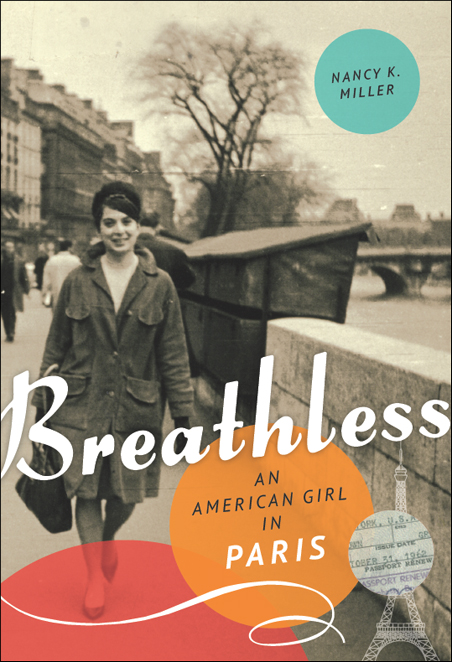

Breathless

Authors: Nancy K. Miller

BREATHLESS

An American Girl in Paris

Copyright © 2013 Nancy K. Miller

Published by

Seal Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

1700 Fourth Street

Berkeley, California

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Miller, Nancy K., 1941-

Breathless : an American girl in Paris / by Nancy K. Miller.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-58005-489-8

1. Miller, Nancy K., 1941- 2. Americans—France—Paris—Biography. 3. Young women—France—Paris—Biography. 4. Coming of age—Case studies. 5. Autonomy—Case studies. 6. Miller, Nancy K., 1941—Relations with men. 7. Paris (France)—Biography. 8. Paris (France)—Social life and customs—20th century. 9. Young women—New York (State)—New York—Biography.

I. Title.

DC705.M55A3 2013

944’.3610836092—dc23

[B]

2013016144

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

Cover design by Kimberly Glyder

Interior design by Domini Dragoone

Eiffel Tower art © sarella/123rf, fleur de lys art © Victor Kunz/123rf

Distributed by Publishers Group West

For Kamy Wicoff

Contents

Why Is It So Hard to Be Happy?

“Qu’est-ce que c’est, dégueulasse?”

Y

OU NEVER GET OVER YOUR

first great love, Colette says in one of her novels, alluding to the wounds inflicted by the first of her three husbands. Tucked away in a secret compartment, that kind of hurt lives on—a permanent resident with a lifetime visa. How could the circuits of hope have collapsed so quickly, you wonder, stunned by the evidence of your misery? When did the paths leading to the happy ending veer off into a labyrinth of despair? The answers never match the questions. You just know that you won’t ever be the same. Eventually, that’s the good news. I never got over Paris. In the beginning, the pain of separation was acute, but in the end I’ve found a way to make a story out of it. After a while, of course, you believe the story you tell about your life. True story, the author says on the book jacket. In other words, before it was a story, it was also real.

I went to Paris because I was enamored of the sexy nouvelle vague movies, which, like the eighteenth-century novels I had read in college,

offered entry into scenarios of freedom barred to me as long as I lived at home. I wanted to smoke in a Left Bank café. I wanted to be sophisticated and daring, nothing like my nice-Jewish-girl self and her nice Jewish parents from whom I longed to escape. But the strangest thing—and I was quite blind to the paradox then—was that in going to Paris I wound up even more hopelessly entangled with my parents, who had made Paris a world of their own well before I arrived on the scene. In the end, I had to leave Paris, if I wanted to be free.

I’ve been haunted by the girl in this book for most of my life. Now that those years of the 1960s when Paris loomed so large on my fantasy screen are securely locked away in the past, and reordered by memory, I’ve finally come to see her as someone I can forgive for trying so hard to become someone she was never meant to be: an eighteenth-century marquise, or more modernly, a girl whose wardrobe included a striped Dior shirtwaist dress.

I

DIDN

’

T

SET OUT TO

sleep with Philippe. For one thing, he was my parents’ friend; for another, he was married.

