BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (10 page)

Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

O’Brien landed the first punches. First thing that morning, his deputies began arresting Republican vote-watchers. They started with James Dennis, an uptown inspector who apparently had a list of one hundred and fifty ‘repeaters’ who intended to vote and whom he intended to challenge. The deputies stopped him at his house, handcuffed him and dragged him off to Ludlow Street Jail. They arrested at least two more inspectors and then circulated to polling places around town, bullying any others who challenged a Tammany ballot. Then came swarms of repeaters; some deputies actually escorted them from poll to poll to prevent interference. At Spring and Varrick Streets, for instance, one Tammany deputy pulled a revolver on a policeman trying to arrest him for fighting; the officer too pulled a gun and for several moments each threatened to shoot the other until finally the deputy backed down.

60

After sundown, when the polls closed, Tammany’s inspectors played havoc with the count, giving its backroom fixers time to manufacture whatever numbers they needed. In the Thirteenth ward, for instance, just as the ballot box was being opened, a group identified only as “ruffians” reportedly “turned off the gas, leaving the room in darkness” and “before the lights could be procured many of the tickets were removed and others mixed with those lying on the table.” In other wards, Democratic counters allegedly haggled for hours on technicalities or insisted on reading every name on every identical ticket, all to delay the counts.

61

Robert Murray, the U.S. marshal, made his own arrests that day, he and his men carting off dozens of Tammany braves for trying to cast illegal votes, many with fake citizenship papers. But he couldn’t hold them long in jail; Tammany sent squads of lawyers to friendly judges who quickly began to free them. George Barnard of the state Supreme Court issued one

habeas corpus writ

that released twenty-seven with a single flash of his pen.

Tweed himself spent election night celebrating at the Metropolitan Hotel. When the dust settled, they’d won John Hoffman the governorship by more than 47,000 votes, making a mockery of Horatio Seymour’s mere 10,000-vote statewide margin over Grant. Tweed himself won reelection as county supervisor, and Barnard as supreme court judge, both by huge margins. Even a Republican stalwart like E.L. Godkin, editor of

The Nation

—a rapidly anti-Tammany journal—found the spectacle irresistible: “I want very much to show ‘the unterrified’ in their glory to two English friends tonight at Tammany Hall,” he wrote to Manton Marble during the day, “& write to ask whether you could kindly put me in the way of getting three tickets” to the celebration.

62

Tweed could be especially satisfied with his new front man. John Hoffman, the new governor, a Union College graduate who’d been popular as mayor, independent, and apparently honest. “He was not approachable with money,” Tweed himself would later claim, both with pride and lament.

63

Come 1872, four years from now, Hoffman would be a strong challenger for the White House against Ulysses Grant. Using Tammany ballot-box tactics coast to coast, how could they loose? Tweed himself stood to become a national power.

F

OOTNOTE

Now, as he sat before the congressional investigating committee in the federal courthouse on Chambers Street answering questions about the alleged election frauds, Tweed could be gracious. A former congressman himself, he knew how to talk turkey with the committee. Confronted with specific charges of fraud, he claimed ignorance. “O, I hear rumors on every subject,” he shrugged. “Everything you have asked me there have been rumors about, of course. I have heard them in the general rumble of city politics and city conversation.” He had nothing to say about the Tilden letter; asked if he knew about Benjamin Rosenberg and illegal citizenship papers, he said simply: “No sir; I do not.”

64

The congressmen accepted Tweed’s word at face value, just as they’d done with Samuel Tilden earlier that morning. Tweed charmed them: “I was born in New York and have lived here all my life, and have as many friends among republicans as among democrats,” he recounted. He joked about the money he’d personally sunk into the campaign: “Perhaps I contributed entirely about $10,000… I subscribed $5,000 to the State committee and the rest went out in driblets after that.”

65

Asked if he had city street employees drawing salaries but doing no actual work—political “sinecures”—he hardly bothered to deny it: “I don’t suppose that I have been through the [street department] building more than twice a year; but I know that when I send for them during business hours I usually find them.”

