Born Survivors (43 page)

Authors: Wendy Holden

Survivors leaving KZ Mauthausen

There would have been little opportunity to appreciate for one last time the glorious scenery of that place where malevolence had pervaded all. Which one of them would have looked back at the forbidding walls of their last prison and reflected on what might have been if they hadn’t committed the mortal sin – in Nazi eyes – of being born to Jewish mothers? It wasn’t a time to look back but a time to look forward. As one of them said, ‘Now we could begin to live.’

With every breath since the day their tiny hearts started beating

in syncopation with those of their mothers, they could so easily have been destroyed.

Thousands of babies born during the Second World War didn’t make it.

Untold millions more never even had the chance to try.

In six years the Nazis had killed approximately two-thirds of the nine and a half million Jews living in Europe, as well as millions of non-Jews. Of almost one thousand women who had been loaded onto their train from Freiberg as well as those who’d joined their convoy, only half were definitively accounted for by the end of the war.

By a series of miracles, these three young women who’d been counted and then counted again by the Nazis over the years in

Appell

after

Appell

found themselves numbered amongst the living in the final roll call.

Thanks to courage, hope and luck, their babies were the first-ever prisoners of the camps to be given names instead of numbers. In defiance of those darkest of times, their legacy is that they are also inevitably destined to be the last-ever survivors of the Holocaust.

For them all, 1945 marked the end of something that would take years to come to terms with. But it also marked the birth of something countless generations would never experience – a new beginning and a chance to live and to love again.

Priska

The first passenger boat allowed on the River Danube after the war left the port of Enns and headed east on 19 May 1945, three weeks after the liberation of KZ Mauthausen. It sailed low in the water due to the numbers of refugees squeezed below decks, eager to get away. Among them was Priska Löwenbeinová.

The voyage was long, difficult and fraught with danger as the boat slowly made its way towards Vienna in the wake of a minesweeper that went ahead to check for unexploded bombs. The Nazis had seized control of the Danube after Hitler had declared it to be under German governance. Flotillas of warships from the Black Sea fleet patrolled Europe’s main waterway, protecting vital ports and firing anti-aircraft guns at Allied planes. Towards the end of the war, hundreds of those vessels were loaded with high explosives and deliberately scuttled in horizontal rows across the width of the Danube to slow advancing Soviet forces. These unstable underwater wrecks would continue to pose huge dangers to passing ships for decades to come.

A hundred and fifty kilometres from Mauthausen, Priska’s ferry was forced to stop at the historic town of Tulln, which had been heavily bombed because of its air base, refinery and railway bridge. The debris from the collapse of the bridge had made the river temporarily impassable and had to be cleared. For two days the boat, with its bedraggled cargo sleeping on straw, had to moor on the riverbank on the westerly side of Tulln. The unexpected delay further frayed survivors’ nerves by detaining them in the nation of Hitler’s birth. Some couldn’t stand the wait and insisted on disembarking. Heading east on foot and travelling light, they stumbled into the town to catch trains to Vienna and beyond, paying for their tickets with American cigarettes which had become as valuable as gold.

With a baby in her care Priska was far less flexible, so she stayed on board and waited for the riverbed to be cleared before the boat could ferry them home. When she finally disembarked at Zimný Prístav (The Winter Harbour) in Bratislava on 22 May, she found that although the town had been bombed, its historic centre had survived largely unscathed. She longed to hurry straight to their apartment to see if Tibor was waiting, but her first priority was Hana, who once again needed urgent medical care. Her wounds had reopened on the journey, soaking her bandages in blood.

Afraid that she should have heeded Major Stacy’s advice, Priska rushed her daughter straight to the Children’s Hospital in Duklianska Street, where paediatrician Professor Chura took one look at the severely malnourished baby covered in open sores and announced that he would have to operate immediately. For the second time in a matter of weeks, Hana underwent emergency surgery to lance and clean out the multiple abscesses caused by a serious deficiency of vitamins. Then the doctor stitched her up again and admitted her to a specialist ward.

