Borrowed Time (46 page)

“I quite understand.”

“My name’s Hyslop. Chief Inspector Hyslop, Sussex Police.” He looked about forty, with thinning hair combed forward in a style Charlotte disliked, but there was a winning edge of confusion to his features and a schoolboyish clumsiness about his dress that made her feel it should be her putting him at his ease, not the other way about at all. “How did you hear about this?”

“Maurice—Maurice Abberley, that is, my half-brother—telephoned me. I gather Mrs. Mentiply found . . . what had happened.”

“Yes. We’ve just sent her home. She was a bit upset.”

“She’d worked for Miss Abberley a long time.”

“Understandable, then.”

“Can you tell me . . . what you’ve learned?”

“Looks like a thief broke in last night and was disturbed while helping himself to the contents of”—he pointed across the room—“that cabinet.”

Turning, Charlotte saw for the first time that the glass-fronted cabinet in the corner was empty and that its doors were standing open, one of them sagging on its hinges.

“Full of wooden trinkets, according to Mrs. Mentiply.”

“Tunbridge Ware, actually.”

“I’m sorry?”

“It’s a special form of mosaic woodwork. The craft has long since died out. Beatrix—Miss Abberley—was an avid collector.”

“Valuable?”

“I should say so. She had some pieces by Russell. He was just about the foremost exponent of . . . Ah, the work-table is still here. That’s something, I suppose.”

In the opposite corner, beside a bookcase, stood Beatrix’s prize example of Tunbridge Ware: an elegantly turned satinwood work-table complete with drawers, hinged flaps either side of the leather-covered top and a silk work-bag beneath. All the wooden surfaces, including the legs, were decorated with a distinctive cube-patterned mosaic. Though it was not this but the array of mother-of-pearl sewing requisites kept in the pink silk-lined drawers that Charlotte remembered being fascinated by in her childhood.

“The effect is produced by applying a veneer of several different kinds of wood,” she said absently. “Highly labour-intensive, of course, especially on the smaller pieces. I suppose that’s why it died out.”

“I’ve never heard of it,” said Hyslop. “But we have an officer who specializes in this kind of thing. It’ll mean more to him. Mrs. Mentiply said the cabinet contained tea-caddies, snuff boxes, paper-knives and so forth. Is that your recollection?”

“Yes.”

“She agreed to draw up a list. Perhaps you could go over it with her. Make sure she leaves nothing out.”

“Certainly.”

“You say this stuff is worth a bit?”

“Several thousand pounds at least, I should think. Possibly a lot more. I’m not sure. Prices have been shooting up lately.”

“Well, we can assume our man knew that.”

“You think he came specifically for the Tunbridge Ware?”

“Looks like it. Nothing else has been touched. Of course, the fact he was disturbed may account for that. It would explain why he left the work-table behind. If he was in a panic to be away, he’d only have taken what was light and portable. And he would have been in a panic—after what happened.”

Charlotte gazed around the room. Aside from the empty cabinet, all else seemed intact, preserved in perfect accordance with her memory of so many tea-time conversations. Even the clock on the mantelpiece ticked to the same recollected note, last wound—she supposed—by Beatrix. “Where did it . . .” she began. Then, as her glance moved along the mantelpiece, one other change leapt out to seize her attention. “There’s a candlestick missing,” she said.

“Not missing, I’m afraid,” said Hyslop. “It was the murder weapon.”

“Oh, God. He . . . hit her with it?”

“Yes. About the head. If it’s any consolation, the pathologist thinks it must have been a quick exit.”

“Did it happen here—in this room?”

“No. On the landing upstairs. She’d got out of bed, presumably because she’d heard him down here. He seems to have climbed in through one of these windows. None of them would have given a professional burglar much trouble and that one there”—he pointed to the left-hand side of the bay—“was unfastened when we arrived, with signs of gouging round the frame, probably by a jemmy. Anyway, we can assume he heard her moving about upstairs, armed himself with the candlestick and went up to meet her. He probably didn’t intend to kill her at that point. She had a torch. We found it lying on the landing floor. Perhaps he panicked when she shone it at him. Perhaps he’s just the ruthless sort. There are a lot of them about these days, I’m afraid.”

“This was last night?”