66

In the end, Tammany Hall itself recognized the biggest winner in the episode. On March 5, 1869, it unanimously elected Tweed its new Grand Sachem—taking the seat vacated by John Hoffman, the new governor—making Tweed simultaneously both its symbolic and its actual chief, a leader of whom they could say “no one really in need ever turned away from him empty handed.”

67

As for the voting itself and the forged letter from Samuel Tilden, Tweed only years later would suggest he knew more than he’d let on in his easy denials to the congressmen that day. “The ballots didn’t make the outcome. The counters did,” he’d say cryptically.

68

-------------------------

The congressional committee issued its final report on the 1868 New York voting in February 1869. By then, its members had heard from 417 witnesses—a dizzying parade of thugs, policemen, and backroom fixers—and the drama in the federal courthouse on Chambers Street had degenerated into strong-arm tactics and finger pointing. Jimmy O’Brien sent his deputy sheriffs one day in early January to arrest seven witnesses waiting in the lobby to testify and drag them off to a nearby police station; the next day, Metropolitan police officers came too, this time to eject the deputy sheriffs and post guards at the committee’s meeting room until Democrats insisted that they too leave.

In its conclusion, the committee found the 1868 election to have been grossly manipulated. “The frauds were the result of a systematic plan of gigantic proportions, stealthily prearranged and boldly executed, not merely by bands of degraded desperadoes, but with the direct sanction, approval, or aid of many prominent officials and citizens of New York,” it claimed, and was “aided by an immense, corrupt, and corrupting official patronage and power, which not only encouraged, but shielded and protected, the guilty principals and their aiders and abetters [sic.].”

69

Of the 156,054 votes cast in New York City that year, the committee estimated that 50,000 had been fake or illegal, the product of repeat voting, illegal naturalizations, or fictitious counts. The total votes cast in New York City that year had exceeded the number of possible voters—actual human beings of voting age and gender—by more than 8 percent.

70

Hoffman’s election as governor was a fraud, they charged, as was Seymour’s carrying of the state.

But beneath these splashy headlines, the investigation produced few specifics: It recommended no prosecutions and proposed only a handful of generic reforms such as stripping New York courts of their power to grant citizenships and passing a constitutional amendment allowing Congress to regulate the appointment of presidential electors.

71

The

New York Herald

dismissed the whole effort as “a hifalutin and long-winded peroration of a bitter partisan character” with “no direct evidence of such extensive frauds.”

72

The

New York World

labeled it simply “A Stock of Stale Slanders.”

73

Other than Benjamin Rosenberg—caught red-handed selling fake citizenship papers to the U.S. marshal—no one was ever convicted of a crime for the 1868 voting scandal. In New York City, Judge Barnard convened a grand jury to pursue violations of local laws, but the jury—which included eleven Tammany members out of twenty jurors—discovered none.

74

The fraud charges, it concluded, were “manifestly unfounded … except those which ordinarily arise in any excited political contest, and which are comparatively trivial.”

75

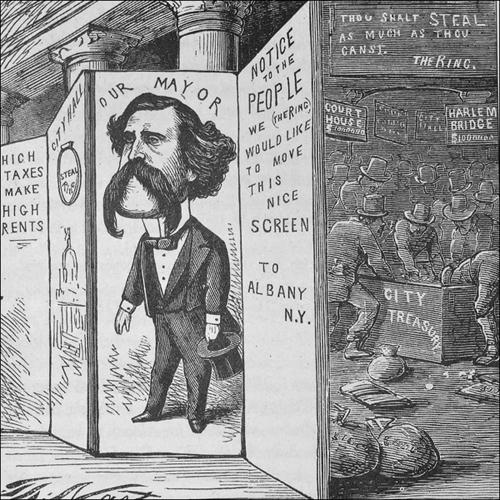

“A Respectable Screen Covers a Multitude of Thieves.”

Harper’s Weekly, October 10, 1868.

