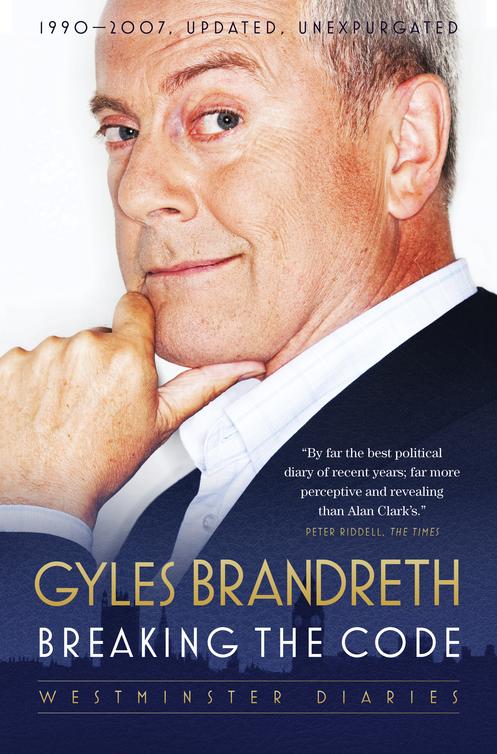

Breaking the Code

Authors: Gyles Brandreth

PRAISE FOR

BREAKING THE CODE

‘Searingly honest, wildly indiscreet, and incredibly funny …

Breaking the Code

is the best book I’ve read this year.’

LYNDA LEE-POTTER,

DAILY MAIL

‘Brandreth is the true Samuel Pepys of our day.’

ANDREW NEIL,

BBC RADIO FIVE LIVE

‘Brandreth, for my money, offers about the most honest, and the most amusing, account of the demented, beery futility of the Tory-ruled Commons in the 1990s.’

BORIS JOHNSON,

DAILY TELEGRAPH

‘Hilariously acute … Portraits withering in their accuracy … Irresistible.’

MATTHEW D’ANCONA,

SUNDAY TELEGRAPH

‘One of the most attractive things about these diaries is that the diarist is (like Alan Clark) one of those who can admit, even to himself, to having human weaknesses … Extremely touching … Brandreth emerges as a decent, amusing, talented and charming man.’

SIMON HEFFER,

DAILY MAIL

‘The sheer madness of Westminster is perfectly reproduced.’

IAN AITKEN,

THE GUARDIAN

‘As a witty and insightful chronicler Mr Brandreth is unsurpassed.’

MICHAEL SIMMONDS,

THE SPECTATOR

‘Brandreth has produced something unexpected: a political book about the Major years which makes perfect holiday reading … A fine and sympathetic writer – a good witness. His unpretentious book should stay in the repertoire for many years.’

MICHAEL HARRINGTON,

TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT

‘Lots of good raw material here for historians.’

IAN MCINTYRE,

THE TIMES

‘This book is a joy. For anyone interested in politics – indeed, for anyone

not

particularly interested in politics, but still fascinated by people – it’s a complete delight. It is funny, informative and irreverent, and, more important still, it opens a window on the Westminster world which has been tightly shut since some time in the middle of the last century … Shrewd … Perceptive … And really very, very funny.

I laughed until I almost cried … You can open the book at any page and read with relish.’

JULIA LANGDON,

GLASGOW HERALD

‘Brandreth proves to be an entertaining, indiscreet and fluent diarist.’

ALAN TAYLOR,

SCOTLAND ON SUNDAY

‘Enormously entertaining.’

SIMON EVANS,

BIRMINGHAM POST

For Michèle

who had the worst of it

and made the best of it

W

hen this book first appeared a number of good people – friends and former colleagues – viewed its publication as an act of betrayal.