“Yes. We don’t know the exact time of death yet, of course, but we reckon it was in the early hours. Miss Abberley was in her night-dress. The curtains in her bedroom, in the bathroom and down here were all closed. They stayed that way until Mrs. Mentiply arrived at half past four this afternoon.”

“What made her call? She doesn’t usually come in on Sundays.”

“Your—half-brother did you say?—Mr. Maurice Abberley. He’d telephoned his aunt several times and become concerned because there was no answer. She’d told him she’d be in, apparently. He lives quite some way away, I believe.”

“Bourne End. Buckinghamshire.”

“That’s it. Well, to put his mind at rest, he telephoned Mrs. Mentiply and asked her to look round. I’ll need to confirm her account with him when he arrives, of course. You live somewhat nearer yourself?”

“Tunbridge Wells.”

“Really?” Hyslop raised his eyebrows in sudden interest.

“Yes. I suppose that’s why I know so much about Tunbridge Ware. It’s a local speciality. There’s a very good collection in the—”

“Does the name Fairfax-Vane mean anything to you, Miss Ladram?”

“No. Should it?”

“Take a look at this.” He opened his pocket-book, slid out a small plastic bag enclosing a card and passed it to her. Set out boldly across the card in Gothic script was the heading

THE TREASURE TROVE

and beneath it, in smaller type:

COLIN FAIRFAX-VANE

,

ANTIQUE DEALER

&

VALUER

,

IA CHAPEL PLACE

,

TUNBRIDGE WELLS

,

KENT TNI IYQ

,

TEL

. (0892) 662773. “Recognize the name now?”

“I know the shop, I think. Hold on. Yes, I do know the name. How did you come by this, Chief Inspector?”

“We found it in the drawer of the telephone table in the hall. Mrs. Mentiply remembered the name as that of an antique dealer who called here about a month ago, claiming to have been asked by Miss Abberley to value some items. But Miss Abberley hadn’t asked him, it seems. She turned him away, though not before Mrs. Mentiply—who was here at the time—had shown him into this room, giving him the chance to run his eye over the Tunbridge Ware. Now, how do you know him, Miss Ladram?”

“Through my mother. She sold some furniture to this man about eighteen months ago. As a matter of fact, Maurice and I both felt she’d been swindled.” And had bullied her remorselessly on account of it, Charlotte guiltily recalled.

“So, Fairfax-Vane is something of a smart operator, is he?”

“I wouldn’t know. I’ve never met the man. But certainly my mother . . . Well, she was easily influenced. Gullible, I suppose you’d say.”

“Unlike Miss Abberley?”

“Yes. Unlike Beatrix.”

“You don’t suppose your mother could have told Fairfax-Vane about Miss Abberley’s collection?”

“Possibly. She knew of it, as we all did. But it’s too late to ask her now. My mother died last autumn.”

“My condolences, Miss Ladram. Your family’s been hard hit of late, it appears.”

“Yes. It has. But— You surely don’t suppose Fairfax-Vane did this just to lay his hands on some Tunbridge Ware?”

“I suppose nothing at this stage. It’s simply the most obvious line of inquiry to follow.” Hyslop made a cautious attempt at a smile. “To expedite matters, however, we need a definitive list of the missing items with as full a description as possible. I wonder if I could ask you to find out what progress Mrs. Mentiply has made.”

“I’ll go and see her straightaway, Chief Inspector. I’m sure we can let you have what you need later this evening.”

“That would be excellent.”

“I’ll be off then.” With that—and the chilling thought that she was glad of an excuse not to go upstairs—Charlotte rose and headed for the hall. She turned back at the front door to find Hyslop close behind her.

“Your assistance is much appreciated, Miss Ladram.”

“It’s the least I can do, Chief Inspector. Beatrix was my godmother—and also somebody I admired a great deal. That this should happen to her is . . . quite awful.”

“Sister of the poet Tristram Abberley, I understand.”

“That’s right. Do you know his work?”

Hyslop grimaced. “Had to study it at school. Not my cup of tea, to be honest. Too obscure for my taste.”

“And for many people’s.”

“I was surprised to find he had a sister still living. Surely he died before the war.”

“Yes. But he died young. In Spain. He was a volunteer in the Republican army during the Civil War.”

“That’s right. Of course he was. A hero’s end.”