For Tammany it looked like a clean getaway: griping by the losers but no serious challenge to the result and no lasting mud on its skirts. In fact, in the celebrating, only one small cloud appeared to block the sunshine and cast a shadow on the scene: Shortly after Election Day, a small cartoon appeared on a back page of

Harper’s Weekly

, the popular illustrated magazine. “A respectable screen covers a multitude of thieves,” its caption read. It showed the figure of John Hoffman, looking handsome and smug with his signature handlebar mustache, “Our Mayor,” a proud smirk on his face, drawn onto a large stand-up screen placed in a position to block the sight behind it of several grubby-looking men taking fistfuls of cash from a box labeled “city treasury.” Over the men hung a sign that read: “Thou shalt steal as much as thou canst. The Ring.”

Tweed himself probably saw the cartoon and may have snickered at the satire. He would have noticed the signature in small neat letters at the bottom corner: “

Th. Nast

.” But it wouldn’t have bothered him. None of the “Ring” figures in the cartoon had a recognizable face and the drawing gave no details—it made only a vague charge. Still, Tweed had to wonder: Did this “

Th. Nast

” really know anything? Probably not. Hearsay aside, Tweed knew he kept his secrets carefully. And it was just a cartoon. What difference could it make?

CHAPTER 4

SPOILS

“ I think … that a great injustice has been done me. I have been charged with breaking the pledge I made… I deny that, during the whole course of my life, I have ever broken any pledge made by me to either friend or foe. Whatever else there might be in my conduct to censure or find fault with, I HAVE ALWAYS KEPT MY WORD….

—

TWEED

, to a private caucus of so-called Young Democrat rivals in the state legislature in Albany.

New York Sun

, March 26, 1870.

“ Tweed was not an honest politician, but a level one—Kelly is honest but not level.”

—

S. FOSTER DEWEY

, Tweed’s secretary, on Tweed’s death, comparing Tweed to his Tammany successor “Honest John” Kelly, April 12, 1878.

1

On New Year’s Day, January 1, 1869, Abraham Oakey Hall swore the oath to become New York City’s new mayor. He now took the place of former mayor John T. Hoffman—who’d left for Albany to become the state’s new governor—at the daily “lunch club” at City Hall. The lunch group now included Hall, city chamberlain Peter Sweeny, comptroller Richard Connolly, and Tweed wearing his many hats—state senator, deputy street commissioner, and boss of Tammany. These four men now controlled almost every key lever of power in New York City, with a tightening grip on the state government in Albany:

City Hall, through the mayor;

The city and county treasuries, through Connolly as comptroller;

The law, through Tammany judges like George Barnard, sheriff O’Brien, and a friendly police board;

Wall Street, through Jay Gould, Jim Fisk, and the Erie Railway;

The state legislature, through Tweed as senator and Hoffman as governor;

The newspapers, through advertising, flattery, and ownership.

They could reward friends with jobs and contracts and punish enemies with a cold shoulder, and they had backers by the thousands, people ready to trust them and do their bidding. They’d proven they could always win elections and they’d grown very rich.

The reign of the Tweed Ring at its height of power, started here.

-------------------------

N

EW Yorkers waking up on the first day of the Tweed era in 1869 would notice one immediate difference in their noisy city—a flamboyant new mayor. “Elegant Oakey,” that’s what his friends called him for his dapper suits and comic airs. He rarely had enemies; everyone liked him, even men he’d sent to prison. Witty and urbane, he often signed his name “OK” and wore his pretensions on his sleeve. He wrote literary essays for local journals and dramas for the New York stage. “I’ve been called the king of the Bohemians,” he once quipped, “and I’m jolly proud of that title.”

2

Skinny with narrow eyes, pince-nez glasses, and full beard, he proudly traced his ancestry to Coll Okey, an Englishman hanged in 1662 for his role in the execution of King Charles I—a favorite point with Irish voters. Born in Albany, raised in New Orleans, educated at Harvard Law School, Hall had won elections as New York’s district attorney consistently since 1853—first as a Whig, then a Republican, then a Mozart Hall Democrat, then a Tammany Hall Democrat.

