Brain Trust (7 page)

Authors: Garth Sundem

This is why you need to turn across the wave. Turn now. Turn before it’s too late. The best surfers seem to catch waves having already started their cut across its face. Intermediate or big-wave surfers make a turn near the wave’s base and cut back into it. Beginning surfers become intimate with salt water.

But in addition to staying afloat, there’s another neat thing about the turn: It allows you to accelerate to faster than wave speed (if you’re into that sort of thing). At the bottom of a turn, you push not only against the force of gravity, but against the centripetal force of the turn itself (see this book’s entry describing how to take a corner). If you’re crouching down at the bottom of the turn and then stand while turning, the energy of your legs

pushes against this centripetal force like a skateboarder on a half-pipe, pumping energy into the system, which, in this case, makes you go faster.

And now, rocketing around the wave in arcs and slashes, you have but one task left: hanging ten, or intentionally shifting your center of gravity as far forward as the board allows in order to hang your toes off its front edge in a move that is just as awesome as it is suicidal. Surely holding this position defies the laws of physics?

Doherty points out that the key to hanging ten is not what happens at the (suicidal) front of the board, but what happens at the back. If a surfer is hanging ten, you can be sure the board’s tail is no longer buoyant on the surface of the wave. Instead, it’s shoved back into the breaking wave like a pry bar under a heavy object, counterbalancing the weight of the surfer up front. This is one reason hanging ten is a move reserved for longboarders—you need a lengthy pry bar for leverage.

Read. Visualize. Learn. As for me, I moved to Colorado.

A quick search for Paul Doherty finds his

Exploratorium homepage, where he describes about 250 very cool hands-on science experiments, including how to make a lava lamp and how to ollie a skateboard.

I would maybe have surfed more if it weren’t

for a 2010 article in the

Santa Barbara Independent

describing a kayaker in the Channel whose boat was mouthed by a great white shark. But what if my board could protect me from sharks? A surfboard patent application by inventor Guerry Grune describes its included locator device and alarm, alerting the user to “large aquatic animals” as well as a “signal generator configured for transmitting interference signals to disrupt the electrosensory perception system of the aquatic animals.” That, truly, is awesome.

Using an idea imported from Switzerland (where else?), Chicago and New York invited local artists to decorate fiberglass cows. For a set display period, these cows graced city public areas, after which the bovine couture was auctioned, with the proceeds going to charity. Toronto did moose. Boston did cod. St. Paul did Snoopys.

In addition to stuffing cash in city coffers and (presumably) providing mad backyard kitsch for winning bidders, the Cow Parade program created huge amounts of auction data. How do you sell a painted version of a city’s iconic animal for the biggest possible bucks? You put bidders in a live setting, ratchet up the time pressure, and create competition. The more emotional arousal you can create in bidders, the higher the eventual selling price. Simply, when people lose their heads, they reach for their wallets.

Gillian Ku, assistant professor of organizational behavior at the

London Business School, wondered if the same would be true on eBay. She got data from (where else?) cows. Specifically, from an eBay seller with the screen name Browncow, who was selling Tommy Bahama shirts. “He was manipulating whether shirts had straightforward descriptions or puffed descriptions,” says Ku—you know, descriptions that promise the most amazing shirt ever that hot strangers will want to rip from your body!!!! That’s puffery. And it helped sell Tommy Bahama shirts.

But only if a couple other things were true too. One of these factors was starting price. And here’s where it starts to get interesting.

Gillian Ku found that eBay starting prices throw conventional economics on its ear. “It should be all about anchoring,” she says—meaning that a high starting price should signal an item’s worth and lead to a higher selling price. This is what Steve Jobs did when he anchored the price of an iPhone at $599, making the on-sale price of $299 look like a steal. “But what we found on eBay is that low starting prices, not high prices, led to a higher selling price.”

But (again), only if a couple other things were true too.

If an auction was misspelled, a higher starting price provided the anchor that economics expects—higher starting price equals higher ending price. And having a reserve price nixed the effect of a low start.

And by this time, Ku started to see a pattern: “It’s all about traffic,” she says. A low starting price decreases barriers to entry. Having more entrants increases the chances of hooking a serious one. And even bidders who didn’t mean to be serious can get sucked into an escalation of commitment by investing time in bidding and rebidding while the price is still low. And finally, high auction traffic in the form of page views and number of bids is another way to signal value—certainly it has high worth because,

well, look at all the people who’ve been here! (It’s like evaluating a book’s worth based on its number of online reviews—hint, hint.)

Let’s be clear: With little traffic, it’s best to anchor expectations to a high starting price and list the item in an accurate, businesslike way. If you’re going to doom yourself to pitiful traffic by misspelling your item, you’d better hope someone clicks buy it now. Same if you’re listing an item that’s so niche, it’s inconceivable that many people would give it a look. But if you’ve got a shot at an auction with more widespread appeal, create traffic with a low starting price, no reserve, and high puffery. This is the competitive arousal model. In cities it created spotted-cow fever, and on eBay it means higher selling prices.

