Breasts (6 page)

Authors: Florence Williams

Tags: #Life science, women's studies, health, women's health, environmental science

In animals with large litters, the milk lines launch multiple teats on each side. Primates, elephants, horses, cows, and some other mammals get just one set, usually located toward the hind legs. In about one human in a hundred, a vestigial extra nipple or two can show up. Cooper was familiar with these cases, which is why, in his book, he writes, with characteristic judiciousness, “the breasts are generally two in number.”

And of course, Cooper knew all about the inconstancy of breasts. They grow from almost nothing, gradually during childhood and then quite rapidly through adolescence, pregnancy, and lactation. The pace of change slows down again through perimenopause and menopause. The ligaments bearing his name tend to relax over time, and the volume of tissue often decreases as the glandular lobules atrophy (stay tuned for more about this in chapter 13). So, yes, there really is a sag factor, but when and how it happens vary among individuals. The nipples, too, change from small and light in youth to larger and darker in adulthood. From the time we are born, our breasts are on the move.

Cooper did such a thorough job investigating the breast that for the next century or so, no one bothered to learn any more. Until recently, the greatest advances in understanding the mechanics of the mammary gland were made in the dairy field. As to the anatomy of the breast—and the effects on said anatomy from the inexorable march of time—that would eventually undergo some eye-popping revisionism.

Thanks to recent technology, you no longer have to be dead to have someone inject foreign substances into your mammary glands.

FILL HER UP

… but on the fourth night, Ormond chancing to praise the fine shape of one of her very dear friends, Miss Darrell whispered, “She owes that fine shape to a finely padded corset.”

— MARIA EDGEWORTH,

Ormon

B

REASTS MIGHT EXIST FOR THE PURPOSE OF FEEDING

infants, but let’s face it, for most women these days, breasts fulfill that destiny only briefly, if at all. The rest of the time, they sit around trying, sometimes desperately, to look nice. In other primates, “breasts” exist

only

while lactating. For us, lactating is beside the point. Many of us will think nothing of jeopardizing lactation at that other altar of evolution: beauty. Throughout the ages, women have alternately flattened them, buttressed them, veiled them, decorated them, and bared them, sometimes in the course of a day. Now, with enough cash or credit, we can change them for life.

According to the American Society for Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery, 289,000 women went under the knife to enlarge their breasts in 2009, vaulting it to the country’s most popular cosmetic

surgery ahead of nose jobs, eyelid lifts, and liposuction. That figure does not include 113,000 breast reductions in women, 17,000 breast reductions in men, 87,000 “breast lifts,” and 20,000 implant removals. The history of how we got from A to B, or DD, as it were, is a sordid and fascinating tale of marketing, mass hysteria, and environmental disease. To see where we’ve ended up, as well as where it all began, I went to boob job ground zero: houston.

At the swank office suite of Dr. Michael Ciaravino, over eight hundred pairs of breasts a year get the full Texas treatment: silicone, mostly, and a smattering of saline. Ciaravino is a true scion of a storied boob-job lineage, having trained with the doctor who trained with the inventor of implants. An energetic forty-five-yearold, he performs more augmentations by far than any doctor in Texas. His office is where Trump Plaza meets Jiffy Lube. I walked into the white marble sanctum on a crisp winter day. Reflecting the notion that boob jobs are as much about consumerism as medicine, tasteful displays of cosmetics, Ciaravino T-shirts, and a giant poster advertising MemoryGel by Mentor for “superlative enhancement” met me just inside the glass doors. Add to this soft lighting, spotless white and taupe furniture, and arresting megaphotos of women in expensive lingerie.

Dr. C, as he’s known affectionately by staff and patients, had agreed to walk me through the experience as if I were a regular patient. It was all so real, so slick and seductive, so full of metaphorical lotuses that I almost left with a new titanic rack. First, I was greeted by Katye, who genuinely fits the description of blonde bombshell. Like many of the curvy and silken-haired assistants here, she’s been either a swimsuit model or a professional cheerleader. We practically sashayed to a corner office overlooking leafy west Houston, not far from the Galleria mall. Several curvy vases

accented the room’s modernist décor, suggesting shapelier times ahead.

