Bully for Brontosaurus (47 page)

Read Bully for Brontosaurus Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

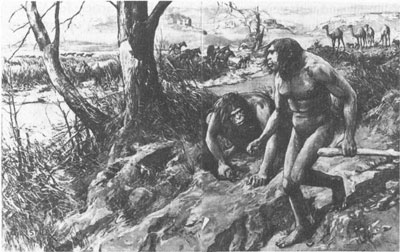

The infamous restoration of

Hesperopithecus

published in the

Illustrated London News

in 1922.

NEG. NO. 2A17487. COURTESY DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SERVICES, AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

.

Forestier’s figure is the one ridiculed and reproduced by creationists, and who can blame them? The attempt to reconstruct an entire creature from a single tooth is absolute folly—especially in this case when the authors of

Hesperopithecus

had declined to decide whether their creature was ape or human. Osborn had explicitly warned against such an attempt by pointing out how organs evolve at different rates, and how teeth of one type can be found in bodies of a different form. (Ironically, he cited Piltdown as an example of this phenomenon, arguing that, by teeth alone, the “man” would have been called an ape. How prescient in retrospect, since Piltdown is a fraud made of orangutan teeth and a human skull.)

Thus, Osborn explicitly repudiated the major debating point continually raised by modern creationists—the nonsense of reconstructing an entire creature from a single tooth. He said so obliquely and with gentle satire in his technical article for

Nature

, complaining that G. E. Smith had shown “too great optimism in his most interesting newspaper and magazine articles on

Hesperopithecus

.” The

New York Times

reported a more direct quotation: “Such a drawing or ‘reconstruction’ would doubtless be only a figment of the imagination of no scientific value, and undoubtedly inaccurate.”

Among the smaller number of allowable points, I can hardly blame creationists for gloating over the propaganda value of this story, especially since Osborn had so shamelessly used the original report to tweak Bryan. Tit for tat.

I can specify only one possibly legitimate point of criticism against Osborn and Gregory. Perhaps they were hasty. Perhaps they should have waited and not published so quickly. Perhaps they should have sent out their later expedition before committing anything to writing, for then the teeth would have been officially identified as peccaries first, last, and always. Perhaps they proceeded too rapidly because they couldn’t resist such a nifty opportunity to score a rhetorical point at Bryan’s expense. I am not bothered by the small sample of only two teeth. Single teeth, when well preserved, can be absolutely diagnostic of a broad taxonomic group. The argument for caution lay in the worn and eroded character of both premolars. Matthew had left the second tooth of 1908 in a museum drawer; why hadn’t Osborn shown similar restraint?

But look at the case from a different angle. The resolution of

Hesperopithecus

may have been personally embarrassing for Osborn and Gregory, but the denouement was only invigorating and positive for the institution of science. A puzzle had been noted and swiftly solved, though not in the manner anticipated by the original authors. In fact, I would argue that Osborn’s decision to publish, however poor his evidence and tentative his conclusions, was the most positive step he could have taken to secure a resolution. The published descriptions were properly cautious and noncommittal. They focused attention on the specimens, provided a series of good illustrations and measurements, provoked a rash of hypotheses for interpretation, and inspired the subsequent study and collection that soon resolved the issue. If Osborn had left the molar in a museum drawer, as Matthew had for the second tooth found in 1908, persistent anomaly would have been the only outcome. Conjecture and refutation is a chancy game with more losers than winners.

I have used the word

irony

too may times in this essay, for the story of

Hesperopithecus

is awash in this quintessential consequence of human foibles. But I must beg your indulgence for one last round. As their major pitch, modern fundamentalists argue that their brand of biblical literalism represents a genuine discipline called “scientific creationism.” They use the case of Nebraska Man, in their rhetorical version, to bolster this claim, by arguing that conventional science is too foolish to merit the name and that the torch should pass to them.

As the greatest irony of all, they could use the story of

Hesperopithecus

, if they understood it properly, to advance their general argument. Instead, they focus on their usual ridicule and rhetoric, thereby showing their true stripes even more clearly. The real message of

Hesperopithecus

proclaims that science moves forward by admitting and correcting its errors. If creationists really wanted to ape the procedures of science, they would take this theme to heart. They would hold up their most ballyhooed, and now most thoroughly discredited, empirical claim—the coexistence of dinosaur and human footprints in the Paluxy Creek beds near Dallas—and publicly announce their error and its welcome correction. (The supposed human footprints turn out to be either random depressions in the hummocky limestone surface or partial dinosaur heel prints that vaguely resemble a human foot when the dinosaur toe strikes are not preserved.) But the world of creationists is too imbued with irrefutable dogma, and they don’t seem able even to grasp enough about science to put up a good show in imitation.