“So I believe. And yet a more peaceful one than his sister’s. Isn’t that strange?”

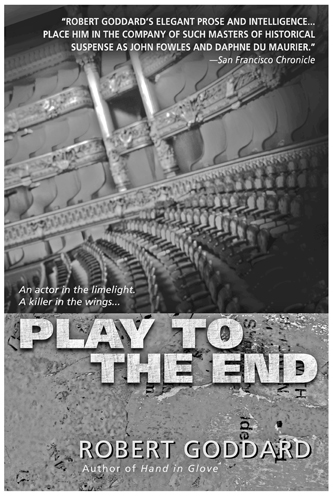

PLAY TO THE END

Actor Toby Flood arrives in the seaside town of Brighton to perform in a touring production of a recently discovered farce,

Lodger in the Throat

. When he is visited by his estranged wife, Jenny, who insists she is being followed by a strange man, Toby finds himself caught up in a mysterious and dangerous tangle of family rivalries and murderous intent.

W

hat I felt as I got off the train this afternoon wasn’t what I’d expected to feel. The journey had been as grim as I suppose it was bound to be on a December Sunday. Most of the others had chosen to go via London and they won’t be coming down here until tomorrow. I could have joined them. Instead I volunteered for the slow South Central shuffle along the coast. I had plenty of opportunity to analyse my state of mind as a seamless succession of drab back gardens drifted past the grimy train window. I knew why I hadn’t gone up to London, of course. I knew exactly why bright lights and brash company weren’t what the doctor had ordered. The truth is that if I

had

fled to the big city, I might never have made it to Brighton at all. I might have opted out of the last week of this ever more desperate tour and let Gauntlett sue me if he could be bothered to. So, I came the only way I could be sure would get me here. Which it did. Late, cold and depressed. But

here.

And then, as I stepped out onto the platform—

That feeling is why I’m talking into this machine. I can’t quite describe it. Not foreboding, exactly. Not excitement. Not even anticipation. Something slipping between all three, I suppose. A thrill; a shiver; a prickling of the hairs on the back of the neck; a ghost tiptoeing across my grave. There wasn’t supposed to be anything but a protraction of a big disappointment waiting for me in Brighton. But already, before I’d even cleared the ticket barrier, I sensed strongly enough for certainty that there was more than that preparing a welcome for me. More that might be better or worse, but, either way, was preferable.

I didn’t trust the sensation, of course. Why would I? I do now, though. Because it’s already started to happen. Maybe I should have realized sooner that the tour was a journey. And this is journey’s end.

The tapes were my agent’s idea. Well, a diary was what she actually suggested, back in those bright summer days when this donkey of a play looked like a stallion that could run and run and the mere prospect merited a lunch at the River Café. A chronicle of how actors refine their roles and discover the deeper profundities of a script before they reach the West End is what Moira had in mind. She reckoned there might be a newspaper serialization in it to supplement the two thou a week Gauntlett is ever more reluctantly paying me. It sounded good. (A lot of what Moira says does.) I bought this pocket audio doodad on the strength of it, while the Cloudy Bay was still swirling around my thought processes. I’m glad I did now.

But it’s more or less the first time I have been. I abandoned the diary before I’d even started it, up in Guildford, where the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre hosted the world premiere of our proud production. Is it only nine weeks ago? It feels more like nine months, the span of a difficult pregnancy, with a stillbirth the foregone conclusion since we had word from Gauntlett that there was to be no West End transfer. I thank God for the panto season, without which he might have been tempted to keep us on the road in the hopes of some magical improvement. As it is, the curtain comes down next Saturday and seems likely to stay there.

It shouldn’t have turned out this way. When it was announced last year that a previously unknown play by the late and lauded Joe Orton had been discovered, it was widely assumed to be a masterpiece on no other basis than its authorship. What greater proof was needed, after all? This was the man who gave us

Entertaining Mr. Sloane, Loot

and

What the Butler Saw.

This was also the man who sealed his reputation as an anarchic genius by dying young, murdered by his lover, Kenneth Halliwell, at their flat in Islington in August 1967. I have all the facts of his extraordinary life at my fingertips thanks to carting his biography and an edition of his diaries around with me. I thought they might inspire me. I thought lots of things. None of them have quite worked out.