“Welcome to the practice!” Katye began. She told me that Dr. C has been practicing for fourteen years and “has been able to perfect the technique.” She showed me a book of before and after photos, in which (mostly) perfectly nice breasts end up looking like water balloons on a skinny rib cage. These headless torsos did, I have to admit, look much more sexed up in the after shots, since by now we’ve all been conditioned to associate big fake breasts with sex. More on that later.

Katye walked me next door to the 3-D imaging room, where, in the name of journalism, I disrobed. After I comfortably settled into my white waffle-weave robe, she showed me implant samples. They were about the size of a large Krispy Kreme. Both the silicone and saline ones were cased in a round, clear, silicone bag. The silicone implant felt nice and soft in a detached way, like bread dough through Saran Wrap. The saline one felt like a bag of water, which is what it is. Women who wear these sometimes make sloshing noises, and ripples can show through the skin. They are less expensive, though, and may be safer if the implant ruptures. In that case, the breast deflates like a flat tire. When a silicone implant ruptures, it is supposed to stay in place since it has the viscous properties of a gummy bear. This is a vast improvement over the more syrup-like silicones of old.

Dr. Ciaravino came in and introduced himself. He has a broad, tanned face and shoulder-length brown hair. He wore a white lab coat and a thick neck chain. I could easily see him relishing his pastimes, which, according to the office literature, include driving a Porsche and playing electric guitar. I channeled my inner Houston housewife. I told him I’d borne two children, had breast-fed for

years, and after going through life as a size B, was now curious as to what life might be like as a C. He nodded sympathetically. “Let’s have a look,” he said.

The robe came off, and Ciaravino pulled out a small tape measure. He measured me from collarbone to nipple, from nipple to under-breast fold, and from nipple to nipple, calling out numbers to Katye. He took a step back and mashed my breasts together with his hands, then squeezed each one like a club sandwich. I felt like I was awaiting the word of St. Peter. I was secretly hoping one of the world’s foremost experts on flawed breasts would be so vexed by my nice, very normal breasts that he’d tell me he had nothing to offer.

“Well, first off,” he began, “let me say you’d be a great candidate for breast augmentation.” He assessed me some more. “Where you’re lacking a little is some upper fullness here,” he said, referring to the slope above my nipples. “You actually have a decent amount of breast tissue to begin with. We just need to give it a little boost. Silicone would really serve you best. What I would say if we were truly just trying to gain a little upper fullness and enhance its look, we would want to work with implants in a 250 to 275 cc range. This would move you into an average C size.” (Silicone implants from Mentor, for which Ciaravino is a paid consultant, come in a range of about 100 to 800 ccs, or cubic centimeters. Most women in Texas go much bigger than what he was recommending for me. “Big breasts are part of the Texas tradition,” he said. For perspective, some women test sizes by filling sandwich bags with rice: 275 cubic centimeters is the equivalent of 1

1

/

5

cups of rice; 800 cubic centimeters is almost 3

1

/

2

cups of rice.)

Ciaravino then led me to his new $40,000 Vectra imaging

machine, which would simulate how the implants would look in my breasts. He ducked out, and I, still half-naked, stood motionless in front of the small-saguaro-sized device, with its white plastic trunk and arms, while it captured me in 3-D. Katye clicked a mouse on a computer and then told me I could get dressed behind a small curtain. Soon an image of my torso popped up on her monitor, and together we watched while she punched in some magic codes. Two images appeared on the monitor, me with my real B-plus breasts and then me with big breasts getting bigger and bigger.

“Oh my God,” I said to the screen. I was va-va-voom. But not in a good way. My breasts were big and pendulous and pointing outward. My nipples had the strabismic look of a walleye.