I can hardly expect them to seek advice from me. May they, therefore, learn the virtue of admitting error from their favorite source of authority, a work so full of moral wisdom and intellectual value that such a theme of basic honesty must win special prominence. I remind my adversaries, in the wonderful mixed metaphors of Proverbs (25:11,14), that “a word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in pictures of silver…. Whoso boasteth himself of a false gift is like clouds and wind without rain.”

CHARLES LYELL

, defending both his version of geology and his designation of James Hutton as its intellectual father, described Richard Kirwan as a man “who possessed much greater authority in the scientific world than he was entitled by his talents to enjoy.”

Kirwan, chemist, mineralogist, and president of the Royal Academy of Dublin, did not incur Lyell’s wrath for a mere scientific disagreement, but for saddling Hutton with the most serious indictment of all—atheism and impiety. Kirwan based his accusations on the unlikely charge that Hutton had placed the earth’s origin beyond the domain of what science could consider or (in a stronger claim) had even denied that a point of origin could be inferred at all. Kirwan wrote in 1799:

Recent experience has shown that the obscurity in which the philosophical knowledge of this [original] state has hitherto been involved, has proved too favorable to the structure of various systems of atheism or infidelity, as these have been in their turn to turbulence and immorality, not to endeavor to dispel it by all the lights which modern geological researches have struck out. Thus it will be found that geology naturally ripens…into religion, as this does into morality.

In our more secular age, we may fail to grasp the incendiary character of such a charge at the end of the eighteenth century, when intellectual respectability in Britain absolutely demanded an affirmation of religious fealty, and when fear of spreading revolution from France and America equated any departure from orthodoxy with encouragement of social anarchy. Calling someone an atheist in those best and worst of all times invited the same predictable reaction as asking Cyrano how many sparrows had perched up there or standing up in a Boston bar and announcing that DiMaggio was a better hitter than Williams.

Thus, Hutton’s champions leaped to his defense, first his contemporary and Boswell, John Playfair, who wrote (in 1802) that

such poisoned weapons as he [Kirwan] was preparing to use, are hardly ever allowable in scientific contest, as having a less direct tendency to overthrow the system, than to hurt the person of an adversary, and to wound, perhaps incurably, his mind, his reputation, or his peace.

Thirty years later, Charles Lyell was still fuming:

We cannot estimate the malevolence of such a persecution, by the pain which similar insinuations might now inflict; for although charges of infidelity and atheism must always be odious, they were injurious in the extreme at that moment of political excitement [

Principles of Geology

, 1830].

(Indeed, Kirwan noted that his book had been ready for the printers in 1798 but had been delayed for a year by “the confusion arising from the rebellion then raging in Ireland”—the great Irish peasant revolt of 1798, squelched by Viscount Castlereagh, uncle of Darwin’s Captain FitzRoy [see Essay 1 for much more on Castlereagh].)

Kirwan’s accusation centered upon the last sentence of Hutton’s

Theory of the Earth

(original version of 1788)—the most famous words ever written by a geologist (quoted in all textbooks, and often emblazoned on the coffee mugs and T-shirts of my colleagues):

The result, therefore, of our present enquiry is, that we find no vestige of a beginning—no prospect of an end.

Kirwan interpreted both this motto, and Hutton’s entire argument, as a claim for the earth’s eternity (or at least as a statement of necessary agnosticism about the nature of its origin). But if the earth be eternal, then God did not make it. And if we need no God to fashion our planet, then do we need him at all? Even the weaker version of Hutton as agnostic about the earth’s origin supported a charge of atheism in Kirwan’s view—for if we cannot know that God made the earth at a certain time, then biblical authority is dethroned, and we must wallow in uncertainty about the one matter that demands our total confidence.

It is, I suppose, a testimony to human carelessness and to our tendency to substitute quips for analysis that so many key phrases, the mottoes of our social mythology, have standard interpretations quite contrary to their intended meanings. Kirwan’s reading has prevailed. Most geologists still think that Hutton was advocating an earth of unlimited duration—though we now view such a claim as heroic rather than impious.

Yet Kirwan’s charge was more than merely vicious—it was dead wrong. Moreover, in understanding why Kirwan erred (and why we still do), and in recovering what Hutton really meant, we illustrate perhaps the most important principle that we can state about science as a way of knowing. Our failure to grasp the principle underlies much public misperception about science. In particular, Justice Scalia’s recent dissent in the Louisiana “creation science” case rests upon this error in discussing the character of evolutionary arguments. We all rejoiced when the Supreme Court ended a long episode in American history and voided the last law that would have forced teachers to “balance” instruction in evolution with fundamentalist biblical literalism masquerading under the oxymoron “creation science.” I now add a tiny hurrah in postscript by pointing out that the dissenting argument rests, in large part, upon a misunderstanding of science.