On one of their many trips to Paris before I lived there, my parents met Philippe Roussel, an ophthalmologist, at Aux Charpentiers, a neighborhood restaurant near Saint-Germain des Près, where long, family-style tables bring you into closer contact with other diners than you might wish. In his travel diary, which I discovered after his death, my father reported that the French friends who had recommended the restaurant had said that “while not modern or elegant it was a place where intellectuals came to eat.”

My parents were all for intellectuals, as long as I didn’t marry one. And while traveling in France, which they had been doing since the mid-1950s, they prided themselves on eating at restaurants not listed in the

Michelin Guide

. Sitting across the narrow table, the doctor noticed my father putting drops into his bloodshot eyes. He struck up a conversation

with my parents, offering his professional services. After dinner they all went back to his office around the corner on the rue Jacob, where the eye doctor treated my father by injection. As if that were not enough (“This could only happen to me,” my father noted in a rare burst of personal reporting), Philippe then invited my parents into his living quarters adjacent to the office for drinks and music. Philippe, it turned out, was not only a great eye doctor but a brilliant pianist. He played from memory for an hour. The music so moved my father that he crushed the wine glass he was holding in his hand. The following year, when they became better acquainted, Philippe played tennis with my mother, who was not accustomed to losing, and beat her 6–2, 6–2, 6–4, “a fine game,” according to the diary entry, despite the score.

I never knew what I liked most about the story, which my father had told more than once: my father having his eye injected by a total stranger, or my father so stirred by Schubert that he broke a glass listening to the music.

W

HEN

I

ARRIVED IN

P

ARIS

in the early fall of 1961 to study at the Sorbonne, I made an appointment to see Philippe about my contact lens prescription. A few weeks later he invited me to a party at his apartment. The following day, when I got back from my job teaching English at a lycée for girls, I found his card with a message scrawled in brown ink:

“N. Vous avez fait des ravages.”

The ravaged victim of my charms turned out to be a Japanese painter who had been passing through Paris. He wanted to practice his English over dinner, but I wasn’t in the mood for more lessons. Within the week, Philippe invited me out to dinner himself. We drove to Montparnasse in his red Volkswagen convertible with the top up and his hand under my skirt.

I wasn’t completely surprised to find Philippe’s hand creeping nimbly under my garter belt. I had already been initiated into this practice by Monsieur Delattre, the phonetics professor, during the summers I spent at Middlebury College’s French School, where all the students signed a Language Pledge—

un engagement d’honneur

—not to speak a word of English for six weeks, under threat of expulsion. We were willing

prisoners of the Pledge, endlessly correcting each other, alert to the slightest infraction, even while kissing. “Perfecting” our French was the fantasy that inspired compliance.

Monsieur Delattre would pick me up at my boarding house and we would go for long drives late at night down deserted country roads. I learned French slang words for penis—

queue

and

verge

, surprised that they were feminine nouns, while

con

, “cunt,” was masculine, and also meant a guy who was a jerk—with no clue that nice girls were not supposed to know those expressions, certainly not use them. I cared only about my accent and getting the gender right. I justified the fingers by the phonetics. As it turned out, the French professor’s hand-in-the-crotch-while-driving routine on Vermont country roads proved to be excellent preparation for my first year in Paris. I almost didn’t mind being another stop on a stick shift. There was something seductive and guiltless about being a good pupil.

After an extra rare steak au poivre washed down with a bottle of Saint-Julien at the Coupole, we drove back to Philippe’s apartment. He poured champagne for both of us and played a late Schubert sonata, cigarette drooping French-style from his mouth, the ash dropping slowly over the piano keys. I didn’t break a glass, but I was impressed. Philippe had hesitated between the conservatory and medical school, he told me. A little after eleven o’clock, he stopped playing and suggested—very quietly—that I spend the night. I can’t say that I found Philippe physically attractive—tall, thin, with a long beaky nose and thin lips—but he somehow forced you to like his ugliness.