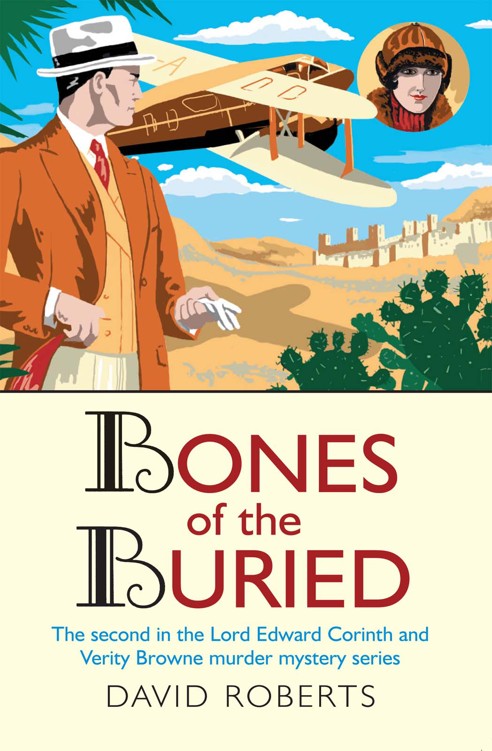

Bones of the Buried

Read Bones of the Buried Online

Authors: David Roberts

D

AVID

R

OBERTS

worked in publishing for over thirty years, most recently as a publishing director,

before devoting his energies to writing full time. He is married and divides his time between London and Wiltshire.

Praise for David Roberts

Sweet Poison

‘A classic murder mystery with as complex a plot as one could hope for and a most engaging pair of amateur sleuths whom I look forward to encountering again in future

novels.’

Charles Osbourne, author of

The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie

Bones of the Buried

‘Roberts’ use of period detail ... gives the tale terrific texture. Recommend this one heartily.’

Booklist

Hollow Crown

‘The plots are exciting and the central characters are engaging, they offer a fresh, a more accurate and a more telling picture of those less than placid

times.’

Sherlock

Dangerous Sea

‘

Dangerous Sea

is taken from more elegant times than ours, when women retained their mystery and even murder held a certain charm. The plot is both intricate and

enthralling, like Poirot on the high seas, and lovingly recorded by an author with a meticulous eye and a huge sense of fun.’

Michael Dobbs, author of

Winston’s War

and

Never Surrender

Also by David Roberts

Sweet Poison

Hollow Crown

Dangerous Sea

The More Deceived

A Grave Man

Constable & Robinson Ltd

3 The Lanchesters

162 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 9ER

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Constable,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2001

This paperback edition published by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable and Robinson Ltd, 2002

Copyright © David Roberts, 2001

The right of David Roberts to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any

form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-84119-587-2 (pbk)

ISBN 978-1-84119-385-4 (hbk)

eISBN 978-1-78033-420-2

Printed and bound in the EU

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

For Olivia

Don Adriano de Armado: The sweet war-man is dead and rotten; sweet chucks, beat not the bones of the buried; when he breathed, he was a man. William Shakespeare |

‘Boy!’ The call echoed round the house and a scurry of small black-garbed figures raced to answer it, slithering to a halt outside the library. Eight senior boys in

the house constituted ‘the library’ and it was also the name given to the room they used as a common-room. It had almost no books in it – just a broken-backed sofa, several

armchairs, all of which had seen better days, and a table with one leg amputated at the knee, supported uncertainly by a pile of textbooks. There was also a dartboard, a wind-up gramophone with a

spectacular horn, a few records in brown paper sleeves and an ancient kettle. Next to the grate, beside a couple of toasting forks, a bunch of canes rested negligently against the wall, assuming an

air of innocence which belied the very real threat that lay behind their willowy form.

The last in line was, as always, Featherstone, a small boy dressed in bum-freezers. This was the uniform reserved for first-year Etonians below a certain height. The short coat, cut off just

above the posterior, contrasted with the tail coats worn by all the other boys and marked him out as the lowest form of school life. Oliver Featherstone was very miserable. He badly missed his

father who, out of love, had inflicted upon him this particular torture. His father was the owner of several oil wells in Persia but, to Oliver’s great grief, was also the proprietor of a

famous department store on Oxford Street in London. His mother, whom he rarely saw, was a film actress whose photograph appeared in picture-papers on both sides of the Atlantic.

Unfortunately, he had discovered that neither his father’s wealth nor his mother’s celebrity was anything to be proud of at Eton. What was worse, his father’s name was not

really Featherstone but Federstein. There were several Jews at Eton, one of whom was a member of Pop, the select society of popular boys which ran the school, but the Jews whom Eton welcomed, as

Oliver painfully discovered, were the sons of merchant bankers who had bankrolled the government and the monarchy for almost a century. None of these held out to him the hand of friendship. Despite

his wealth, his father had himself been ostracised from polite society and, in a clumsy attempt to ease his son’s passage through the school and protect him from bullying, had tried to

conceal his origins by changing the spelling of his surname. It took only three weeks for it to become known that Featherstone was really Federstein and that his father was ‘a grocer’.