Priska waited anxiously for news of an improvement and prayed for Hana’s survival. ‘I had a good feeling because she wanted to live – she really wanted to live,’ she said later. Professor Chura said the same words to Priska when he emerged from the operating theatre.

Once the surgery was declared a success and Hana was out of danger, her half-starved mother was taken to the kitchens by two of the nuns who ran the hospital. Looking around hungrily, she noticed a pot on the stove containing cooked beans in a kind of stew. Before anyone could say anything, she grabbed the pot and literally drank the whole lot down, as people watched in ‘deafening silence’.

‘No one stopped me or said a word,’ she said. ‘I was so hungry.’

Realising that Priska, too, needed their care, the nuns offered her a place to stay until Hana was well enough to be released and she’d regained her strength. She accepted gratefully and remained in their care for two weeks. After resting, and leaving Hana sleeping, she finally returned to the place she believed Tibor would head for – their old apartment at Fisherman’s Gate. She was shattered to discover that it was one of the few buildings in the old town that had taken a direct hit. She found only rubble. Devastated, she kicked around in the debris and could hardly believe it when she came across one of Tibor’s precious notebooks, his handwriting distinctive albeit smeared with dirt. She kept it like a talisman until her death.

Huge noticeboards had been erected in the centre of Bratislava by the Jewish community and others in order for people to leave messages for their loved ones, so Priska wrote that she and the baby had survived and gave the address of the hospital. Then she went back there to wait for Tibor and anyone else who might have made it. As the days and weeks passed, friends and family began to drift back into town, including her younger sister Anička (Little Anna) and her uncle, Dr Gejza Friedman, with whom Anna had sought refuge in the Tatra Mountains. Her grandfather had survived the Nazi purges but sadly had then died after accidentally falling from a window. Uncle Gejza suggested that they all find a place to live together. In time, Hana would come to adore her uncle ‘Apu’, the only father-figure in her life, and Priska thought of Gejza as a surrogate father too, especially in the absence of her own parents.

Her brother Bandi sent word from Mandatory Palestine that he was well, married, and had a stepdaughter. Amazingly, her other

brother Janko soon reappeared, having fought bravely with the partisans. His hair had grown to his shoulders and the boy who’d left them returned a man. Thanks to his war record, he was afforded all kinds of privileges, including his pick of the city’s accommodation, and the first thing he did was take Priska the keys to four large apartments that he and his family could choose from. These flats had almost certainly once belonged to Jewish families who were never coming home. Priska refused to inhabit ‘dead man’s shoes’ and was determined not to move any distance from where she used to live, so that Tibor could still find her.

Weeks passed with no sign of her parents, Emanuel and Paula Rona, proud coffee shop owners from Zlaté Moravce, deported to Auschwitz in July 1942. She learned from family friends much later that her mother and father had been gassed within a month of their arrival at Birkenau. Nor did her thirty-four-year-old sister Boežka come back, the spinster whom Priska had tried to rescue from a transport that March. Years later, she learned that Boežka had been saved from the gas chambers for her talents as a seamstress and put in charge of the sewing department in Auschwitz. For three years she made and repaired uniforms and other garments for the SS. At risk to her own life, Boežka was kind to the girls who worked under her and turned a blind eye when they secretly patched what they and others had been given to wear. In one unreliable report, Priska was broken-hearted to hear that in December 1944, a month before the camp was liberated, Boežka was said to have run at the live fence and killed herself. Later though a woman who’d known her well in the camp said this wasn’t true and she’d contracted typhoid, which killed her. Priska chose to believe the second version.

Weeks turned to months, but still there was no word of Tibor and no sight of him in the street, as Priska had always imagined there would be. She felt herself to be in a netherworld in which she was unable to move away or even go back to see what might be left in Zlaté Moravce in case she missed him. With a sickly baby to care for, she couldn’t work and had no money. Nor did she know what

would happen in her country. Although Czechoslovakia had been reconstituted and former Slovak President Monsignor Jozef Tiso hanged for his collaboration with the Nazis, eighty per cent of its Jews had been exterminated and the nation’s future under the Communists was still deeply uncertain.