He lived with his wife Katherine “Kate” Louise Barnes Hall—daughter of marble magnate Joseph Barnes—in a large brownstone on West 42nd Street across from the Croton Reservoir

F

OOTNOTE

with their son and five teenage daughters. Oakey joined every club—he traded gourmet tips with the Manhattan Club’s famous chef, led dialogues on literature at the Lotus Club, and easily made “the list,” New York’s earliest Social Register. He’d joined Tammany during the Civil War, drawn as much by ambition as by distaste for that uncouth Republican backwoodsman Abe Lincoln in the White House. He’d signed the Tammany membership log with a flourish: “Whilst Council fires hold out to burn, The vilest sinner may return. OK.”

3

As district attorney, Hall craved the limelight. He took credit for arguing 10,000 cases before juries and sent legions of criminals to jail—from Civil War draft rioters to murderers and pickpockets to gang members and political crooks. But he was equally famous for the 10,000 other indictments he’d chosen to ignore, mostly liquor law violations. “Somehow or other the press of business in my office has been so great that I have never yet found time to prosecute a man for taking a drink after 12 o’clock at night,” he once quipped.

4

Saloonkeepers loved him. “Few persons have as many

tried

friends as I have,” he bragged after one election victory with a trademark pun, “and

tried

friends are always magnanimous.”

5

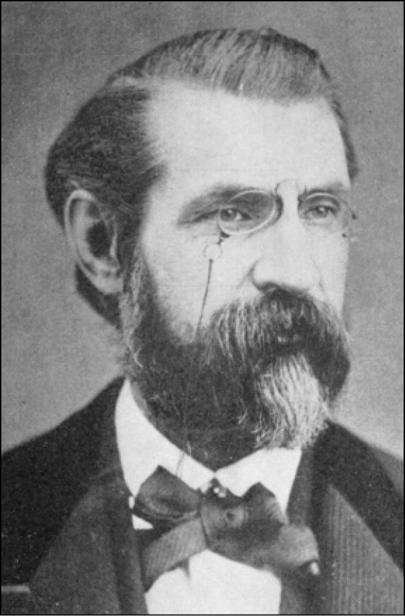

A. Oakey Hall.

In November 1868, after John Hoffman’s election as New York’s new governor had left the mayor’s office vacant, Tammany decided to nominate “the strongest man in our organization,” as Peter Sweeny put it.

6

Sam Tilden’s Manhattan Club crowd had raised its own challenger—John Kelly, the former sheriff and Tammany Sachem—but Kelly withdrew late in the race for health reasons.

7

Oakey Hall, facing a Republican, won 75,054 votes out of some 96,000 cast—a whopping 80 percent.

“It will be refreshing to have for Mayor of New York a strictly upright, honorable, capable man, and at the same time one who writes drama or a farce with equal success, acts a part as well as most professionals on the stage, conducts the most difficult cases on the calendar, sings a good song, composes poetry by the yard, makes an effective stump speech, responds to a toast with remarkable eloquence and taste, mixes a lobster salad as well as Delmonico’s head cook, smokes the best cigar in New York, respects old age, and admires youth, as poets and orators invariably do,”

8

the

New York Herald

pronounced shortly after the election—words Hall probably wrote himself, having long ago charmed

Herald

publisher James Gordon Bennett, Jr. Said the

Herald

of the mayor: “He calls a spade a spade and Horace Greeley a humbug.”

9

Tweed, the hard-nosed pragmatist, grumbled at “lightheaded” Oakey Hall. “Hall’s all right,” he once said of the mayor, “all he needs is ballast. Politics are too deep for him. They are for me and I can wade long after Oakey had to float.”

10

But Tweed recognized in Hall the perfect public face for his machine. Oakey Hall stood for progress. In an April letter to the newspapers that year, he ridiculed the backward, chaotic “old” New York, “a Metropolis without … boulevards, and without museums, lyceums, free libraries and zoological gardens” cherished by “some rich old men who cannot realize that New York is no longer a series of straggling villages” along Manhattan Island.

F

OOTNOTE

11

He pushed to pave sidewalks with Nicolson concrete instead of the traditional wooden planks or dirt, despite complaints over the $5 per square yard cost, and drew a line with city aldermen “not to give approval to schemes for wooden pavement unless property-holders in rather quiet side streets should petition for them.”

