Brain Over Binge (14 page)

Authors: Kathryn Hansen

19

: Why Did I Continue Having Urges to Binge?

Reason 1: Persistence of Survival Instincts

I

f I binged for the first time because dieting triggered my survival instincts and caused my first urges to binge, that still didn't explain why I kept binge eating for six years. If my animal brain drove me to binge to compensate for my dieting and protect my body against future dieting, then wouldn't one binge have been enough? Why did I repeat such a disgusting behavior again and again? Why did my brain keep sending out those relentless urges week after week, month after month, and year after year?

There are two reasons for this, one I'll discuss in this chapter and one I'll discuss in the next. The first is the same reason I began having urges to binge in the first place: survival instincts.

My survival instincts didn't just turn off after my first binge, especially because after that first binge, I continued my restrictive eating habits and tried to control my appetite even more. I didn't just sit back and accept the binge—no one who ends up bulimic accepts their binges—but instead, I tried to rectify the situation. Understandably, I was worried about gaining weight; so I chose to eat very little for the rest of the day and run six miles in an attempt to undo the damage.

In other words, I followed my first binge with my first purge. It wasn't a drastic purge, like self-induced vomiting or taking laxatives, but it was a purge nonetheless. My purge temporarily made me feel better about having binged because I felt I had avoided gaining weight. However, my purge sent a dangerous message to my animal brain—the message that I was still depriving my body of food. My purge only served to keep my survival instincts in full force and fueled my animal brain's natural drive to protect my body from starvation.

By restricting food and running so much after my binge, I effectively created another artificial food shortage, and my animal brain—more specifically, my hypothalamus—sensed I was starving again. I had essentially proved to my animal brain that binge eating was necessary and vital to my survival. Even though my purge temporarily made me feel better about myself, it made my animal brain even more determined to defend against future starvation so that, by the time I sat down to dinner the night, my survival instincts were already in overdrive, working to make me binge again.

I didn't understand why my appetite was as strong as it was before my first binge, perhaps even stronger. I didn't understand why I still craved large amounts of food even after eating so much cereal that morning. At the time, I thought it was just because I was weak or my appetite was insatiable. I disparaged myself for not being able to control my appetite, not realizing that it was only natural and healthy for my brain to react this way.

Furthermore, after I purged for the first time, I certainly didn't begin eating a normal, sufficient diet. When the dust settled after my first purge, I went right back to restricting food. My binge seemed to prove once and for all that I couldn't be trusted around food, which made me more determined to control myself around it. I resolved to get back on track and keep a tight harness on my appetite, which only served to strengthen my survival instincts and create more urges to binge.

After I had already binged once, I had another powerful enticement to binge again: my memory. Although my first binge made me feel guilty and fat and out of control, I couldn't deny that it felt good to let go of restraint, give in to my cravings, and finally be full. I found it much easier to remember how pleasurable it had felt than remember the negative feelings. This selective memory also made sense in terms of my brain, as humans tend to remember pleasure more than pain. Further, feeding and memory are closely related in the brain. Certain neuropeptides (chains of amino acids in the nervous system that neurons use to communicate with one another), notably neuropeptide Y and peptide YY, that stimulate eating also stimulate memory, learning, reinforcement, and reward.

82

My enhanced memories of the rewarding aspect of binge eating provided me the temptation and motivation to binge again.

My animal brain generated emotions and intense feelings despite my better judgment, so that no matter how much I tried to talk myself out of wanting to binge, I wanted to nonetheless. The animal brain and survival drives don't listen to reason. My animal brain was not my enemy—it only encouraged me to binge because it sensed I needed to binge in order to survive. It was effective, because I certainly did binge again, only two weeks after the first time.

Just like the first, my second binge was unsettling but pleasurable; and just like the first time, I felt awful afterward. Riddled with the same guilt and fear of gaining weight, I purged for the second time, eating very little on the following day and running to compensate. Once again, my survival instincts kicked in and I began experiencing urges to binge and pleasurable memories of binge eating. Again, I tried to fight and reason with my cravings, but it wasn't long before I binged yet again. This cycle of binge eating and restricting/overexercising began repeating over and over.

