Breasts (27 page)

Authors: Florence Williams

Tags: #Life science, women's studies, health, women's health, environmental science

This much, I hope, I can handle. If I’ve learned anything, it’s that cancer detection is as much art as science. BSE isn’t perfect, and it’s not going to work for everyone. But my foray into self-monitoring has convinced me that I can undertake some useful reconnaissance. As cancer survivor Hurst put it, “We’re lucky our breasts are on the outside of our bodies where it’s possible to become familiar with how they feel. We’re not talking about our lungs here.”

My best advice to you, dear reader: know thy breasts.

THE FUTURE OF BREASTS

The world is too much with us; late and soon, Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers

—WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

I

T WAS MID-AUGUST, TIME TO GET OUT OF THE LABS, TURN OFF

the computer, and head for the mountains. I had a good excuse: a fundraiser for breast cancer research. I guilted my friends into donating some money, and I promised I would try to haul myself up three fourteen-thousand-foot peaks in one day. Thankfully, they are very close together. My team included five women and one very tall man wearing an Indiana Jones hat. He would be our beacon.

We were all climbing for different reasons. Lisa and Steve were climbing in honor of her mother. Natasha and Cindy were climbing for the camaraderie and a good cause. I was climbing in memory of my grandmothers, and for my daughter, in the hope that we may learn how to prevent breast cancer in time for her. Then there was Sherrie, whose daughter, Lesley, hadn’t been so lucky. She’d recently been diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of thirty-four.

Lesley, round faced and red cheeked, bundled in a puffy down

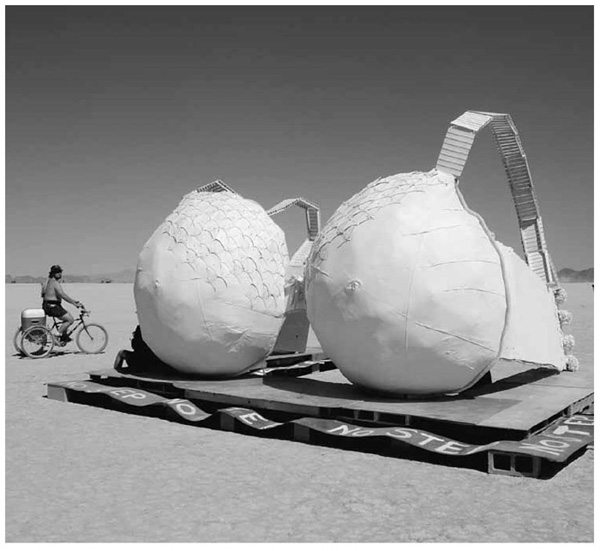

jacket and headscarf, walked us to the trailhead at dawn. She distributed our T-shirts, which read, “Save Second Base,” then wished us well, and gave her mom a tight hug.

Sherrie shouldered her sizeable pack and thundered up the trail. At sixty-seven, she is built like a greyhound, sleek and muscle ripped. When she’s not climbing mountains, she’s a triathlete and ski instructor.

“What are you listening to?” I bellowed into her headphone pods, expecting a flavor of classical.

“Red Jumpsuit Apparatus,” she bellowed back. “I like alternative.”

A couple of hours later, at the summit of Mount Democrat in Colorado’s Mosquito Range, I learned that Sherrie’s nylon pack was like Mary Poppins’s carpet bag. Out came a smorgasbord of honey energy gels, goo packs, and other electrolyte snacks, enough for everyone for this and two more peaks.

Newly fortified, we admired the view. It was a glorious Rocky Mountain day: bluebird sky, granite peaks, patches of white snow sparkling in the sun, triangular green trees far below. For 360 degrees, from 14,148 feet, it was hard to discern any houses or roads. For a moment, it was easy to feel the world was as nature made it.

But then, to the West, what at first looked like a lake revealed itself to be a tailings pond. It was too rectangular and a strange color of turquoise. This was part of the Climax mine, owned by multinational giant Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold. Until recently, the mine was the world’s largest source of molybdenum, a trace element used to harden steel. Now it’s part of a notorious Superfund site. It was hard not to think about the cost of this pollution to the mountains and to our national budget, and then, directly or indirectly, to our breasts.

I’D RATHER JUST LOOK AT LUMINOUS, NEIGHBORING MOUNT

Lincoln, no tailings in view. But this is the cropped way we’ve seen breasts, and it hasn’t done them much good. Scientifically, medically, and culturally, we have preferred to think of them as disembodied objects, removed from the rest of the human body and separate from the rest of nature.

