Bully for Brontosaurus (33 page)

Read Bully for Brontosaurus Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Jimmy Carter, if I understand his religious attitudes properly, upholds an unconventional point of view among Christian intellectuals on the issue of relationships between God and nature. Most theologians (in agreement with most scientists) now argue that facts of nature represent a domain different from the realm of religious attitudes and beliefs, and that these two worlds of equal value interact rather little. But Jimmy Carter is a twentieth-century natural theologian—that is, he accepts the older argument, popular before Darwin, that the state of nature should provide material for inferring the existence and character of God. Nineteenth-century versions of natural theology, as embodied in Paley’s classic work (1802) of the same name, tended to argue that God’s nature and benevolence were manifest in the excellent design of organisms and the harmony of ecosystems—in other words, in natural goodness. Such an attitude would be hard to maintain in a century that knew two world wars, Hiroshima, and the Holocaust. If natural theology is to be advanced in our times, a new style of argument must be developed—one that acknowledges the misfits, horrors, and improbabilities, but sees God’s action as manifest nonetheless. I think that Carter developed a brilliant twentieth-century version of natural theology by criticizing my book in the next paragraph of his letter:

You seem to be straining mightily to prove that everything that has happened prior to an evolutionary screening period was just an accident, and that if the tape of life was replayed in countless different ways it is unlikely that cognitive creatures would have been created or evolved. It may be that when you raise “one chance in a million” to the 4th or 5th power there comes a time when pure “chance” can be questioned. I presume that you feel more at ease with the luck of 1 out of 10 to the 30th power than with the concept of a creator who/that has done some orchestrating.

In other words, Carter asks, can’t the improbability of our evolution become so great that the very fact of its happening must indicate some divine intent? One chance in ten can be true chance, but the realization of one chance in many billion might indicate intent. What else could a twentieth-century natural theologian do but locate God in the realization of improbability, rather than in the ineffable beauty of design!

Carter’s argument is fascinating but, I believe, wrong—and wrong for the same reason that James invokes against Shaler (the central point of this essay). In fact, Carter’s argument is Shaler’s updated and more sophisticated. Shaler claimed that God must have superintended our evolution because the derailment or disruption of any of thousands of links in our evolutionary chain would have canceled the possibility of our eventual appearance. James replied that we cannot read God in contingencies of history because a probability cannot even be calculated for a singular occurrence known only after the fact (whereas probabilities could be attached to predictions made at the beginning of a sequence). James might as well have been answering Carter when he wrote to Shaler:

But your argument that it is millions to one that it didn’t do so by chance doesn’t apply. It would apply if the witness had preexisted in an independent form and framed his scheme, and then the world had realized it. Such a coincidence would prove the world to have a kindred mind to his. But there has been no such coincidence. The world has come but once, the witness is there after the fact and simply approves…. Where only one fact is in question, there is no relation of “probability” at all.

Such is our intellectual heritage, such our continuity, that fine thinkers can speak to each other across the centuries.

IN LATE

1909, two great men corresponded across oceans, religions, generations, and races. Leo Tolstoy, sage of Christian nonviolence in his later years, wrote to the young Mohandas Gandhi, struggling for the rights of Indian settlers in South Africa:

God helps our dear brothers and co-workers in the Transvaal. The same struggle of the tender against the harsh, of meekness and love against pride and violence, is every year making itself more and more felt here among us also.

A year later, wearied by domestic strife, and unable to endure the contradiction of life in Christian poverty on a prosperous estate run with unwelcome income from his great novels (written before his religious conversion and published by his wife), Tolstoy fled by train for parts unknown and a simpler end to his waning days. He wrote to his wife:

My departure will distress you. I’m sorry about this, but do understand and believe that I couldn’t do otherwise. My position in the house is becoming, or has become, unbearable. Apart from anything else, I can’t live any longer in these conditions of luxury in which I have been living, and I’m doing what old men of my age commonly do: leaving this worldly life in order to live the last days of my life in peace and solitude.

The great novelist Leo Tolstoy, late in life.

THE BETTMANN ARCHIVE

.

But Tolstoy’s final journey was both brief and unhappy. Less than a month later, cold and weary from numerous long rides on Russian trains in approaching winter, he contracted pneumonia and died at age eighty-two in the stationmaster’s home at the railroad stop of Astapovo. Too weak to write, he dictated his last letter on November 1, 1910. Addressed to a son and daughter who did not share his views on Christian nonviolence, Tolstoy offered a last word of advice:

The views you have acquired about Darwinism, evolution, and the struggle for existence won’t explain to you the meaning of your life and won’t give you guidance in your actions, and a life without an explanation of its meaning and importance, and without the unfailing guidance that stems from it is a pitiful existence. Think about it. I say it, probably on the eve of my death, because I love you.

