Book of Fire (41 page)

Anne was known as a protector of Tyndale’s readers. An evangelical named Thomas Alwaye petitioned her after he was prosecuted for buying a Tyndale Testament. ‘I remembered how many deeds of pity your goodness had done within these few years,’ he wrote, ‘and that without respect of any persons, as well to strangers and aliens as to many of this land, as well to poor as rich: whereof some looking for no redemption were by your gracious means not only freely delivered out of costly and very long imprisoning, but also by your charity largely rewarded and all things restored to the uttermost, so that every man may perceive

that your gracious and Christian mind is everywhere ready to help, succour and comfort them that be afflicted …’ Among the aliens she helped was Nicholas Bourbon de Vandoeuvre, a young French poet, ‘very zealous in the scriptures’, who was imprisoned for having ‘uttered certain talk in derogation of the bishop of Rome and his usurped authority’. Anne ‘did not only obtain by her grace’s means the King’s letters for his delivery but also after he was come into England his whole maintenance at the Queen’s only charge’.

This did not, of course, mean that all England was now friendly. More had not forgotten ‘the heretic Tyndale’. He described him, in a letter he wrote to Erasmus from Chelsea in mid-1533, as ‘a fellow Englishman, who is nowhere and yet everywhere …’. More was receiving reports from Antwerp; the agent sought by Vaughan, who was giving money to the friars Peto and Elstow, may have been looking for Tyndale on More’s behalf.

More was aware that Tyndale was not attending church, and taunted him for it. ‘As they say that know him,’ he wrote, ‘he sayeth none at all, neither matins, evensong, nor mass, nor cometh at no church but either to gaze or talk.’ It would have been more dangerous than ever for Tyndale to attend a service in 1533, when the local hue and cry against Lutherans was under way.

Tyndale kept himself well guarded in 1533 and deep into 1534. Stephen Vaughan, whose wife, interestingly enough, was one of Anne Boleyn’s silkwomen, reported to Cromwell from Antwerp on 21 October 1533 that Tyndale had been approached by opponents of the royal divorce. He was asked to work on a treatise condemning the Boleyn marriage, a task suspiciously similar to the one that Peto and Elstow were working on. He refused, Vaughan said, saying that ‘he would no farther meddle in his prince’s matter, nor would move his people against him, since it was done’.

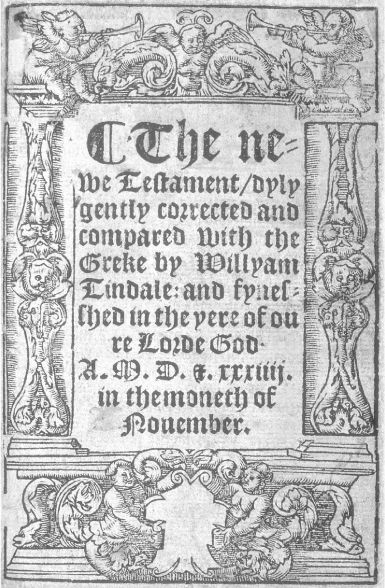

The title page of the 1534 revised New Testament. Tyndale was his own publisher, proofreader, editor, distributor and blurb-writer. He made more than five thousand changes to the 1526 edition. His description of the content is a gem of the copywriter’s art: ‘Here thou hast the newe Testament or covenaunt made wyth vs of God in Christes bloude.’

(British Library)

We know what Tyndale was doing at this time, if not precisely where he was doing it. He was revising Genesis and the New Testament. The new Genesis was printed in Roman letter rather than black Gothic. The glosses attacking the pope were removed, perhaps showing a greater confidence that reform might flourish in itself, rather than through the fury of its attacks on established Catholicism. The text was little changed from 1530, and it was sold bound into the other existing books of the Pentateuch.

The second edition of the New Testament was thoroughly revised, however, with more than five thousand changes. The new book had four hundred pages of black lettering with wide margins for references and comments. It was pocket-sized, 6 inches by 4, and comfortable to hold in the hand and read. This was not a lectern-sized tome designed to impress but a modern paperback-style book with vivid woodcuts that was intended to sell and to be read. The tales of apocalypse in Revelation, a favourite with readers, had twenty-two illustrations to increase their appeal.

