hazardous to move the raw ingredients and components of the bombs around the site.

Most of the content of a shell or bomb is a high explosive chemical. In itself, the chemical is unlikely to explode without the presence of another chemical – the detonator. The detonator must be powerful and capable of exploding easily if it is given a blow or shock of some kind.

As a consequence, working with detonators and carrying them around the site was potentially lethal. Workers were not, under any circumstances, permitted to carry detonators through doorways –in case the door swung back and hit the load. So the detonators had to be lifted through hatchways in the side of the buildings.

Taking the detonators to be tested meant an employee with a red flag would walk 30 yards in front of the two people carrying the detonators. Workmen on the road who saw this thought it was a huge joke. What they didn’t know was that the detonators were capable of blowing everyone and everything sky high.

Sorting the chemicals before they were used created another big safety issue.

For instance, fulminate of mercury is safe if it is kept damp. Yet to use it in the production of shells and bombs, it needs to be dry. So the chemical had to be dried on tables, in special buildings called ‘drying houses’. It was carried around the site in small paper cups.

Another main chemical, lead azide, was more dangerous when it was wet than when it was dry. So moving this chemical around on a wet day was extremely hazardous.

ROF Aycliffe ceased to operate as a munitions site in August 1945. After the war the site was converted into an industrial estate renamed Newton Aycliffe and the area itself became a new town in 1947.

As hard, dangerous and draining as the work was, after the war the women who had worked there remembered their lighter moments the lunchtime concerts, the canteen lunches and, most importantly, the friendships and close bonds they formed at the factory. Many went on to last a lifetime.

Today, Newton Aycliffe is the second largest industrial estate in the north east. Some of the blast walls and buildings that housed the workers can still be seen, proud testament to the work of the courageous Aycliffe Angels.

DRUNGANS, DUMFRIES, SCOTLAND

(MARGARET PROUDLOCK’S STORY)

The Drungans site at Cargenbridge, Dumfries, is the largest industrial complex in the Dumfries and Galloway region.

In 1939, it was selected by ICI and the Government as a suitable location for the manufacture of acids and nitrocellulose for explosives.

Land that had previously been used for farming was to be transformed into a top secret industrial site. The area was relatively safe from bombing, yet within reach of ICI’s factory and laboratory at Ardeer in Ayrshire.

The factory went into production in January 1941, a considerable achievement since all the construction work had to be carried out in daylight (the blackout regulations meant that lights could not be used on the building at night).

Apart from the construction of more than 40 buildings for production, storage, offices, fire station and canteen, a mile of roads and 1,900 yards of railway line were also laid.

Workers at the site came from as far away as Dundee (150 miles away). Many were billeted with local people in the area. At peak production, the site had a workforce of 1,350: more than half of the workers were women.

Through the war, more than 1.1 million tons of acid were produced at the Drungans factory. 37,500 tons of guncotton were delivered to nearby factories at Powfoot and Dalbeattie to be turned into cordite.

The factory closed down briefly in 1945 but it was reopened by ICI the following year to produce sulphuric acid for industry.

It was eventually rebuilt as a purpose built factory, initially manufacturing synthetic fibres, then it continued as a manufacturing plant for a wide range of industrial materials ranging from high quality film to packaging material. In 1998 ICI’s 60 year link to Drungans ended when the site was taken over by the international DuPont Teijin corporation.

LEVER BROTHERS/PORT SUNLIGHT, THE WIRRAL, LIVERPOOL.

(IVY GARDINER’S STORY)

The vast Port Sunlight factory and housing village in the Wirral Peninsula was created in 1887 by the Lever Brothers, William Hesketh Lever and James Darcy Lever as a model village. At first, the company made branded soap and detergent products, then it expanded into the manufacture of margarine and ice cream products until the Twenties

when it merged with a Dutch company to form Unilever, the first ever modern multinational.

The major feature of the company, right from the start, was that the Port Sunlight village adjoining the factory was built to accommodate the staff in good quality housing with extensive community and leisure facilities.

Employees and employers alike were regarded as one large family, with a workforce growing up together in a tradition of ‘enlightened industrial outlook.’

As a consequence of this, working at Port Sunlight was regarded as a bright option around the Liverpool area, when Ivy Gardiner first joined the company as a 15-year-old filling soap packets.

In August 1940, direct war work started at Port Sunlight with the manufacture of small parts and the reconditioning of blitzed machine tools from firms in the area.

Though not a purpose built munitions complex, Port Sunlight was a bombing target because of its proximity to the port of Liverpool, so strategically important for Britain.

In October 1940, the Sunlight village was severely damaged during an air raid where three people were killed. Soap production was severely reduced with the introduction of soap rationing in 1942, releasing more space and manpower for war work. By then, US Army Jeeps and giant Dodge trucks were arriving by sea in parts, in huge cases, ready to be assembled at Port Sunlight and eventually used in the North Africa campaign.