Tolstoy’s complaint has been the most common of all indictments against Darwin, from the publication of the

Origin of Species

in 1859 to now. Darwinism, the charge contends, undermines morality by claiming that success in nature can only be measured by victory in bloody battle—the “struggle for existence” or “survival of the fittest” to cite Darwin’s own choice of mottoes. If we wish “meekness and love” to triumph over “pride and violence” (as Tolstoy wrote to Gandhi), then we must repudiate Darwin’s vision of nature’s way—as Tolstoy stated in a final plea to his errant children.

This charge against Darwin is unfair for two reasons. First, nature (no matter how cruel in human terms) provides no basis for our moral values. (Evolution might, at most, help to explain why we have moral feelings, but nature can never decide for us whether any particular action is right or wrong.) Second, Darwin’s “struggle for existence” is an abstract metaphor, not an explicit statement about bloody battle. Reproductive success, the criterion of natural selection, works in many modes: Victory in battle may be one pathway, but cooperation, symbiosis, and mutual aid may also secure success in other times and contexts. In a famous passage, Darwin explained his concept of evolutionary struggle (

Origin of Species

, 1859, pp. 62–63):

I use this term in a large and metaphorical sense including dependence of one being on another, and including (which is more important) not only the life of the individual, but success in leaving progeny. Two canine animals, in a time of dearth, may be truly said to struggle with each other which shall get food and live. But a plant on the edge of a desert is said to struggle for life against the drought…. As the mistletoe is disseminated by birds, its existence depends on birds; and it may metaphorically be said to struggle with other fruit-bearing plants, in order to tempt birds to devour and thus disseminate its seeds rather than those of other plants. In these several senses, which pass into each other, I use for convenience sake the general term of struggle for existence.

Yet, in another sense, Tolstoy’s complaint is not entirely unfounded. Darwin did present an encompassing, metaphorical definition of struggle, but his actual examples certainly favored bloody battle—“Nature, red in tooth and claw,” in a line from Tennyson so overquoted that it soon became a knee-jerk cliché for this view of life. Darwin based his theory of natural selection on the dismal view of Malthus that growth in population must outstrip food supply and lead to overt battle for dwindling resources. Moreover, Darwin maintained a limited but controlling view of ecology as a world stuffed full of competing species—so balanced and so crowded that a new form could only gain entry by literally pushing a former inhabitant out. Darwin expressed this view in a metaphor even more central to his general vision than the concept of struggle—the metaphor of the wedge. Nature, Darwin writes, is like a surface with 10,000 wedges hammered tightly in and filling all available space. A new species (represented as a wedge) can only gain entry into a community by driving itself into a tiny chink and forcing another wedge out. Success, in this vision, can only be achieved by direct takeover in overt competition.

Furthermore, Darwin’s own chief disciple, Thomas Henry Huxley, advanced this “gladiatorial” view of natural selection (his word) in a series of famous essays about ethics. Huxley maintained that the predominance of bloody battle defined nature’s way as nonmoral (not explicitly immoral, but surely unsuited as offering any guide to moral behavior).

From the point of view of the moralist the animal world is about on a level of a gladiator’s show. The creatures are fairly well treated, and set to fight—whereby the strongest, the swiftest, and the cunningest live to fight another day. The spectator has no need to turn his thumbs down, as no quarter is given.

But Huxley then goes further. Any human society set up along these lines of nature will devolve into anarchy and misery—Hobbes’s brutal world of

bellum omnium contra omnes

(where

bellum

means “war,” not beauty): the war of all against all. Therefore, the chief purpose of society must lie in mitigation of the struggle that defines nature’s pathway. Study natural selection and do the opposite in human society:

But, in civilized society, the inevitable result of such obedience [to the law of bloody battle] is the re-establishment, in all its intensity, of that struggle for existence—the war of each against all—the mitigation or abolition of which was the chief end of social organization.

This apparent discordance between nature’s way and any hope for human social decency has defined the major subject for debate about ethics and evolution ever since Darwin. Huxley’s solution has won many supporters—nature is nasty and no guide to morality except, perhaps, as an indicator of what to avoid in human society. My own preference lies with a different solution based on taking Darwin’s metaphorical view of struggle seriously (admittedly in the face of Darwin’s own preference for gladiatorial examples)—nature is sometimes nasty, sometimes nice (really neither, since the human terms are so inappropriate). By presenting examples of all behaviors (under the metaphorical rubric of struggle), nature favors none and offers no guidelines. The facts of nature cannot provide moral guidance in any case.

