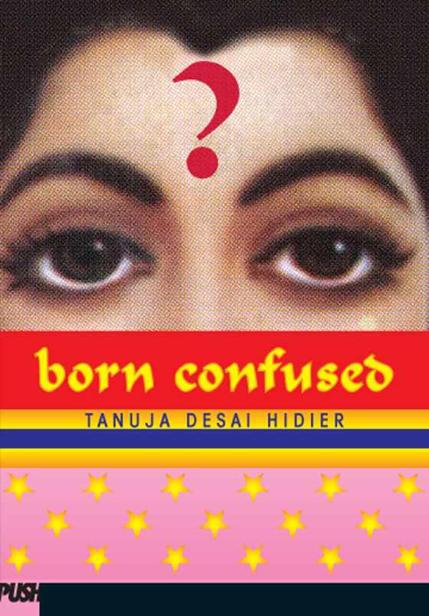

Born Confused

Tanuja Desai Hidier

For my Jeevansaathi, Bernard

(…flap, flap…)

“Some souls one will never discover, unless one

invents them first.”

—Friedrich Nietzsche,

Thus Spoke Zarathustra

I would believe only in a god who could dance.

—

ibid.

CHAPTER 1 the reincarnation of dimple rohitbhai lala the last

CHAPTER 3 the wish in your mouth

CHAPTER 6 the house of eternal diwali

CHAPTER 10 the most unsuitable suitable boy between the hudson and the ganges

CHAPTER 11 the world isn’t black and white

CHAPTER 17 in which the aunties and uncles throw it down

CHAPTER 20 and then there were three

CHAPTER 23 gur nalon ishq mitha

CHAPTER 27 subcontinental breakfast

CHAPTER 28 a brief history of love and laddoos

CHAPTER 31 walk like an indian

CHAPTER 33 homely girl seeking

CHAPTER 36 shree disco paradiso

CHAPTER 37 durga slays the demon

CHAPTER 39 thus dished zara thrustra

CHAPTER 43 the disorientation of dimple rohitbhai lala the first

the reincarnation of

dimple rohitbhai lala the last

I guess the whole mess started around my birthday. Amendment: my

first

birthday. I was born turned around, and apparently was holding my head in my hand in such a way that resulted in twelve treacherous hours of painful labor for my mother to eject me.

My mom said she imagined I was trying to sort out some great philosophical quandary, like Rodin’s

Thinker

sculpture that she had seen on a trip to Paris in another lifetime. But I think that was just a polite way of saying I looked like I didn’t get it. Born backwards and clueless. In other words, born confused.

So I came out the wrong way. And have been getting it all wrong ever since. I wished there was a way to go back and start over. But as my mother says, you can’t step in the same river twice.

This was going to be the first day of the rest of my life, Gwyn had announced to me on the way to school. After today: long hot months ahead, in which anything could—and would—happen. She said it with that insider wink that made it clear she had something up her sleeve, even though it was too hot for sleeves today and a silver armlet snaked a tantalizingly cool path round her biceps. The way she smiled mysteriously, mischievously at me was a surefire guarantee the heat was on in more ways than one.

And it was true the temperature was rising and there seemed to

be no end in sight. By second period, honors history, all my makeup had run off, even the so-called waterproof concealer; by third my thighs were welded together under the cramped desk; and by fourth my perm, which was supposed to have grown out months ago, resurrected itself with a vengeance, sending little ringlets Hula-Hooping out all over my head. There was a line for the fountain, and everyone was insatiable, sucking the water from the source, metal-lipped, which my mother says is unsanitary and very American. In fifth period, all the windows were cracked open to let in no wind, and a bead of sweat glittered on Mr. Linkhaus’s nose the entire hour, bobbing, teasing, but never falling.

No one was paying attention anyways. The only physics anyone was thinking about was how quickly a moving body could make it out the front door and into summer vacation. That is, everyone except me.

Now the last bell was ringing and I was staring into the upper shelf of my locker at Chica Tikka, my beloved camera. I was waiting for Gwyn, who’d called a ULP Wow (Urgent Locker Powwow), a little unnecessarily, considering we met up here every day after class; she had news for me, which was usually the case. And I was feeling lost without her, which was usually the case, too.

In our twosome I was “the other one”—you know, the one the boy doesn’t remember two seconds after delivering the pizza. The too-curvy, clumsy, camera-clacking wallflower with nothing but questions lately. But I guess you need someone with questions to give the one with all the answers an ear to inform, and maybe that was why we were together.

She had it all, Gwyn. And I had her, which by some sort of transitive theory gave me access to the allness she cupped in the palm of her hand. She even had the majority of my locker space, I realized now that I was unloading my own books and binders to find they’d

taken up minimum inchage. It was mostly her stuff here; we’d been sharing since I’d ended up with a more central A Hall locker, and in addition to her vinyl-coated books, she kept a makeup kit and hair serum in it. Pinned on the inside of the door, on either side of the black-and-white-and-many-greys image of a snowy peak in Yosemite that my Ketan Kaka had sent me, was a postcard of Marilyn Monroe losing her dress over a subway grating, and a calorie chart.

I took out Chica Tikka now, checking the counter. I still had a few shots left on this roll. I’d been taking black-and-whites all week, staying around late when Gwyn scooted off as usual to meet Dylan Reed, to whom she’d been joined at the lip for the last eternity.

