Breaking News: An Autozombiography (3 page)

‘

Neil, where are you?’ Lou was shouting. ‘I’ve been waiting ages. No I haven’t. No, well thanks a lot. Thank you very much.’

‘

Lou?’

‘

Neil’s gone,’ she explained. ‘He’s already in his car on his way back down to the coast. Cock. The trains aren’t running either. Look, I drew nine pm as my slot to leave, so that gives me plenty of time to find an alternative. Someone’s got to look after Clive anyway. I’m staying here.’

‘

No no no. Absolutely not. No way. Who’s Clive, and what floor are you on?’ I didn’t like it when she sounded so determined.

‘

Floor six, but I’m staying here.’

‘

Yeah, and I’m a lady chimp’s chuff. We’re coming to get you.’ I cleared my throat and put on my best American accent. ‘When we get there, don’t make me come looking for you.’ I waited for an answer, but the phone was dead.

‘

Dawn of the Dead

?’ Al asked me as he sat back down. The old man was still outside.

‘

Well spotted sir. Have you got reception on your mobile?’ I asked him.

‘“

No Network Coverage”,’ he read. ‘That happened on the millennium, do you remember? The system got jammed up by every twat in the country texting ‘Happy New Year’, or ‘HPY2K’ or whatever.’

‘

Well what were you doing to know that then? Texting someone?’ I asked, trying to hide some light smugness.

‘

Fair point, smartarse’, he said as I checked the landline – also dead. Not static but deathly silence, as if it had been unplugged.

‘

Look chum, we’ve got to go. Lou’s car’s been nicked.’ I said simply. Al pointed over his shoulder towards the window.

‘

Mine’s still there,’ he countered.

‘

I know you dippy stoner, and we’ve got to get in it and go now! Come on!’ I made wafting hands at him.

‘

Alright, we’re going now,’ he said, leaping off his chair. ‘Look at you there, holding me up. Fuck’s sakes,’ he grabbed his car keys, rolling tin and tobacco and headed for the door, as a scream rang out from down the road. I was already breaking out in a sweat from the summer heat, but that sound chilled me to the bone.

‘

Let’s go.’

Breaking Out

[day 0001]

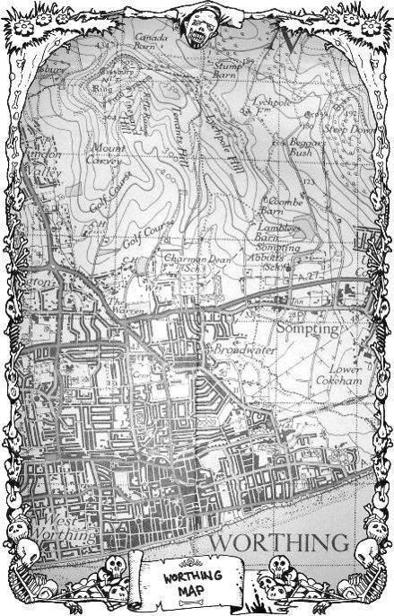

Lou and I lived in a terraced house in a fairly unremarkable seaside town in the south of England, but she worked in her office in Crawley thirty-odd miles up the road to London. If you drove east from our house along the coast road you’d soon get to Brighton, where Al ran his painfully hip clothes shop. His car was a battered old Audi four-wheel-drive estate with a crumpled bonnet and a dog grille in the boot for Dmitri, his two-year old beagle and Floyd’s uncle. It was parked ten doors down the road; his dog was with his shop assistant in Brighton.

Floyd slipped through my grasp and out of the front door. I threw his lead out to Al, went back through the kitchen to lock the back door, picked up my useless mobile phone, put my keys down on the coffee table, then slammed the front door shut and joined Al on my driveway. The wall of midsummer heat stole the breath from my lungs, and I squinted at the cloudless sky through my fingers.

‘

Hot.’

‘

Look,’ Al was pointing. ‘He’s been sick. Dirty boy.’ The old man in his cord dressing gown and slippers was still staring towards us. Other than him, the street was empty. Mock-Tudor toy-town terraces.

‘

It must have been that silly cow screaming.

Jeremy Kyle

must have riled them up.’ I ventured hopefully, looking up the road.

