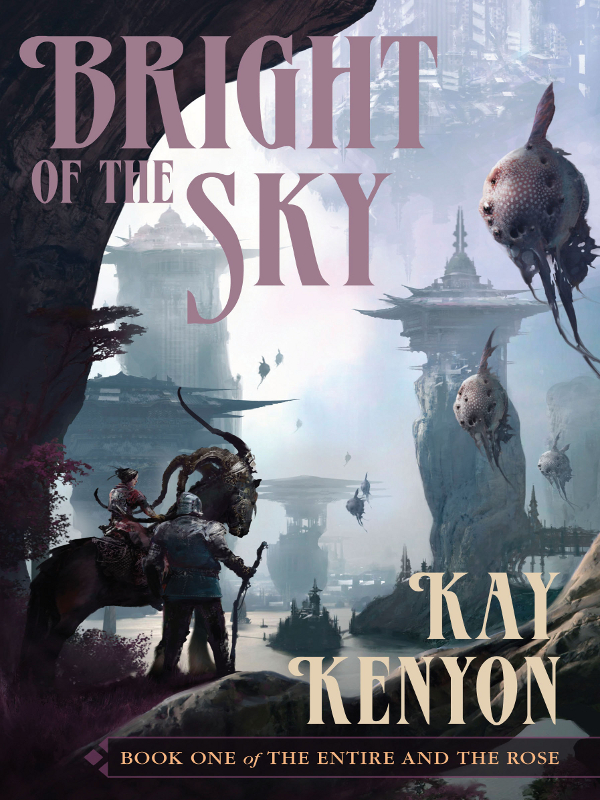

Bright of the Sky

Authors: Kay Kenyon

BRIGHT

OF THE

S

KY

BRIGHT

OF THE

SKY

KAY

KENYON

BOOK ONE

of

THE ENTIRE AND THE ROSE

Published 2007 by Pyr

®

, an imprint of Prometheus Books

Bright of the Sky

. Copyright © 2007 by Kay Kenyon. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a Web site without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Inquiries should be addressed to

Pyr

59 John Glenn Drive

Amherst, New York 14228–2197

VOICE: 716–691–0133, ext. 207

FAX: 716–564–2711

WWW.PYRSF.COM

11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kenyon, Kay.

Bright of the sky / Kay Kenyon.

p. cm. — (The entire and the rose ; bk. 1)

ISBN 978–1–59102–541–2 (alk. paper)

I. Title.

PS3561.E5544B75 2007

813'.6—dc22

2007001608

Printed in the United States on acid-free paper

For Mike Resnick

CONTENTS

M

ANY THANKS TO THE EARLY READERS

of this manuscript: Karen Fishler; Barry Fishler; Gary Nunn; Barry Lyga; and, as always, my husband, Tom Overcast. Their comments and suggestions greatly improved the story and saved me from embarrassing lapses. Bravo for those who take on a first read! Barry Lyga was kind enough to read the novel twice, and my husband, well—we’ve lost count. I am grateful for the insights offered by Robert Metzger, although I took liberties with the science above and beyond all advice. I am indebted to my agent, Donald Maass, for big-picture perspectives that can be lost in the tangle of pages. His belief in this story played a major role in keeping me on task in writing the first book and keeping faith with the coming three. During these years of concentration on The Entire and the Rose, I benefited greatly from the support and wisdom of Mike Resnick. Coincidentally, it was Mike who first collaborated with me on a short story sold to an editor I hadn’t worked with before, Lou Anders. I am delighted to team with Lou and Pyr for the debut of my first series.

Storm wall, hold up the bright,

Storm wall, dark as Rose night,

Storm wall, where none can pass,

Storm wall, always to last.

—a child’s verse

M

ARCUS SUND CAME AWAKE ALL AT ONCE

. “Lights,” he said.

The cabin remained dark. “Lights,” he repeated, louder this time, but with the same result. He sat up. The station hummed with life support—the ProFabber engines churned in their colossal duties—but something was missing from that profound vibration.

He dressed hurriedly, toggling the operations deck as he yanked his shirt on. “Report.”

“Sir, we have some minor failures in noncritical functions. We’re on it.”

Marcus left his cabin and hurried down the corridor. The lights browned and surged back again. The station exec knew his rig, down to the last bolt and data structure, and therefore he could feel through the soles of his feet that the hum was wrong, the vibration of the carbon polysteel deck plates a few cycles off. That worried him far more than the flickering lights.

The station’s military-grade ProFabber engines simultaneously churned out artificial gravity and monitored the Kardashev tunnel, calming it for company business—the business of interstellar travel. With such critical functions, the engines were under the control of the on-station machine sapient. Thus, if engine performance fell even slightly, and if the system hadn’t alerted Marcus Sund by now, that meant the mSap—the station’s sole machine sapient—was not paying attention. It was unthinkable that the machine sapient was not paying attention.

They were far from home. The Appian II space platform orbited a stellar-mass black hole, stabilizing it. From their position deep in the Sagittarius arm of the Milky Way near the Eagle nebula, the Earth’s sun appeared as a mere dot in the constellation Taurus. Even with Kardashev tunnel transport, the Appian II depended utterly on the station and the twenty-third century AI that ran it. The platform contained living quarters for 103 crew, an advanced research laboratory, and Marcus Sund’s entire career.