I got disproportionately nostalgic at the end of the school year, not only for the good times but even, perversely, for my own misery, and took snap after shot of the empty hallways, bathrooms, classrooms. But no matter what I was trying to capture on film, if Gwyn was anywhere around, she always jumped in, drawn magnetic to the lens. I half-expected her to do so now, and even took off the lens cap to facilitate her entry, but it was a no-go.

I loaded up my knapsack, wondering if she’d forgotten about our meeting and was with Dylan now. Through my lens I was watching everyone’s jubilation, the happy clack of locker doors, the sign-my-yearbooks, the hallway hugs among people who never really seemed to hang before. Everyone was careening out to the buses, high-fiving each other; a few people said bye to me,

have a good one.

Even Jimmy Singh, whose real name was Trilok, nodded discreetly out from under his turban as he shufflingly followed his hawkish nose out.

I didn’t have to struggle for spy status. Fortunately I have this gift for invisibility, which comes in handy when you’re trying to take sneaky peeks at other people’s lives, and which is odd, considering I’m one of only two Indians in the whole school. The other being

the above-mentioned Jimmy (Trilok) Singh, who wore his ethnicity so brazenly, in the form of that pupil-shrinking turban and the silver kada bangle on his wrist, I got the feeling many people had stopped noticing that I hailed originally from the same general hood. But I did my best to play it down. After all, the day I wore my hair in braids everyone yelled

Hey, Pocahontas

and did that ahh-baah-baah-baah lip-slap at recess. You would have gotten a perm soon after as well.

Gwyn had gone with me to get the perm; in general, she often acted as my personal stylist, which served to disguise me still further (it was she who’d talked me into buying the too-tight tottery pumps I was now keeling in). In fact, I’d more often been mistaken, heritagically speaking, for Mexican than half-Mumbaite (a geographical personal status formerly known as half-Bombayite). But much as I tried to blend in—and much as I often did, with the wallpaper and floor if not the other kids—I still felt it sometimes, like when my mother came to Open House in that salvar khamees or when I stayed up all night trying to scrub the henna off my palms after Hush-Hush Aunty’s son’s wedding because during home ec Mrs. Plumb suspected I had a skin disease and refused to partake of my cinnamon apple crumble. And eating with my hands? I wouldn’t even do that at home, alone, and in the dark.

I don’t think it was always like this. My gift—or desire—for invisibility. Once again, I suppose it all began around my birthday. Not the one I was about to have in a couple days, my seventeenth, but the last one, when I turned sweet sixteen with no one to kiss because that afternoon Bobby O’Malley swiftly and unceremoniously dumped me on the way out to the late buses. I guess you can’t completely blame him; I mean, he’d forgotten it was my birthday, so it wasn’t like he did it out of any extraordinary mean streak. Just an ordinary quotidian kind of mean streak. It had been the beginning of a cruel summer, spent with my head in the fridge and my heart in the

garbage disposal. And when this year started, I couldn’t wait for it to be over, for school to be out so I wouldn’t have to see him anymore at all those dances that Gwyn insisted we go to, just to show him, who always ended up showing me by showing up with that batch of new girls, those thinner, prettier, blonder girls who ran their hands through his Irish curls and counted his freckles with their lips and were all hairlessly good in gym. My GPA dropped, mainly due to math, where I was unfortuitously seated next to Bobby (O having ended up next to L for Lala in that sad arrangement), but my Great Pound Average hefted up proportionately, about ten more slabs of flab. Gwyn insisted my scale wasn’t working, which was kind of her, but it was a state-of-the-art doctor’s scale from my father’s office, and I’d tested it against a couple of five-pound dumbbells that were collecting dust under my bed and which I used primarily for this purpose.

That day, I’d walked the final few steps out to the late bus in a daze. Gwyn (shockingly boyless at the time) was holding my seat for me, and I took it and whispered,

Bobby O’Malley just broke up with me.

Her mouth dropped open and I saw the wad of pink gum sunk in the center of her tongue. But she was good at quick saves, and firmly swallowed.

—Dimple Lala, you mark my words, she said.—That is the best birthday present B.O. could possibly have given you.

The rest of the ride she’d ranted out the top 101 reasons why he’d never been good enough for me in the first place (odd numbers are considered auspicious in India, and she’d become an ardent practitioner of that belief). She avoided the one about him secretly crushing on her, which was gracious.

But all I’d been able to think about was our nearly hundred kisses, the first fumbling one across the pond that separated our neighborhoods, in the then-unconstructed neighborhood near the

Fields where he pink-cheekedly brown-curledly lived, up to the ninety-eighth under the jungle gym at midnight. And the

I’ve never felt this way befores;

plenty of those were passed around the playground. And then, at that moment on that late bus, the feeling that forever actually had an expiration date, like a carton of milk, could go sour on you when you were least expecting it.

And since then every expired carton simply served to remind me of other sour times, every ending recalling all the ones before. Which maybe explained my sudden sadness today, the last day of junior year. It had been a particularly tough few terms; I’d had a lot of trouble with everything in the era A.B. (After Bobby) and especially this last year, when my grandfather Dadaji died, before any of us could get to him, freeze-framing my image of India in a fastescaping, ungrasped past. My mother had returned from Bombay with her accent newly thickened and her feeling that she should have never left as well, a growing desire to see me “settled.” I didn’t know what she meant, but I had the image of dust collecting pithily on a windowsill.