Port Sunlight’s biggest wartime engineering undertaking, The Dowty Department, was also set up in 1942 to manufacture retractable under carriages, designed by George Dowty, for Lancaster Bombers. Working on the assembly of

these under- carriages was the war work Ivy Gardiner trained for at age 21. In February 1943, the first of these under carriages left the factory to be assembled with the Lancaster bombers, ready for combat.

After the war, the factory resumed normal production. All soap production there ceased in 2001 but today, the model village at Port Sunlight is a heritage area and museum. The adjoining Unilever factory is scheduled to be extended to a high-tech factory site for personal care products like deodorant and shampoo.

ROF BLACKPOLE, WORCESTER

(MAISIE JAGGER’S STORY)

Located a mile to the north of Worcester Shrub Hill Station on the Worcester to Birmingham railway line, the Blackpole site was originally a Government owned munitions factory during the First World War. It was known as Cartridge Factory No. 3 and run by Kings Norton Metal.

In 1921, the site was purchased by Cadbury Brothers, Bournville as additional factory space until 1940 when it was requisitioned by the Government as a small arms ammunition factory producing cartridge cases.

During wartime the site had its own railway station, Blackpole Halt, to transport workers to and from the factory. The site was handed back to Cadburys in 1946.

For many years, Cadburys Cakes were produced at Blackpole until Cadbury’s merger with Schweppes in the Seventies when the site was sold. It is now a retail park.

BISHOPTON, RENFREWSHIRE

(MARGARET CURTIS’ STORY)

Bishopton was chosen as a munitions site for the manufacture of explosives because of its favourable microclimate. It was also in Clydeside, an area of high unemployment in the Thirties, and had good rail links.

Part of the site was constructed on requisitioned farm land; the southern end of the site had originally been a filling factory during World War 1, employing over 10,000 workers.

Three self-contained explosive manufacturing factories were built on the Bishopton 2,000 acre site. Construction started in 1937 and the facility, built specifically to manufacture propellant, mainly cordite, for the Army and RAF, opened at the end of 1940. The site had its own bus service and internal railway lines used to transport explosives around the site. At its peak, Bishopton employed 20,000 workers, most of them female.

Each building on the site was numbered, with Factory 0 housing the supporting services for the site. (These included a permanently manned fire station with its own fire brigade, ambulance station, medical centre, mortuary, laboratories, clothing and general stores, machine shops, general workshops and laundry).

The three main factory buildings (1, 2 and 3) each had their own coal fired power stations. Factories 1 and 2 had their own nitration plant for making nitrocellulose (known as gun cotton) which was then processed on site to produce cordite. Each factory at Bishopton had its own nitroglycerine section.

Factory 3 closed down almost immediately after WW2. The manufacture of explosives including cordite, gunpowder

and other explosives continued at Bishopton in Factories 1 and 2 until the year 2000. The site is now owned by BAE Systems.

Ordnance Survey maps did not show the existence of Bishopton until after the year 2000.

Long after WW2, it remained, as did so many other wartime munitions sites, top secret.

1940: King George VI examines a tracer shell at a Midlands ammunition factory as his wife, Queen Elizabeth, chats with a worker.

© Getty Images

The Royal visits to the arms factories were a huge morale booster for the workers.

© Getty Images

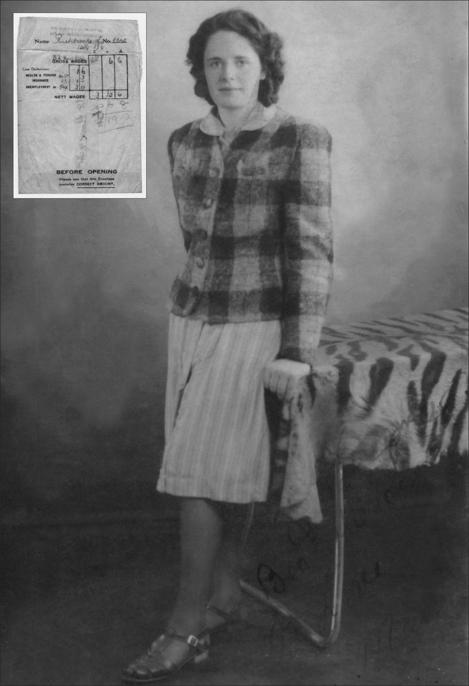

Maisie Jagger: she missed her family so much that she was transferred back to Dagenham, Essex, after making gun cartridge cases in Worcester for 18 months.

Inset: Maisie’s paypacket, March, 1942: £3.12s.6d for a week’s work making parachutes.

Ivy Gardiner’s wedding day, May 1945. Like thousands of other couples, Ivy and Wilf tied the knot just after VE Day.