While caught up in this cycle, it was very difficult for me to see what was happening. All I knew was that I couldn't get a handle on my appetite; the more I tried to control it, the stronger it became. I knew that my purging behaviors weren't healthy and were probably only making the problem worse, but I couldn't just sit back and do nothing after a binge. In therapy years later, I was told that my purging behaviors were only another symptom of my disorder. I learned that restricting/overexecising after binges were just other ways of attempting to cope with problems or avoid certain emotions. There was even a more disturbing theory: that I was purposefully inflicting harm on myself because of self-hatred.

After my recovery, I realized that those theories were untrue. My purging behaviors were in no way a sign of disease. It only made sense that I would try to do something to make up for my binge. My purging was actually a rational attempt to undo the perceived damage of binge eating and quell my fears of weight gain, and the purging was initiated by the higher functions of my brain. I'm not saying that exercising to exhaustion and restricting food (or, in the cases of other bulimics, inducing vomiting or taking laxatives) was intelligent; but it

was

a conscious choice. I felt out of control during a binge, so once I got control back, I had to do something about it.

Throughout my years of binge eating, it was obvious to me that my urges to binge were inconsistent with my true self—the person I believed myself to be in the present and the one I wanted myself to be in the future. My urges felt intrusive, often arriving when I least expected them and taking over my mind and body like a thief, driving me to do something I knew I'd regret. My true self felt powerless to resist; but there was one thing I could do, and that was purge—usually in a fit of desperation and shame. Purging seemingly took away the biggest consequence of binge eating: weight gain. Purging was like a safety net, and it brought me comfort to know that I could just starve myself and exercise a lot the next day, and all would be "OK." Each purge, however, only compounded my problem.

I was never successful at making myself throw up, but I can imagine the relief that some binge eaters feel when they discover self-induced vomiting. Through my years of binge eating, I felt that if I could only make myself throw up, life would be so much easier. Vomiting, I thought, would be so much less time-consuming than overexercising—albeit disgusting and painful. I can imagine that self-induced vomiting only encourages more binge eating because the effect is so instantaneous, bringing immediate rectification for the binge and instant relief from worry about weight gain. For this reason, I am thankful every day that I could never make myself throw up, because I'm sure I would have binged much more, and maybe I wouldn't even be alive today to write this book.