Dr. C popped back into the room and looked at the monitor.

“Oh, that’s huge,” he said.

“I kind of have a sideways thing going on,” I said.

“Yeah, that doesn’t look too good. I would back it up to about half of that,” he told Katye at the controls. “Keep going, keep going.” My cyber boobs were shrinking before my eyes. “Sometimes the machine distorts things,” he explained. “Your nipples won’t really go out like that.” Katye next brought up the profile images, which looked much better. Instead of my breasts having the regrettable ski slope above the nipple (something I never noticed before), now they had the curves of an upside-down cereal bowl.

“You’ll do wonderful,” said Dr. C.

THERE’S NOTHING LIKE AMERICA’S CONSUMER CULTURE TO

convince us that what we have isn’t quite good enough. We didn’t used to be this way. Americans have traditionally been tough

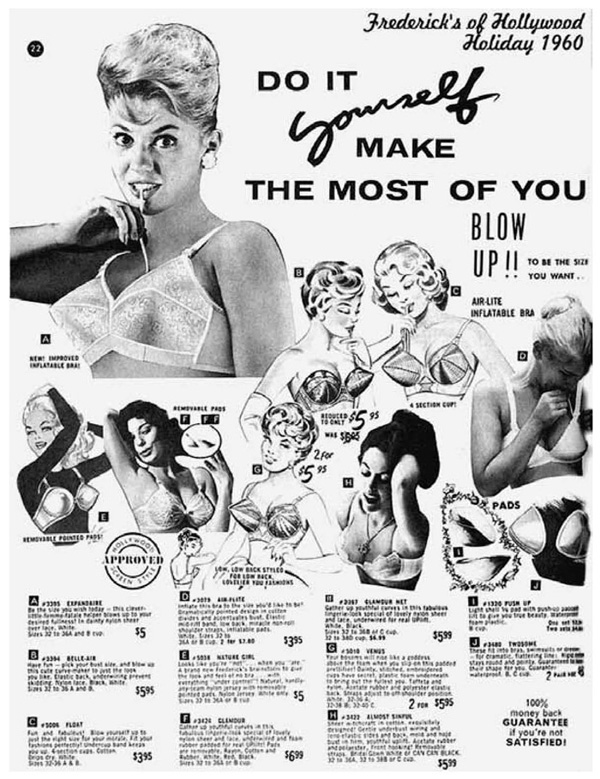

skinned and self-reliant. At the same time, of course, we’ve been great reinventors of the self. Hollywood may celebrate the heroes of the former, but its images reinforce the latter. In breasts, these two strains of character found a new tension by the middle of the last century. Somewhere along the line, lured by Jean Harlow and Jayne Mansfield and the technological promise of postwar America, American women tossed out the make-do-with-what-you-have mentality and embraced a burning desire for outsized nose-cones.

Highly engineered bras helped, but only if you had something to put in them. Kleenex was popular, and so were socks. Falsies, made out of wire, sheet metal, papier-mâché, rubber, cork, elk hair, or cotton, became a multimillion-dollar industry. In its 1951 catalog, Sears offered twenty-two different versions. At that time, surgical solutions to a larger bust were dangerous and rare. Many more breast reductions were performed than breast augmentations. For much of Western history, large breasts were considered a burden and a handicap. Consider the case of poor Elisabeth Trevers, a young Englishwoman who, according to her surgeon, woke up one morning in 1669 “and attempted to turn herself in bed, [but] she was not able … Then endeavoring to sit up, the weight of the breasts fastened her to her bed; where she hath layn ever since.”

Augmentation came later. Although inserting foreign objects into the body was known to be dangerous, there were always some surgeons and women willing to experiment. The first boob job is attributed to Vincenz Czerny, a Heidelberg physician. He transplanted a benign fatty growth from the backside of a forty-one-year-old singer to her chest in 1895. It was a good idea, since the material came from her own body and was less likely to cause an

immune-system rejection, but the result was lumpy and, because the fat liquefied, temporary. That was failure number one.