The colophon was accurate, in order to distinguish it from a pirate revised edition that was in circulation. It read: ‘Imprinted at Antwerp by Martin Emperor Anno 1534.’ The printer was the Frenchman Martin Lempereur, whose main business was in French and Latin school texts and historical writings, and a series of French translations of Luther and Erasmus. He had became involved in English heretical writing from 1530. Although, as we have seen, he had a number of fake colophons, he was not fearful enough of the revised English Testament to use one of them.

The title page referred to the content as ‘diligently corrected and compared with the Greek, by William Tyndale’, and gave the date of publication as November 1534. All the books except Acts and Revelation had prologues. To a large extent, these were translations from Luther, although Tyndale added passages of his own which were sometimes at odds with the German. Luther felt that Hebrews and James were not apostolic. He had reason for doing

so – the origins of Hebrews remain obscure to modern scholars, and James, which Luther found a ‘right strawy epistle’, has a grounding in Greek culture that raises doubts about its authorship – but Tyndale insisted that they ‘ought of right be taken for Holy Scripture’.

The marginal notes were brief and explanatory. The pope and clergy did not escape scot-free. Where Paul urged the Thessalonians ‘to meddle with your own business, and to work with your own hands’, Tyndale could not resist a taunt from the margin: ‘A good lesson for monks and idle friars.’ In general, though, the usual ill-tempered assaults on the pope and clergy were missing.

At the back of the book Tyndale included forty passages from the Old Testament read out in services according to

Sarum Use

. This was the local medieval variation of the Roman rite used in the cathedral church of Salisbury, which became the standard for England. The reader thus had all the epistles heard through the year translated into English. For the most part, the Old Testament epistles came from the books that Tyndale had already translated. There was new material, however, from the Song of Songs, Zechariah, Joel and Malachi, and a haunting passage from Ecclesiasticus 24, lost to all those whose Protestant Bibles do not include the Apocrypha: ‘As a vine, so brought I forth a savour of sweetness. And my flowers are the fruit of glory and riches. I am the mother of beautiful love and of fear … In me is all trace of life and truth … Come unto me all that desire me, and be filled with the fruits that spring of me. For my spirit is sweeter than honey … They that eat me, shall hunger the more, and they that drink me, shall thirst the more …’

1

Tyndale described the book with a phrase worthy of any dust jacket. ‘Here thou hast (mooste deare reader)’, he began his introductory epistle, ‘the new testament or covenaunt made wyth us of God in Christes bloude.’ This was no dry priestly tome, but ‘glad

tydynges of mercie and grace, that oure corrupt nature shalbe healed agayne for Christes sake’; it was the guarantee of God’s gift of love, ‘loue overcomynge all payne, greffe, tedyousnesse or lothsomnes’.

He went on to claim that he had ‘weded oute of it many fautes, which lacke of helpe at the begynninge, and oversyght, dyd sowe therein’. He was helped by the experience of Hebrew he had gained with the Pentateuch, because there were Hebrew patterns of speech and ideas beneath the Greek in the New Testament, and he could now ‘consider the Hebrue phrase or manner of speche left in the Greke wordes’. For those who find faults, he declares, ‘it shalbe lawful to translate it themselves, and to put what they lust thereto’. If he himself agrees with any correction, then ‘I will shortlye after cause it to be mended’.

The row with More rumbled on. Tyndale explained why he would not change the words that were said to be offensive. ‘Repentance’ was right, he said, and the Catholic insistence on ‘penance’ was wrong. In the Old Testament, the Hebrew word

Sob

was generally used, meaning ‘turn or be converted’. The Greek in the New Testament ‘hath perpetually

metanoeo

to turn in heart and mynde, and to come to the ryght knowledge, and to a manne’s ryght wyt agayne’. Saint Jerome’s translation in the Vulgate, Tyndale insisted, should also be given as ‘repent’ in English. Jerome ‘hath some tyme

ago penetenciam

I do repent: sometimes

peniteo

I repent: sometime

peniteor

I am repentant …’. The ‘verye sense and significacion’ of both the Hebrew and Greek word ‘is, to be conuerted and to turne to God with all the hert’.