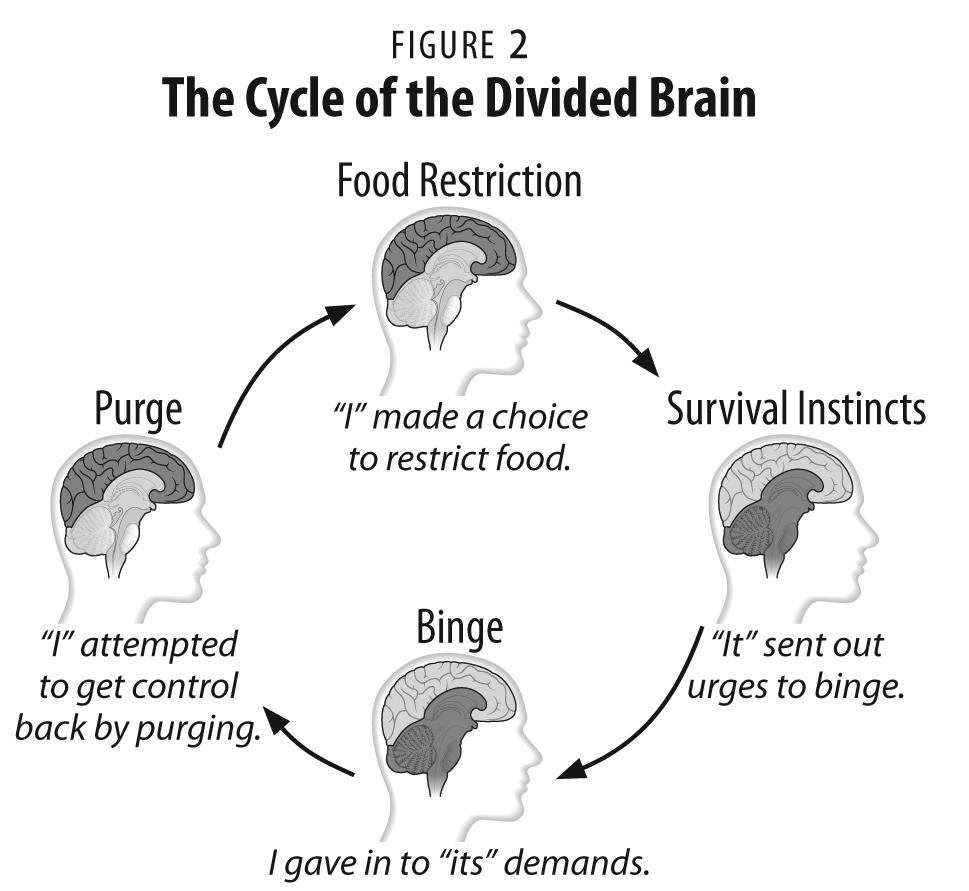

Regardless of the method of purging, the binge-purge cycle can be relentless. I have termed this the "cycle of the divided brain," illustrated in

Figure 2

below. The cycle of the divided brain is the cycle of "I" versus "it." These aren't just symbolic concepts—they are real, physical parts of the brain. "I" is the human brain, and "it" is the animal brain—more specifically, the hypothalamus. As I'll discuss in the next chapter, "it" can change as bulimia progresses and survival instincts become less of a factor, but "it" is always separate from "I"—the human brain.

There is nothing diseased about the binge-purge cycle. Yes, it is a terrible cycle to be caught up in, but it's completely natural when viewed in light of the brain. However, when this cycle is not properly understood, it can seem impossible to break.

This cycle was in place during roughly the first eight to ten months of my binge eating, but eventually, I stopped dieting.

SURVIVAL INSTINCTS DON'T LET UP EASILY

By the end of my freshman year of college, I was eating a sufficient number of calories in my normal diet, and I'd stopped cutting calories on the days after binges. During that year, I gained back all the weight I'd lost by dieting, about 30 pounds; I was no longer underweight. I did continue one form of purging, however—exercising for hours on end to make up for the binges.

I didn't understand why my urges to binge persisted in spite of my weight gain and in spite of eating enough. The answer I learned in therapy was that if I binged despite eating a sufficient number of calories, I must be binge eating for emotional reasons. In reality, this was just not the case. I was, in fact, still following my survival instincts. It was perfectly normal that I kept having urges to binge even after I stopped starving myself, because survival instincts are extremely persistent.

My fervent dieting and anorexia had made my animal brain more defensive, so that it drove me to gain more and more weight to guard against future starvation. Simply stopping the diet wasn't enough, because I had already taught my animal brain that food shortages were common. It learned to take necessary precautions by urging me to store up food and fat.

This human pattern I experienced is supported by some studies of animal behavior. Even though human behavior is more complex than animal behavior, the human brain is more similar to an animal brain than it is different.

83

Studies of rats have shown behavior similar to that of long-term bulimics; they keep binge eating even after a food shortage has passed.

84

Food deprivation changes the brain of a rat just as it changes the human animal brain, by putting it on heightened alert and causing it to seek out more and more food to protect the body from future starvation. One experiment found that rats, subjected to restrictive feeding schedules that reduced their body weight, later showed an increase in eating that continued even after they were no longer food-deprived—even after they had gained back the weight they had lost.

85

In other words, the rats continued to overeat long after it was physically necessary for them to do so.

Another study found similar results when rats were subjected to severe food deprivation for four days. Once a normal diet was reintroduced, the deprived rats ate more than the nondeprived rats even after they returned to their normal weight.

86

These two studies are not the only ones that explain how survival instincts drive overeating long after food deprivation. There have also been human studies showing that food-deprived individuals will remain preoccupied with food and overeat even after the threat of starvation has passed—for example, in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

87

In the rat studies, the deprived animals binged on highly palatable foods—tasty, sweet foods such as sweetened milk, Oreo cookies, and sugary cereal—not on their standard bland diet.

88

Sweet foods are the most palatable, the most pleasurable; additionally, foods high in sugar and fat are dense with calories, making them attractive to the food-deprived and adaptive for survival. In fact, "Like a history of caloric restriction, the presence of HP [highly palatable] food also appears critical to binge eating,"

89

and access to highly palatable food is necessary for continued binge eating.

90