As Marcus approached station ops, twenty-year-old Helice Maki met him in the corridor. Six years ago she had been the youngest graduate in the history of the Stanford sapience engineering program, a fact that she mentioned with annoying frequency. He didn’t like her, but he needed her now. By the expression on her face, she felt it too—that something was wrong.

“I’m going in,” she said, nodding at the Deep Room, site of the interface with the quantum sapient.

“Go,” he said. The sapient had better not be in trouble, but if it was, Helice Maki could deal with it.

With a sickening blare, the klaxons burst to life. As Helice disappeared into the Deep Room, Marcus rushed to the operations suite a few doors down. Here, tenders were on task, deadly serious. The deputy exec reported that in the last two minutes, the ProFabber engines had powered down to maintenance level, abandoning the K-tunnel. It could hardly be worse news, not because the tunnel had to work, but because the mSap had to. They were dead without it.

“Lock out the mSap from expert systems,” Marcus ordered. He had to nod at his deputy to reinforce the order. They were isolating themselves from their central computation resource, a logic device with perhaps limitless capabilities. Now they must fall back on the workhorse savants—simple tronic computers, wickedly fast, duller than stumps. The K-tunnel as a transport route was off-limits for now, but they could clean it up later. They could get through this, Marcus thought, while the word

runaway

kept stabbing at him.

From the Deep Room, Helice’s voice came over the comm, throaty with emotion. “Get in here, Marcus.”

Ops was erupting with reports from all stations, all decks:

Tronic systems

failing; K-tunnel functions, off-line; extravehicular communication arrays, off-line;

life-support systems moved to auxiliary power. Onboard host experiments terminated;

memory caches dumping data, slaved to the mSap for incoming data.

The deputy exec turned to Marcus. “The mSap is hijacking storage capacity from every embedded data structure on station, and slaving it to itself, commanding all station power, and locking out both human and savant overrides.”

Runaway.

Marcus brushed the thought aside.

But people in the room heard the assessment, and exchanged glances of disbelief. Not one of them, including Marcus, had ever seen a rogue machine sapient. Stories had it that once an mSap got away from its handlers, it could quickly form goals of its own—a chaotic state known as

obsession

. Pray God this mSap had not acquired one.

Leaving his deputy in charge, Marcus hurried down the corridor to the sapient domain, took a chair in the anteroom, and punched up a screen so that he could see Helice Maki at work inside the Deep Room.

She came on-screen, talking to him as she worked the sapient. “Secure this channel.” He obeyed.

Surrounded by the simulated quantum output, and talking in the sapient code language, she pointed her indexed thumb at sections of the sapient’s mind-field. To Marcus, it looked like she was dancing—or conducting a symphony.

In between code talk, Helice spoke softly to him: “It’s an incursion. We have a worm loose in here.”

“That’s not possible,” Marcus snapped. He’d never used such a tone with Helice Maki before, especially given the rumors of her impending installation as a company partner.

She ignored him. “There are missing responses, rogue strands. I’m beginning error correction.”

“Don’t do that; we’ll lose everything.” It had taken three years to coach this mSap to oversee a space platform. Retraining it would be an ugly smear on his reputation.

“We’ve already lost everything. It’s on a mission, and it’s not mine. Or yours. Isolate the savants from this rogue.”

“I’ve already done that.”

“Okay, okay,” she said, preoccupied. She pointed her hand where she wished to retrain, talking the gibberish of the sapient engineer, looking almost ecstatic, like a believer getting a dose of Jesus.

As he waited for her, he tapped into the comm. “Report.”

“Marcus, we’ve got an imminent life-support failure on deck four. If we evacuate, we’ll lose connection with the main nutrition fabber.”

Food was the least of his worries right now. “Evacuate. Take all self-contained life suits off the deck.” He knew how that sounded. Like they’d need them.

The sapient grooming staff trickled in, leaning against the wall in the small anteroom, waiting to help—or to throw themselves on the funeral pyre. Anjelika Denhov arrived first, with three postdocs trailing her, looking ill. Their research had been running on the mSap. They could pray they hadn’t touched off this disaster.

Marcus saw his career imploding. He thought they’d live through this— Christ, this was a Minerva Company main K-tunnel station, of course they would survive—but his career was over. On his watch, they were abandoning a deck, yanking critical science lab work, dumping all data, and, worst, retraining an mSap. His stomach tumbled in free fall, like his career, heading to a permanent landing in the warrens of the damned. There, the majority of people were unemployed, living off the dole, feeding on the Basic Standard of Living and virtual entertainments, sustained by the wealth of the Companies— the behemoth economic blocs that fueled the world. His parents took the dole, and all his siblings, and all his cousins. He was the only one who had tested strongly enough to groom the sapients, and then, groom the groomers. He had risen high. Looking down, he could see how high.

From the screen, Helice had stopped her dance. “Oh my God.”

After a beat Marcus prodded, “What, what is it?”

She stepped in closer to the knot in the display, a tangle of virtual quantum waves. She mumbled something in code. Then: “It’s a simple evolutionary.” She turned toward the optic and said, “Someone’s let loose a goddamned evolutionary program. And it’s in its three hundred and ninth generation.”