‘

He’s been sick,’ Al repeated. The old man had a beard of vomit.

‘

Should we do something?’ I asked, not really wanting to do anything.

Floyd’s body was arched backwards, snout skywards, and he was drooling; his nostrils pulsed like they had a little heartbeat of their own. I couldn’t smell anything except the heady, slow burn of a summer that had long outstayed its welcome. Hot tarmac and rubbish. Al had an unflappable belief that Dmitri wouldn’t ever run off, and assumed the same of my dog even though he was still a young pup and therefore a foolhardy twit. He hadn’t been wrong though - until that point.

Floyd bounded into the mercifully empty road, tail wagging furiously and his long ears following his head half a second later. He laid down three or four feet away from the huddled figure, whining quietly, before standing again and ducking his head, doing the half-bark, half-howl thing that beagles do. The pale old man, his jaws gurning like a camel, slowly turned to look at my dog. Floyd backed up a few paces, as his youthful baying turned into a deep growl I’d never heard from him before. I walked into the road.

‘

Come on boy,’ I clicked my fingers. It was like a trigger.

Floyd kicked away at the asphalt with his lanky legs and propelled himself at the old man’s face. His lunge only just fell short, instead snapping up a mouthful of soiled dressing gown lapel and bringing the pensioner crunching to the ground beside him.

‘

Fuck. Floyd, heel! You alright mate? Heel!’

Instead of heeling, Floyd started tugging at the old man’s lank comb-over, spinning him on his side in a slow-motion geriatric breakdance. I grabbed a healthy handful of puppy fat and hauled him off, but he had a good grip and came away with the old man’s remaining hair. I slapped his arse and he sat, chewing and looking pleased with his handiwork.

‘

I’m so sorry, mate. Here,’ I held a hand out, which he ignored. He rolled onto his front and awkwardly hauled himself to his feet as Al walked over to join me.

‘

Is he alright?’ Al asked.

‘

No idea,’ I said out of the corner of my mouth. ‘I think he’s shat himself though, he stinks.’

‘

Maybe he’s got ‘flu,’ Al laughed. Floyd started growling again but he was still chewing hair so the growl quickly turned into a hacking gag. I pulled some strands out of his mouth and rubbed his chest. The old boy slowly turned to face us again. ‘Look, I’m really sorry - he’s never done that before. He’s a pup,’ I explained. Illogically, I offered the man his hair back, but Al put my arm down.

‘

He doesn’t want that now,’ Al was backing up. ‘That’s not vomit chum.’

His stringy umber beard of sick glistened red in the bright sunlight. Instinctively I backed up too.

‘

Should we do something?’ I said again, even less keen now he looked like he might be infectious instead of just ancient.

‘

No. That copper said to help relatives and neighbours.’ Al said quietly.

‘

Well, he is a neighbour.’

‘

Not a next-door neighbour. He’s over the road from you, and up a few. Let’s go.’

I didn’t need any persuading, and the old man seemed pretty much okay all things considered. I pulled the dog by his collar, claws scrabbling on the road. His attention span was ridiculous, and as soon as he saw Al open the boot he jumped in eagerly, the floor scattered with the rubber bone toys of his uncle Dmitri. I shut him in and joined Al in the front. I swear he had lowered his car seats somehow, making it feel like we were in a Los Angeles low-rider with baby nines under the seat and a couple of ho’s in the back. But we were in a beaten-up Audi with no weapons whatsoever, and my wife was stuck in Crawley. Al performed his pre-flight checks – ignition on; CD in; doobie out from behind ear; pull away. Then maybe mirrors, but rarely signal. I looked back at the old man standing in the same spot like nothing had happened.

‘

He’s giving you the evil eye,’ Al chortled.

My street was quiet even though it led straight out onto the main road to Brighton. It was narrow and curved in the middle, and had never become a rat-run for the school-run or a detour for the rush-hour even though it did cut out some traffic lights. We didn’t have to wait long at the T-junction, which on any other day took forty or fifty cars before someone let you out, or you got the chance to plunge headlong into a gap. That day, even though it was much busier than usual, we were waved out almost straight away. That great English characteristic of ‘crisis-politeness’ came to the fore even though I’d have bet a decade ago before that it had long since vanished. The traffic ebbed and flowed as we headed east, but remained fairly good-natured. The on-ramps were swollen, but almost everyone waved people out in front of them, even Al, but as a result we often ground to a halt. I wondered how long the mass courteousness would last as Al flicked over to the radio, to an advert literally singing the praises of a local carpet warehouse in mock Gregorian chant.