On the first anniversary of the 1997 general election, when brief extracts were published in a Sunday newspaper, the Conservative Chief Whip telephoned me at home. He was a model of quietly spoken courtesy. I would have expected nothing less: James Arbuthnot, MP for North East Hampshire, is a gentleman. (Eton, Captain of School; Trinity College, Cambridge; in the expenses furore of 2009, he immediately apologised and repaid the public funds he had claimed for the cleaning of his swimming pool.) He said to me, ‘Gyles, you do know that you are breaking the whips’ code, don’t you?’

I did. And it troubled me – not because in doing so I was revealing any great state secrets, but simply because government whips do not talk about their work, do not discuss their role, do not describe the way they go about their business. They never have – or, at least, they never had until I published

Breaking the Code

.

The day after getting the Chief Whip’s call I happened to find myself at a BBC studio talking to Anthony Howard, veteran political commentator and then (perhaps appropriately, under the circumstances) obituaries editor of

The Times

.

‘I’ve got a moral dilemma with these diaries,’ I said.

‘No, you haven’t,’ said Tony. ‘You’ve got a personal dilemma. It’s not a moral issue. Government whips are government ministers, paid for by the taxpayer. What they do and how they do it are matters of legitimate public interest. If by publishing your diaries you’ll be burning your bridges, that’s a personal matter. That’s for you to decide.’

I decided to take the risk, not only for reasons of cash and vanity, not simply because I enjoy reading other people’s diaries and I hope that others may enjoy reading mine, but because I was not convinced that the secrecy surrounding the Whips’ Office – and much else that happens in Westminster and Whitehall – is either right or necessary.

In my telephone conversation with the Chief Whip he reminded me that part of the potency of the Whips’ Office derives from the mystery surrounding it. He echoed Walter Bagehot’s famous line on the monarchy: ‘We must not let in daylight upon magic.’

But Bagehot died in 1877. We are now well into the twenty-first century and whips are neither magicians nor freemasons: they are Members of Parliament with a specific job to do. Their task is to manage and secure the parliamentary business of the government of the day and, in so doing, manage and understand their fellow MPs. If they are more open about the way they operate I can see no harm in it, and, even, some good.

On the day

Breaking the Code

was published a large brown envelope was delivered to my front door. Inside it was a second envelope. Inside that was a sheet of white paper that contained nothing but a large black spot – a mark of shame. I had betrayed the Office and the Office wanted to make that fact clear to me. I was not in any doubt and so not surprised in the months that followed to find former fellow whips, when I chanced to meet them or to pass them in the street in Westminster, avoiding my eye or, in some cases, deliberately turning away and cutting me.

It is twenty years since I joined the Whips’ Office and I believe by most (if not all) of my former colleagues I have now been forgiven – or forgotten. Happily,

Breaking the Code

was well-received when it first appeared – and not only by the reviewers. Several of the leading characters in the narrative wrote to tell me that I had got it ‘about right’. The book played a part in the development of two successful plays about the workings of the Whips’ Office:

Whipping It Up

by Steve Thompson (2006) and

This House

by James Graham (2012). And in 2005, a former head of the Whips’ Office, no less, Tim Renton, Baron Renton of Mount Harry, Chief Whip during Margaret Thatcher’s final year in power, published his own account of the history and practice of parliamentary whipping.

These diaries, of course, cover more than my sojourn in the Whips’ Office. The extracts begin in May 1990, when I was deciding it was about time I got into Parliament, and end in May 1997, when the electors of Chester decided it was time I got out. Those seven years take us from the fall of Margaret Thatcher to the election of Tony Blair, and in choosing the material for publication – reducing the potential of more than a million words to one manageable volume – my aim has been to provide both an informal record of some eventful years in British politics and one individual’s account of the everyday reality of what is involved in becoming a parliamentary candidate, securing a seat, fighting an election, arriving at Westminster, and, once there, attempting to climb the greasy pole. In its way, I hope that aspect of the book is as revelatory as my account of life as a government whip.

