Bonzo's War (48 page)

Authors: Clare Campbell

British Library (Newspapers)

NARPAC carried on â while behind the scenes its constituent charities rowed incessantly. The Government despaired. Meanwhile not many of the public seemed to know the strange organization existed, but where they did, they were enthusiastic supporters. Above, pet-loving ladies queue to have their cats and dogs registered at an Animal Guard Post near the British Museum.

It was food, not bombs, however that would really dictate the fate of wartime pets. There was no food ration for companion animals and from mid-1940 it was a punishable offence to give them anything judged fit for human consumption. Manufactured pet-food like Chappie (

above

) made of horsemeat was restricted before disappearing completely.

Imperial War Museum

It was not just ladies who hurled themselves into wartime pet rescue. London Transport bus-driver Mr. Arthur Heelas found feline fame in 1940â1 as the âfairy godfather' of the capital's bombed-out cats.

Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museum

Impenal War Museum

Impenal War Museum

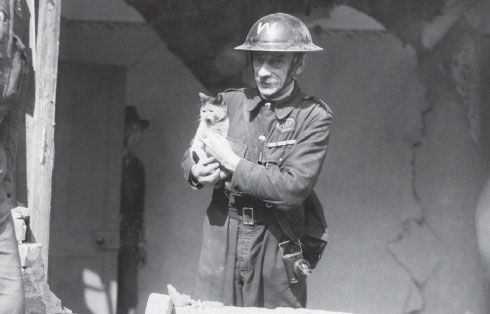

Cats under fire showed an amazing ability to survive unscathed in bombed buildings, inspiring rejoicing when they were discovered, sometimes days later, in some impossible crevice

(opposite and top)

. This lucky dog meanwhile survived to make it to the Our Dumb Friends' League (Blue Cross) hospital in Victoria â where, in December 1940, a jolly Christmas party was held for bombed-out dogs.

Getty Images

Pets were never far from war at the top. Hitler's entourage was dogs-only. He was said to regard his mistress Eva Braun's Scotties âStasi' and âNegus' as âludicrous,' although he seems fond enough of them in this Alpine encounter at the âEagle's Nest'. According to reports, Negus was killed in April 1945 by a grenade and Stasi was last seen alive by neighbours of the Brauns in Munich, âwandering the streets like many other post-war strays.'

Winston Churchill in contrast was surrounded by cats throughout. Opposite

(top)

, the wartime Prime Minister makes a pet of âBlackie' aboard HMS

Prince of Wales

in mid 1941. Poor Blackie would survive the sinking of the battleship by Japanese bombers and get to shore only to be lost in the Malayan jungle. No such fate awaited âMary' the goat kept by Deputy Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, in his suburban north London garden along with chickens and rabbits â one of an army of wartime urban smallholders

(right)

.

Imperial War Museum

Getty Images

The National Archives

The Times archive

With no meat ration for hungry dogs, many families responded to the call to offer their pets to the military, with tearful farewells at railway stations as they were sent off for assessment and training. Would they ever come home?

Alsatians (German Shepherds) were favoured by the RAF for airfield guard duties

(opposite top)

while the Army used various breeds for mine hunting. âDogs with black eyes are surly and erratic, dogs with light eyes are generally wilful,' it was noted. âHazel-eyed dogs' were ideal. Here

(opposite middle)

a Royal Engineer mine-dog section goes into action in Normandy soon after D-Day. Casualties were high and death in action was formally notified to grieving families by the War Office

(opposite bottom)

.