Oliver at once became the innocent victim of his father’s subterfuge.

‘Federstein!’ All the other small boys ran away chirruping gratefully like a swoop of starlings.

‘Yes, Hoden?’ said Oliver, wearily.

Hoden scribbled on a piece of paper, folded it several times and thrust it at him. ‘Take this to Stephen Thayer at Chandler’s, and hurry.’

‘But Hoden, please! I’ve got an essay for tomorrow and I’ve already had three rips. My tutor said it would be PS next time.’

‘Well, you’d better run then,’ said Hoden unsympathetically. When a boy’s work was not up to scratch the master – or beak as he was called at Eton – would

tear it at the top and the errant pupil would have to take it to show his housemaster. Too many rips would result in Penal Servitude – PS for short – which involved sacrificing already

scarce free time on ‘extra work’.

Highly disgruntled, Oliver set off at a run down Judy’s Passage, the narrow pedestrian way which threaded the redbrick buildings, the last of which was Stephen Thayer’s house.

Half-way, he got a stitch in his side and slowed to a walk. There was a large stone, big enough for a small boy to sit on, where the path made a dog-leg and there, strictly against the rules,

Oliver perched and unfolded the note Hoden had given him. It read: ‘Stevie, can you meet me underneath the arches tomorrow after six. Send word by the oily Jewboy, love, M. PS But he is

rather pretty isn’t he?’

Oliver’s eyes began to water. How dare this horrible man call him an oily Jewboy, and pretty. Neither his father nor his mother had told him anything about sex before he went to school.

Had he but known it, his mother was an expert on the subject but, in his eyes, she was as pure as a garden rose and it would have embarrassed him horribly if she had said anything with a view to

preparing him for life in an English public school. As for his father, he assumed that in some magical way his son was to be transformed into an English gentleman, in his view a creature second

only to the gods themselves. He visualised Eton as holy water in which his son would be purified. It was odd that a man so generally shrewd in the affairs of the world should be so naive when it

came to baptism.

Oliver looked at his hand with horror. In his anguish, and without being aware of what he was doing, he had scrumpled up Hoden’s note. He couldn’t deliver it now without Thayer

knowing that he had opened it but he dared not go back without an answer. The tears began to trickle down his cheeks. Half-blinded by the savage grief of childhood, he did not notice that someone

was walking down the passage towards him. It was the very boy to whom he was to deliver the note.

‘What’s up, Featherstone – that is your name, isn’t it? Come now, why are you blubbing?’

He spoke not unkindly and Oliver was persuaded to hold up the crumpled piece of paper for his inspection. ‘I’m . . . I’m truly sorry, Thayer. I didn’t mean to open it. It

just sort of came undone.’

Thayer took the note, read it and blushed deeply. He bit his lip and tried to decide what to say. He knew he could get into bad trouble if the substance of the message came to the attention of

his housemaster, and Hoden would certainly be sacked. Homosexual feelings, though common enough in a single sex school, or indeed because they were so common, were anathema to the authorities and

no housemaster would hesitate to have a boy removed from the school if anything of the kind was proved against him.

Damn Hoden, Thayer thought. He really would have to drop him. ‘Stop all that noise, Featherstone. No one’s going to punish you but really, you know, it was very wrong of you to open

a private note.’

‘Ye . . . s,’ Oliver agreed. ‘Should I say anything to Hoden? He may want to whack me.’

‘No,’ said Thayer hurriedly. ‘Don’t do that. I got the message and no one else saw it. We’ll leave it at that. No harm done.’

‘No . . .? Thank you, sir.’

‘Don’t call me “sir”, you little idiot. You only call beaks “sir”.’

‘Yes, Thayer.’

‘Oh, and don’t get upset about people calling you . . . names. You can’t help being . . . whatever it is he said you were . . . not oily I mean but the other. It’s

nothing to be ashamed of. Now off you go, and remember: say nothing of this to anyone or you will get into trouble.’

‘Yes, Thayer. And thank you,’ said the small boy, managing a smile. Could it be that this god figure, a member of Pop and therefore one of Eton’s elect, was going to forgive

him, to be compassionate? It never occurred to him for a moment that he, the most miserable of worms, had through an accident, through his own clumsiness, gained a measure of power over one so

mighty. He looked at Thayer, noticing him for the first time as a person – his expensively cut hair, his coloured waistcoat, which only members of Pop could wear, gleaming like armour, his

buttonhole freshly cut that morning in his tutor’s garden. From his white ‘stick-up’ collar to his shoes shiny enough to reflect his face, Thayer was perfect and Oliver felt an

overwhelming desire to fall on his knees and worship.