Ku and co found the opposite to be true of

negotiations: A high starting price for a firm up for acquisition, salary negotiation, or asking price of a used car leads to a higher final agreement price. The essential difference is the number of possible bidders—in a negotiation, you’re only going to have a few buyers, so your best bet is to anchor expectations to a high opening price.

Being a music prodigy would be totally awesome because it would nix the need to converse, cook, flirt, provide, smolder, or otherwise prove your sexiness—you could simply strum your way into your mate’s heart.

While studies have shown that becoming a virtuoso is similar to learning a trade—ten years including ten thousand hours of practice seems to do the trick—there’s a shortcut to musical maestrosity, allowing you to spend the saved time snogging: Simply be born with perfect pitch, the seemingly innate ability to hear a note and name it. Once you truly hear music, externalizing it through an instrument is as simple as learning to type (mostly …).

But if you had perfect pitch, you’d know it, if for no other reason than people whistling in the airport would sound physically, painfully, out of tune. (This according to my friend Ariel, who was an orchestral recorder prodigy before switching to heavy-metal guitar in college and environmental architecture after.) And until recently, experts thought that that was it—at birth, you can hold a note in your mind’s ear or you can’t. If you’re born without the gift, the theory went, your only hope is the consolation prize of painstakingly training relative pitch. For example, learning that the “way up high” leap in “Over the Rainbow” is the interval of a major sixth, as is the iconic leap in the Miles Davis tune “All Blues.” Likewise, the first interval in “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” is a perfect fifth. And based on learning these leaps, you can learn to deduce any note on the keyboard given a starting point. In university music programs around the world, a teacher plunks a note, names it, then plunks another note, and students who have successfully trained their relative pitch can name the second note.

But what about naming the first note? What about perfect pitch? What about that shortcut to limitless snogging?

Diana Deutsch, UCSD prof and president of the Society for Music Perception and Cognition, thinks perfect pitch can be trained—but only if you start early.

In part, she bases this opinion on an illusion.

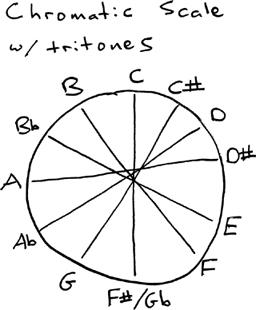

In music, a tritone describes the interval that splits an octave exactly in half. For example, C and F# form the interval of a tritone, and so do the notes D and G#. The interval was banned during the Inquisition as the

diabolus in musica

(the devil in music). Today it starts

The Simpsons

and makes Danny Elfman scores of Tim Burton movies immediately recognizable. Now imagine alternating C and F#, like the siren on a British ambulance. Really, you wouldn’t know if the pattern is ascending (C–F#, repeat) or descending (F#–C, repeat).

But here’s the thing: You do know. Every note has a companion that’s exactly half an octave away, and depending on which tritone is played, you perceive the interval as either descending or ascending. And you don’t ever switch. It’s fixed. Deutsch discovered this tritone paradox and calls it “an implicit form of perfect pitch.” Somehow, some way, we all fix notes and hold them in our minds.

So why doesn’t the universal ability to hold abstract pitches allow us all to know note names when we hear them? Why—dammit—can’t we all be prodigies!

Deutsch found that fixed pitch does, in fact, allow perfect pitch … but only in certain cultures.

Sure, an individual American’s perception of the tritone paradox is fixed—maybe you hear C–F#–C–F# as an ascending pattern—

but as a culture, Americans may each hear tritones differently. Your friend Barb may hear C–F#–C–F# as a descending pattern. But here’s the interesting bit: In Vietnam, the vast majority of the population hears tritone paradoxes in the same way—they’re fixed not only on an individual, but on a cultural level.

Blame it on language, says Deutsch. In Vietnamese and other tonal languages, a high “ma” can mean something very different than a low “ma,” and so infants learn very early to pair fixed tones with fixed meanings. Later, it’s easy to use this same brain mechanism to pair tones with note names like A, B, and C. Deutsch explored data from the Singapore Conservatory and other Asian music schools, and found that—sure enough—the incidence of perfect pitch is much higher in speakers of tonal languages.

Deutsch thinks it might be possible to create a similar mechanism in English speakers. “If your son or daughter has a keyboard at home, use stickers to label the notes with whatever symbols they understand first.” If your child recognizes barnyard animals or pictures of family members or colors before he or she recognizes letters, label the keyboard with animal, family, or color stickers. (All G’s get a cow, all F’s get a pig, etc.) This encourages your budding Beethoven to pair tone with meaning—any meaning works!—which you can then switch to note names once your child knows his or her letters.

It’s too late for you—“It seems as if the window for creating this pairing is closed by about age four,” says Deutsch—but perhaps early action can allow your progeny to be prodigy.