12

Hall became ubiquitous, attending public events at the drop of a hat, from the dedication of a new statue of railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt to every sort of funeral, even of political enemies like ex-Mayor James Harper and

New-York Times

founder Henry Raymond. Manton Marble’s

New York World

called him “our eccentric but talented Mayor” who “says and writes more bright things and commits more stupid blunders than any politicians we know of.” During a quarrel over how to treat loose animals causing havoc in New York’s muddy, clogged streets, another local paper quipped:

“Mayor Hall does not intend incurring even the displeasure of the dogs.”

13

Tweed, too, increasingly enjoyed the public display in this new era: As Tammany’s Grand Sachem, he now presided over the club’s arcane rituals with pomp and ceremony. At Tammany’s annual July 4 gala that year, he led the traditional grand procession draping his large body in “glittering regalia and bearing a silver war hatchet, the Tammany saint’s symbol in his hand,” as one reporter described it. His Indians and Sachems, themselves decked out in colored shoulder sashes and gold medals, followed in double file. He led the crowd in booming cheers as he mounted the podium wearing a silly-looking red, white and blue “liberty cap” and holding a staff.

14

Tweed loved costumes. At his Americus Club lodge on Greenwich’s Indian Harbor where his Tammany friends flocked on summer weekends, he enforced a strict dress code: blue cloth navy pantaloons with gold cord down the seams; blue sack coat of the navy cut; white cloth vest cut low, and navy cap.

15

In January, he led the dancers at the club’s annual ball at the Academy of Music.

His political events, too, became carnivals. That August, he called a mass meeting to protest American inaction against British oppression in Ireland and Spanish oppression in Cuba. Thousands of immigrants came pouring out of slum neighborhoods to flood Tammany Hall and fill Union Square with picnic lunches and pails of beer. A green Irish flag waved over a wooden stage and sounds of fiddles and tin whistles filled the air with songs like “

Garry Owen

” and “

Patrick’s Day

.” Tweed greeted them and blushed at the applause, but as usual handed off the speech-making to “our worthy mayor” Oakey Hall who happily entertained the crowd. Shouting out his speech from the platform, he mocked President Grant for lounging in his “smoking room” as “the American eagle sits supinely in the White House and smokes cigars.” When a voice in the crowd shouted back “The General is looking for a crown,” Oakey Hall stopped his speech, paused a moment, then observed: “Ah, as they say in the streets of London, the smallest change for a sovereign is half a crown”—winning a round of laughs.

16

In August, Tweed invited a boatload of charity children—260 teenage boys from pauper schools on Hart and Randall Islands—to spend a sunny afternoon on his forty-acre Greenwich, Connecticut estate, Tweed’s “country seat” as some called it. He sent a band, the “Tweed Blues,” to welcome the boys arriving by boat at the Americus Club pier at Indian Harbor and then greeted them at his home, standing side-by-side with his 18-year-old daughter Josephine. After a few speeches, he served them a banquet under what reporters called a “spacious circular pavilion” erected on the wide green lawns, though the charity boys had to fight for food with the swarm of news reporters Tweed had invited to witness his good deed. “I never saw so many persons claiming to represent the newspaper profession,” one of them wrote.

17

These were gravy days. Tweed had grown rich, and bolder in showing it. He held court each morning at his Duane Street office, dispensing liquor, cigars, and favors amid the elegant finery of mahogany furniture, cut flowers, and glass dividers. Passersby described his new home on Fifth Avenue at 43rd Street as “a palatial mansion, with a brownstone front, an aristocratic flight of stone steps, and a front door buried in gorgeous moldings and carvings of mahogany and rosewood.” Inside, Tweed served champagne and dollar cigars in “rich parlors [kept] warm with luxurious gaslights, which danced within their figured shades.”

18

He rode about town in a barouche carriage with a four-horse team and traveled the state’s rail lines in a private Wagner parlor car, playing fifty-cent-ante draw poker with political friends along the way. At the train stations, he avoided pesky job seekers and favor-askers by using his own private entrance.