In 1990 I was working mainly in television and publishing. I was also non-executive director of a successful company (Spear’s Games, manufacturers of Scrabble) and

deputy

chairman of a failing one (the Royal Britain exhibition at London’s Barbican). In my spare time I was actively involved in the work of the National Playing Fields Association, the national trust of recreational space. Once I became an MP I was wholly engrossed in my political life. For five years my routine hardly varied: Mondays to Thursdays I was

at Westminster, morning, noon and night. I would leave my home in Barnes, southwest London, at 7.00 a.m. and get back at midnight. On Fridays and at weekends I was mostly in my constituency. I hope I was a conscientious MP. I certainly tried to be. The diary was written in various places: in my study at home in Barnes; in bed at our flat in the centre of Chester; on trains and planes going to and from the north-west; at the House of Commons, occasionally in the Chamber itself, mostly in the Silent Room in the House of Commons Library, my favourite place in my favourite part of the Palace of Westminster. I have a wonderful wife and remarkable children. That they barely feature here reflects not only the editing process, but also the fact that the committed MP all too easily loses sight of his family.

When I was at Oxford in the late ’60s I was interviewed by the

Sun

newspaper and, if the cutting is to be believed, boldly declared that my life’s ambition was ‘to be a sort of Danny Kaye and then Home Secretary’. My plan didn’t quite work out. I became a minor-league TV presenter and a Lord Commissioner of Her Majesty’s Treasury. I have no regrets, but no illusions either. These are not a distinguished Cabinet minister’s memoirs. These are the daily jottings of a novice backbencher turned government whip. They reveal assorted weaknesses: impatience, intolerance, intemperance, vanity, egoism, faulty judgement, lack of discretion, absurd ambition (quite embarrassing at times), and a naive eagerness to please. Alarmingly, I am not sure they reveal any strengths at all – other than a keen sense of the absurd. But they are what they are, edited yes, but undoctored, presented as they were written on the day, without stylistic improvement, without benefit of hindsight.

Meeting Gordon Brown at 11 Downing Street in 1998 (he was not recruiting me to the Third Way: we were having coffee after appearing on

Frost on Sunday

) the then Chancellor of the Exchequer told me that he had enjoyed reading my account of life at the Treasury under Kenneth Clarke and Norman Lamont. ‘I was particularly fascinated by the meeting you called “prayers”,’ he said. ‘We don’t have “prayers”.’ Times change. Long-serving MPs of all parties tell me that the camaraderie and clubbability of the House of Commons that I knew in the 1990s has gone. The more civilised working hours introduced by New Labour have seen to that. And several New Labour MPs of the 1997, 2001 and 2005 intakes have told me that, having read my diaries, they marvelled at the ready and regular access backbenchers had to the most senior members of the government in John Major’s day. Throughout his time in office, Mr Major was available to parliamentarians in a way that, by every account, Messrs Blair and Brown were not.

John Major is the principal player in this story. He makes an unlikely hero: he is not ‘box office’ in the way that Margaret Thatcher was. But to me he is a hero nonetheless, and, re-reading these diaries and reflecting on his record and on the way he kept the show on the road in the most inauspicious circumstances, my admiration for him

continues to grow. He is more interesting than most people realise, and more achieving. It is not easy being Prime Minister, as Gordon Brown demonstrated.

‘A decent man dealt an unlucky hand,’ was Douglas Hurd’s assessment of Mr Major. What history’s judgement will be it is still too soon to tell. What is certain is that John Major led the Conservative Party to a remarkable victory against the odds in 1992 and led them to an historic defeat in 1997. What happened in between is what this book is about.

As a postscript, I have added some extracts from my diaries covering the years since 1997. I have included them to tie up a few loose ends and to give a flavour of ‘what happened next’, but I have kept them brief because in politics, in my experience, you are either in the game or you are out of it. For a few years I was in it and – for all the horrors I describe in the pages that follow – there is nowhere else that I would rather have been.

Gyles Brandreth

2014