He said that repentance, ‘if it be unfeigned’, had four companions. Confession – ‘not in the preestes eare,’ he wrote of Catholic practice, ‘for that is but manne’s invencion’ – must take place to God in the heart. Then contrition, ‘sorrowfulness that we be such damnable synners’. Thirdly, faith, through which God for Christ’s sake ‘doth forgive us and receave us to mercie’, but of which the

doctors of the Church make ‘no mencion at all in the description of their penaunce’. Finally comes ‘satisfacion or amendesmakynge’, which is done ‘not to god with holye workes’, as More and the Church insisted, ‘but to my neyboure whome I have hurt, and the congregacion of God whome I have offended’.

The distinction between ‘repentance’ and ‘penance’ was more than wordplay. It was a matter of God’s meaning. Repentance to the evangelical involved private confession to God, and making amends, not to the Church, but to the whole ‘congregation of God’. It depended upon individual faith, for, as Tyndale wrote, ‘Christ saith Iohn viii “except ye believe that I am he, ye shall dye in your sinnes”’. To the Catholic, penance was impossible without the Church, and involved physical actions: auricular confession to a priest, taking part in a penitential procession or pilgrimage, the purchase of an indulgence, the carrying out of good works that met with the Church’s approval. To Tyndale, all this mattered nothing.

Tyndale was no pedant, and he did not mind what precise word was used. ‘Whether ye saye “repent”, “be converted”, “tourne to God”, “amende youre lyvynge” or what ye lust,’ he said, ‘I am content so ye understonde what is meant therby.’ It was meaning that was important. The same applied to the non-use of ‘priest’ that More had criticised. Tyndale replaced the ‘seniors’ of the 1526 Testament with ‘elders’ in the revised edition. He explained that the Old Testament used the word ‘elders’ for the Jews who ruled over the laity. From this custom, ‘Paule in his epistle and also Peter’ – the mention of Peter being a sly dig at the pope, with his claim to be the apostle’s successor – ‘call the prelates and spirituall gouernors which are byshoppes and preestes, “elders”’. He said that whether his readers called them ‘priests’ or ‘elders’ was ‘to me all one’, but he put a sting in the tail of this apparent concession. These were ‘offycers and servauntes of the worde of God’ whom all Christian men must obey, but only for ‘as long as they preache and rule trulye and no lenger’.

In the echoing passage of I Corinthians 13 – ‘Nowe abideth fayth, hope and love, even these thre: but the chefe of these is love’ – he refused to revise ‘love’ to ‘charity’. To have done so would have reverted to the Latin Vulgate, ‘

major horum est caritas

’, and to Wycliffe, ‘the moost of these is charite’. The English charity comes from

caritas

by way of the French

charité

. The Latin word derives from

carus

, dear. In the New Testament sense, so Tyndale insisted, it means ‘universal love’ and not its alternative of ‘good works’, or gifts, to the needy. It was the perceived insult to Catholic good works that led More to consider the use of ‘love’ to be heretical.

In the revision itself, he made an effort to correct the ‘errours committed in the prentynge’ of the 1526 edition. The misprints were numerous and indicated that the Worms compositors had no English. Sometimes they used a German spelling,

gebe

as in

geben

instead of

gave

, for example. No standard spellings existed in English, and it was common for a word to be spelt differently in a single passage: blessid, blessd, blesste and blest coexisted with blessed.

Simple misprints were of little concern – although he was at pains to restore ‘

Gog

’ to ‘

God

’ in a verse in John 8 – and he concentrated on errors that changed the meanings of words. In the same passage, he corrected

soone

to

sonne

, or son,

thaught

to

taught

, and

thought

to

though

,

stoppeth

to

steppeth

,

beloveth

to

beleveth

,

ynought

to

ynough

,

hat

to

hath.

His main aim was to strengthen his writing, to clarify meaning and to bring it closer to the Greek. He chose his words with great care, and his delicate editing is well seen in the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew’s gospel. He dropped the original ‘

blessed are the maynteyners of peace

’ for the more direct ‘

blessed are the peacemakers

’. He was unhappy with: ‘Ye are the salt of the earth; but and if

the salt be once unsavery

, what can be salted therwith.’ This was replaced by ‘if

the salt have lost her saltness

’, a charming phrase

that assigns a gender to salt. The passage continues: ‘It is thenceforthe goode for nothynge, but

to be caste oute at the dores, and that men treade it vnder fete

.’ This was replaced by the simpler and more rhythmic: ‘

to be caste oute, and to be troden vnder foote of men

’.