After a couple of weeks living in the hospital and with the little money she’d been given by the Red Cross, as well as some from her uncle, she took rooms near their old apartment so that she could walk there at least once a day to see if her husband was waiting. Their new rooms were in the second-floor servants’ quarters at the back of a grand three-storey building on Hviezdoslav Square. Damp and rat-infested, they comprised a small bedroom, a living room, and a kitchen in which she set up a bathtub.

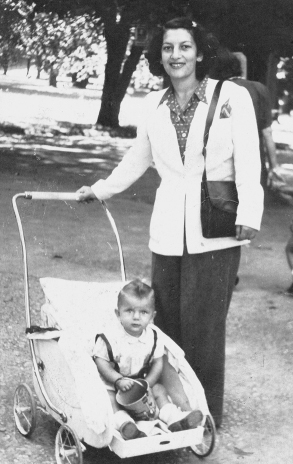

Hana and her mother Priska 1946

One day, pushing Hana along the street in her buggy to the public noticeboard to see if there were any new messages, Priska bumped into a man named Mr Szüsz whom she had known before the war. He greeted her warmly before telling her that he’d been with Tibor in the camps. From Auschwitz, he said, they had been among 1,300 men transported to the satellite slave labour camp at Gliwice (by the Germans Gleiwitz), some twenty kilometres away, where prisoners were forced into brick manufacture, construction, or freight wagon repair for the Nazi railway workshop known as the

Reichsbahnausbesserungswerk

. Then Mr Szüsz broke the news to Priska that her husband wasn’t coming back. ‘He didn’t believe you and the baby would survive,’ he told her, as her mind grappled with what he was trying to tell her. ‘He stopped eating and became too weak to care for himself. He would say, “I don’t want to live any more. What is life worth without my wife and child?”’

Priska, who tried to sift through his words and search for their meaning, eventually stumbled blindly away from Mr Szüsz to grieve in private. Her mind torn, she was never able to find out the precise details of Tibor’s death. Eventually, through testimonies from other survivors and people who knew him, she discovered as much as she needed to know. In the bitter cold of January 1945, with temperatures down to minus twenty, the 1,300 or so half-starved prisoners of Gliwice, wearing pyjamas and wooden shoes, were forced on a death march to the huge synthetic fuels plant at Blechhammer, forty kilometres away. In close formation, they were ordered to march with the warning that all stragglers would be shot. Through snow and ice they walked, eventually joining a snaking rope of 4,000 creatures that crunched on towards Gross-Rosen, one of the last remaining concentration camps, a distance of almost two hundred kilometres. Theirs proved to be one of the most notorious of all the death marches. Hundreds of prisoners in threadbare striped uniforms whose bones could no longer carry them were shot on the spot. Their bodies were dragged from the road and thrown into ditches, out of sight.

‘Tibor simply gave up,’ Priska was told by one who’d survived the

march. ‘He died of hunger at the end of January 1945 … He fell by the side of the road and that’s where he remained … He was probably shot.’

Tibor Löwenbein, the smiling, pipe-smoking, journalist, bank clerk, husband and father, had perished in an unknown location on the side of an icy road in Silesia, Poland, just a few months before the end of the war at the age of twenty-nine. There was no body to weep over or for Priska to say

kaddish

for. There would be no funeral, no grave marker on which to lay stones, on which to light a candle on

yahrzeit

, the anniversary of his passing. In fact, there would be no ritual farewell at all – Jewish or otherwise.

His widow never recovered from his death. For the rest of her days, she refused to remarry. ‘I had a great marriage with my husband,’ she said. ‘I stayed alone because I couldn’t live with anyone else or find anyone else like him.’