In the early days of cancer treatment, surgeons believed if they could just hack off the tumor-ridden breast, the patient would survive. Alas, even radical mastectomies didn’t usually solve the problem. By the time the cancer was found, it was already invisibly wired to distant parts of the body. But the failure to recognize this cost many women needlessly painful and debilitating procedures. We were also slow to understand that pollutants could end up in breast cells and in breast milk. By insisting that breasts are sexually evolved and relegated to a sexual destiny, we have encouraged women not to value breast-feeding, and sadly, often not to value their normal, natural bodies.

Breasts have only slowly offered up their secrets, and we have been too distracted by their beauty to look very hard. As we’ve learned, breasts aren’t static, or pneumatic. They are always changing.

New bras, new lumps, new pride or despair, new glory, new fear.

WOMEN OFTEN TALK TO ME ABOUT THEIR BREASTS. THEY’LL TELL

me that they’re donating some extra breast milk to a friend in need, or that their brother had breast cancer, or that their breasts are uneven. I’ll tell them about how humans are so unique to have

rounded breasts all of our adult lives, how chimps’ breasts go back to being flat as Frisbees after nursing. “That happened to me!” they might joke. We’ll move on to other topics, like tonsils or tornadoes or

Mrs. Dalloway.

Sooner or later, though, the conversation usually comes back around. Friends and acquaintances ask where I stand on annual mammograms. Am I worried about false-positives? What about the radiation? I tell them the truth, which is that mammography is an archaic and deeply flawed technology, barely improved over fifty years. There are many false-negatives and false-positives, and, yes, there’s radiation, the only proven environmental cause of breast cancer. We can invent the Internet but not something better than blasting ions into our boobs using forty pounds of pressure?

So what do breasts need? ask my friends. Is there hope? Breasts desperately need a rosier future. They need a safer world more attuned to their vulnerabilities, and they need good listeners, not just good oglers. Breasts have some terrific allies, such as mountaineer/chemist Arlene Blum, who is fighting to get flame-retardants out of baby products and out of breast milk, and Susan Love, the brash surgeon who started a nonprofit to fund experimental research using a million human volunteers. Among the promising things Love is looking at: cheap tests of breast fluids to identify women at high risk of cancer. Then there is Rachel Ostroff, research director at SomaLogic. The Boulder-based biotech start-up is trying to identify proteins and enzymes in a routine blood sample that indicate the presence of an early breast tumor. Ostroff, whose sister died of breast cancer, calls these tiny protein biomarkers “the voices of life.” “We want to find the early evidence of disease when a cure is possible and simple,” she said.

These are heartening advances. The medical community is getting better at treating women with breast cancer. In 1944, only 25

percent of women with breast cancer survived ten years; by 2004, the number had increased to 77 percent. Ultimately, though, diagnostics and treatments are already measures of defeat: the tumor has arrived. We can save many women from dying of breast cancer, but that’s not necessarily going to save their breasts. To save breasts— and to spare women the particular agonies of this disease—we need to think more about the bigger picture of health and, ultimately, prevention. Yet surprisingly few national research dollars—about 7 percent of the budget of the National Cancer Institute—are spent on prevention, even broadly defined to include early screening. The cynic in me would point out that actually it’s not that surprising; there is little money to be made in preventing breast cancer compared to screening for it or treating it.

“It’s always been my belief that prevention will help us so much more than a cure,” said Saraswati Sukumar, a Johns Hopkins biochemist. With some help from the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation, she’s pioneering “chemical mastectomies,” injecting chemotherapy through the milk ducts. Currently, the idea is to kill early, proliferating cells and allow women to keep their breasts. But eventually, says Sukumar, the procedure might become part of regular maintenance in high-risk women, akin to regularly cleaning out the pipes, Drano-style.

CALL ME A DREAMER, BUT I’D RATHER HAVE HEALTHY PIPES TO

begin with. This is where prevention gets trickier. On a personal level, it means making vexing choices: drinking less alcohol, seeking alternative menopause treatments, exercising (a lot), scrutinizing labels, and reducing exposures to toxins and endocrine disruptors. These measures will take us only so far. A better and more successful

approach would be a societal one, in which industries have incentives to design safer products and make healthier foods, and governments adopt a commonsense and rigorous approach to testing and regulating chemicals. Social policies could encourage more breast-feeding and less obesity.