‘

Put Radio 4 on,’ I suggested earnestly. After a bit of prodding, the sounds of

The World at One

poured forth. I always listened to Radio 4 in my workshop, even though it was often a toss-up between bladder phone-ins and documentaries about moss. It was good because music - even music I loved like The Who and Led Zeppelin - didn’t help me to work, unlike almost everyone else it seemed. After a few months of working for myself I realised I couldn’t get anything done without

Woman’s Hour

to start my day. I was hooked.

Al pushed his antique Aviator sunglasses onto his forehead and reached into the glove box, pulling out his St. Andrews enamel Zippo. I had a St. George Cross on mine and my mate Vaughan had a Welsh dragon. Jay had bought them for us all as Christmas presents over the past few years. Lou organised a ‘secret Santa’ thing so we didn’t all have to buy half a dozen presents each, although only Lou would have bought anyone anything anyway. We would pick a name from a hat, returning the slip of paper if we drew our own names or if we’d had that person last Christmas. Then you bought them a present under £20. Jay had completed the Zippo set with my one last year, and had almost pissed himself with excitement.

‘

You can be Angliax’, Jay had giggled to me. ‘Al’s Doctor Scotland, and Vaughan’s Captain Taff. I’m basically your leader’, he had explained, almost certainly disappointed he’d not got a flag on his lighter. ‘You’re all my super-bitches,’ he had explained.

Al pulled on his doobie and we listened; there was some good news – no mass graves or funeral pyres were planned, and family burial plots would not be commandeered. They read out a list of public parks and ‘green spaces’ where ‘crisis management spokes’ had already been set up, and additional medical help or advice could be sought at temporary ‘community care nodes’. The health minister wasn’t available to comment on the fact that there were already no hospital beds available, but had clearly left her mark on the day’s jargon. It had become impossible even for the hospitals to remain in contact with each other as they became overwhelmed. Looting had been reported in some of the major cities but martial law was, apparently, a long way off. This wasn’t as reassuring as I’m sure they had hoped it would sound. Apparently the situation in the hospitals had been further exacerbated by a marked increase in road traffic accidents, and it wasn’t long before we saw one of our own.

The staccato rhythm had eased into a flow as the A27 moved further from the suburbs and we began to pick up speed. Al was doing something which annoys me when others do it; weaving in and out of the lanes, filling gaps by undertaking other cars. I said nothing as I was anxious to meet up with Lou, and kept forcing from my mind the thought that we might well get stranded in Crawley. Al seemed oblivious to everything except the traffic – he might as well have been holding a PlayStation controller. Trance-like, he picked his way from one side of the dual carriageway to the other towards the Southwick Hill Tunnel which cut into the slow curve of the hill up ahead. The rapeseed fields on either side of us blazed yellow, and I closed my eyes against the beating sun. I had one of those forgotten glimpses of childhood complete with sounds and smells – of the fields above Lancing burning, spitting black clouds into a blue summer sky. Stubble burning was a practice that hadn’t happened in years, a cheap way to ready the harvested fields for the next year.

The sound of our tyres squealing shook me out of my daze. My hands lunged for the dash and my legs went taught, lifting me a few inches off my seat as a red Fiesta two cars in front of us veered across the road. I thought for a second or two that someone had got pissed off with Al’s driving, and was blocking us off. So did Al, who was instantly apologetic.

‘

Sorry dude!’ he waved and flashed his lights. He turned to me. ‘I’m still tuned into the PlayStation,’ he explained. He’s one of the good ones, my mate Al – he only wants to go calmly through life, not ruffling feathers or rocking the boat. I knew there wasn’t any meanness in the way Al was driving that day - he had learnt to drive on the eight-lane behemoth highways of Los Angeles, when he was out there playing college basketball. They don’t do indicating there, or steering for that matter; light collisions get waved on and it is your duty to drive for your life. Such skills proved useful that day.