From that point on, the backstory of implants reads like a horror novel.

In the early twentieth century, implant materials included glass balls, ivory, wood chips, peanut oil, honey, goat’s milk, and ox cartilage. What became of the (thankfully few) women who volunteered for these leaps of science? The parable of paraffin offers a glimpse. From the mid-nineteenth century, paraffin injections had been used on facial deformities. Sadly, there was plenty of opportunity; both war and syphilis—which depressed the nose—were great for advancing the art of plastic surgery. Inevitably, the wax was injected into the breast. But by 1920, its limitations were well known. It melted in the sun, for one. It also created lumps and tumors called paraffinomas that eventually had to be excised out, leaving scars. Beyond that, other problems were puss, hardness, blue skin, and feverish rheumatism. At least one woman’s infected breasts had to be amputated. As one historian put, the disadvantages of paraffin ranged from aesthetic failure to death.

Of course, women going to dangerous extremes for beauty was hardly new. For a thousand years Chinese women crippled themselves and their daughters to have tiny, deformed feet. Western women literally suffocated while wearing corsets, some of which punctured their internal organs. Women have painted their faces with lead and arsenic and ripped their body hair off with hot wax. Oh, wait, we still do that.

Into this sorry milieu came the plastics revolution and a new breed of unholy implant contenders: Teflon, nylon, and Plexiglas. Several surgeons were moved by the shape of plastic kitchen sponges.

In 1957 a Johns Hopkins surgeon implanted a polyvinyl and polyethylene sponge (also made with “foaming agents” and formaldehyde) called the Ivalon into thirty-two women. As one magazine reported at the time, “The material’s one drawback is that when it dries inside the breast it becomes a hard lump.”

Meanwhile, toiling in a laboratory in Midland, Michigan, chemists were experimenting with different uses for a versatile material called silicone. Corning Glass Works had begun fooling around with the stretchy composite in the 1930s, making it from silicon (an element) left over from its glass production. To this they added organic carbon-based chemicals in various configurations, resulting in a material that was pretty close to miraculous: hardy, inert, and heat resistant, yet soft and flexible. It was a glass-and-plastic hybrid, with the best properties of both. The company thought it might make a good mortar for its trendy glass bricks (they were wrong, but the failed formulation found new life two decades later as Silly Putty). At the beginning of World War II, U.S. Navy officials coveted a similar formulation of silicone, finding it perfect for insulating airplane ignitions (it made long flights to Europe possible) and for lubricating machinery. To guarantee larger supplies of the carbonbased ingredients, Corning partnered with Dow Chemical in 1943 to form a new war-christened giant, Dow Corning, in the American heartland.

When the war ended, Dow Corning was eager for new civilian markets for wartime products. The company began ardently filing patents for silicone polishes and paints, adhesives, silicone shoe rubber (astronaut Neil Armstrong would take a giant step in it in 1969), caulking, and other applications. The medical profession was intrigued by silicone’s strength, flexibility, and apparent

non-reactivity, and slowly the material made its way into catheters, stents, tubing, and blood bags.

In American-occupied Japan, another, less orthodox use was found for silicone. Drums of the stuff, needed for cooling transformers, went missing from the docks of Yokohama harbor. It turned up in the breasts of Japanese prostitutes, who were being injected with it to better attract enlisted farm boys. The technique spread through eastern Asia and became one of Japan’s most popular exports to the United States. But as with paraffin, the industrial caulk-like material was known to migrate throughout the body, form hard lumps, and cause serious infections.

Back in Houston, plastic surgeon Thomas Cronin was holding a new silicone bag of warm blood in St. Joseph Hospital. It was 1959, and the blood bags were a nice change from glass bottles.

My,

he thought,

that feels good. That feels like a breast.