Pharmaceutical companies are already working to dethrone standard hormone replacement therapies. Women may soon be able to take a pill that allows estrogen to reach bones and skin but blocks breast cells from picking it up. Similar drugs are in trials now. I’ll admit, though, that I’m skeptical of these solutions. They remind me of altering an ecosystem to benefit one species, such as rainbow trout or Roundup-ready soybeans, only to see harms pop up unexpectedly downstream or downwind.

When it comes to breasts, the ecosystem metaphor is apt. The new sciences of environmental disease and epigenetics are redefining the very notion of human nature. They’re challenging us to recall an ancient belief system that says we are deeply connected to our environment. Twentieth-century medicine had us believe our DNA was our destiny. Now we understand our DNA was built to bend. The pendulum of science is swinging away from the preeminence of the genetic code to the surprising power of our soil, air, water, and food. In this current cultural moment that worships technology and throwaway convenience, it’s a good time to remember our physical interdependence with the larger world. If breasts are to be saved, their salvation will lie in this recognition.

Much about our environment is better than ever. We have fewer parasites and infectious disease; most of us are protected from extreme weather and food shortages. On the whole, people in developed countries are smoking less and living longer than ever before. But when girls reach puberty earlier, their young lives face new and

difficult challenges. Toxins in breast milk run the risk of affecting the cognitive, behavioral, and physical health of our children; and breast cancer will, on average, shave thirteen years off a woman’s life. We now understand health to be more than a measure of longevity. Our goal should be to live the best lives we can.

Decades ago, microbiologist-turned-humanist René Dubos argued for an ecological view of health. Health, he said, was not simply the absence of disease but the ability of the body to adapt to dynamic circumstances. Modern life appears to have compromised that ability in many ways. To safeguard our breasts, we need to protect our bodies’ biological processes. In this sense, the word

ecosystem

is no longer just a metaphor. Breasts

are

an ecosystem, governed by long-evolved functions, migrating molecules, and interconnected parts. Like every ecosystem, this one is highly adaptable, to a point.

Breasts are our sentinel organ. They offer us a window into our rapidly transforming world and the excuse to steward it better.

MUCH LIKE THE MOSQUITO MOUNTAINS, OR FREE-FLOWING RIVERS

or polar ice caps, the human breast is a complex, unique, thrilling, beautiful thing, connected to the world in ways grand and infinitesimal. It’s an evolutionary miracle that we are only beginning to understand.

The fact that we can now talk so freely about breasts means our blind spots are getting smaller. More women are probing the role that industrial chemicals play in polluting our bodies and our breast milk. Every year, more scientific organizations issue proclamations on the need to research and regulate endocrine disruptors. Last year, an esteemed group of international researchers called on regulators in the United States and Europe to stop ignoring mammary

glands when performing studies on lab animals. Those glands, they reminded us, may well be our most informative tissue.

As everybody knows, breasts can speak loudly. When we became aware of chemicals in breast milk, a powerful new lobby of mothers helped sweep DDT and PCBs off the marketplace. The same fate will likely befall brominated flame-retardants. But for scores of other chemicals, the science is young and the regulators often stripped of meaningful power. For the sake of breasts, let’s hope both of these conditions change. In the meantime, consumers have a few more options. Soon it will be possible to buy some kitchen plastics that don’t stimulate the estrogen receptor. Huzzah! It’s a start.

Breast cancer rates declined a few percentage points after 2003, probably because fewer women were taking hormonal replacement therapy. Unfortunately, the decline ended in 2007. Perhaps the HRT effect has gone as far as it will go, or perhaps other factors have started to fill in the vacuum. The search for all the interwoven causes of breast cancer will take a long, long time.

AFTER MY GRANDMOTHER GOT HER RADICAL MASTECTOMY IN

1973, a relative asked her how the wounds were healing. She replied she didn’t know because she refused to look.

There I was, thirty-eight years later, atop a mountain, considering the blue-green splotch of the Climax tailings pond and popping a cherry gel. Sherrie, my indefatigable hiking companion, pulled out her water bottle and camera, and then, slowly, she unfurled her homemade yellow sign for the summit photo: “For Lesley— and for Dan and Alli and for Mom, Bernie, Debbie, Maggie, Dad,

George, Sheila, Stef, Staci, Shawn, For Courage … For Hope, and For Love.”

I’m with her. I didn’t have a sign, but I could have easily shouted down the soft flanks of the Mosquito Mountains that I was there for my daughter, my friends, and my grandmother who refused to look. It’s for them that I wanted to.