But a third solution has been advocated by some thinkers who do wish to find a basis for morality in nature and evolution. Since few can detect much moral comfort in the gladiatorial interpretation, this third position must reformulate the way of nature. Darwin’s words about the metaphorical character of struggle offer a promising starting point. One might argue that the gladiatorial examples have been over-sold and misrepresented as predominant. Perhaps cooperation and mutual aid are the more common results of struggle for existence. Perhaps communion rather than combat leads to greater reproductive success in most circumstances.

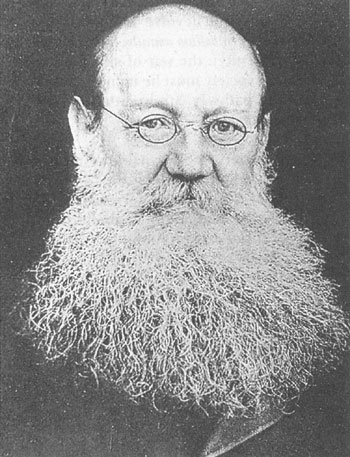

Petr Kropotkin, a bearded but gentle anarchist.

THE BETTMANN ARCHIVE

.

The most famous expression of this third solution may be found in

Mutual Aid

, published in 1902 by the Russian revolutionary anarchist Petr Kropotkin. (We must shed the old stereotype of anarchists as bearded bomb throwers furtively stalking about city streets at night. Kropotkin was a genial man, almost saintly according to some, who promoted a vision of small communities setting their own standards by consensus for the benefit of all, thereby eliminating the need for most functions of a central government.) Kropotkin, a Russian nobleman, lived in English exile for political reasons. He wrote

Mutual Aid

(in English) as a direct response to the essay of Huxley quoted above, “The Struggle for Existence in Human Society,” published in

The Nineteenth Century

, in February 1888. Kropotkin responded to Huxley with a series of articles, also printed in

The Nineteenth Century

and eventually collected together as the book

Mutual Aid

.

As the title suggests, Kropotkin argues, in his cardinal premise, that the struggle for existence usually leads to mutual aid rather than combat as the chief criterion of evolutionary success. Human society must therefore build upon our natural inclinations (not reverse them, as Huxley held) in formulating a moral order that will bring both peace and prosperity to our species. In a series of chapters, Kropotkin tries to illustrate continuity between natural selection for mutual aid among animals and the basis for success in increasingly progressive human social organization. His five sequential chapters address mutual aid among animals, among savages, among barbarians, in the medieval city, and amongst ourselves.

I confess that I have always viewed Kropotkin as daftly idiosyncratic, if undeniably well meaning. He is always so presented in standard courses on evolutionary biology—as one of those soft and woolly thinkers who let hope and sentimentality get in the way of analytic toughness and a willingness to accept nature as she is, warts and all. After all, he was a man of strange politics and unworkable ideals, wrenched from the context of his youth, a stranger in a strange land. Moreover, his portrayal of Darwin so matched his social ideals (mutual aid naturally given as a product of evolution without need for central authority) that one could only see personal hope rather than scientific accuracy in his accounts. Kropotkin has long been on my list of potential topics for an essay (if only because I wanted to read his book, and not merely mouth the textbook interpretation), but I never proceeded because I could find no larger context than the man himself. Kooky intellects are interesting as gossip, perhaps as psychology, but true idiosyncrasy provides the worst possible basis for generality.

But this situation changed for me in a flash when I read a very fine article in the latest issue of

Isis

(our leading professional journal in the history of science) by Daniel P. Todes: “Darwin’s Malthusian Metaphor and Russian Evolutionary Thought, 1859–1917.” I learned that the parochiality had been mine in my ignorance of Russian evolutionary thought, not Kropotkin’s in his isolation in England. (I can read Russian, but only painfully, and with a dictionary—which means, for all practical purposes, that I can’t read the language.) I knew that Darwin had become a hero of the Russian intelligentsia and had influenced academic life in Russia perhaps more than in any other country. But virtually none of this Russian work has ever been translated or even discussed in English literature. The ideas of this school are unknown to us; we do not even recognize the names of the major protagonists. I knew Kropotkin because he had published in English and lived in England, but I never understood that he represented a standard, well-developed Russian critique of Darwin, based on interesting reasons and coherent national traditions. Todes’s article does not make Kropotkin more correct, but it does place his writing into a general context that demands our respect and produces substantial enlightenment. Kropotkin was part of a mainstream flowing in an unfamiliar direction, not an isolated little arroyo.