Hutton replied to Kirwan’s original attack by expanding his 1788 treatise into a cumbersome work,

The Theory of the Earth

(1795). With forty-page quotations in French and repetitive, involuted justifications, Hutton’s new work condemned his theory to unreadability. Fortunately, his friend John Playfair, a mathematician and outstanding prose stylist, composed the most elegant pony ever written and published his

Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth

in 1802. Playfair presents a two-part refutation for Kirwan’s charge of atheism.

1. Hutton neither argued for the earth’s eternity nor claimed that we could say nothing about its origin. In his greatest contribution, Hutton tried to develop a cyclical theory for the history of the earth’s surface, a notion to match the Newtonian vision of continuous planetary revolution about the sun. The materials of the earth’s surface, he argued, passed through a cycle of perfect repetition in broad scale. Consider the three major stages. First, mountains erode and their products are accumulated as thick sequences of layered sediments in the ocean. Second, sediments consolidate and their weight melts the lower layers, forming magmas. Third, the pressure of these magmas forces the sediments up to form new mountains (with solidified magmas at their core), while the old, eroded continents become new ocean basins. The cycle then starts again as mountains (at the site of old oceans) shed their sediments into ocean basins (at the site of old continents). Land and sea change positions in an endless dance, but the earth itself remains fundamentally the same. Playfair writes:

It is the peculiar excellence of this theory…that it makes the decay of one part subservient to the restoration of another, and gives stability to the whole, not by perpetuating individuals, but by reproducing them in succession.

We can easily grasp the revolutionary nature of this theory for concepts of time. Most previous geologies had envisioned an earth of short duration, moving in a single irreversible direction, as its original mountains eroded into the sea. By supplying a “concept of repair” in his view of magmas as uplifting forces, Hutton burst the strictures of time. No more did continents erode once into oblivion; they could form anew from the products of their own decay and the earth could cycle on and on.

This cyclical theory has engendered the false view that Hutton considered the earth eternal. True, the mechanics of the cycle provide no insight into beginnings or endings, for laws of the cycle can only produce a continuous repetition and therefore contain no notion of birth, death, or even of aging. But this conclusion only specifies that laws of nature’s

present order

cannot specify beginnings or ends. Beginnings and ends may exist—in fact, Hutton considered a concept of starts and stops absolutely essential for any rational understanding—but we cannot learn anything about this vital subject from nature’s present laws. Hutton, who was a devoted theist despite Kirwan’s charge, argued that God had made a beginning, and would ordain an end, by summoning forces outside the current order of nature. For the stable period between, he had ordained laws that impart no directionality and therefore permit no insight into beginnings and ends.

Note how carefully Hutton chose the words of his celebrated motto. “No

vestige

of a beginning” because the earth has been through so many cycles since then that all traces of an original state have vanished. But the earth certainly had an original state. “No

prospect

of an end” because the current laws of nature provide no insight into a termination that must surely occur. Playfair describes Hutton’s view of God:

He may put an end, as he no doubt gave a beginning, to the present system, at some determinate period; but we may safely conclude, that this great catastrophe will not be brought about by any of the laws now existing, and that it is not indicated by any thing which we perceive.

2. Hutton did not view our inability to specify beginnings and ends as a baleful limitation of science but as a powerful affirmation of proper scientific methodology. Let theology deal with ultimate origins, and let science be the art of the empirically soluble.

The British tradition of speculative geology—from Burnet, Whiston, and Woodward in the late seventeenth century to Kirwan himself at the tail end of the eighteenth—had focused upon reconstructions of the earth’s origin, primarily to justify the Mosaic narrative as scientifically plausible. Hutton argued that such attempts could not qualify as proper science, for they could only produce speculations about a distant past devoid of evidence to test any assertion (no vestige of a beginning). The subject of origins may be vital and fascinating, far more compelling than the humdrum of quotidian forces that drive the present cycle of uplift, erosion, deposition, and consolidation. But science is not speculation about unattainable ultimates; it is a way of knowing based upon laws now in operation and results subject to observation and inference. We acknowledge limits in order to proceed with power and confidence.

Hutton therefore attacked the old tradition of speculation about the earth’s origin as an exercise in futile unprovability. Better to focus upon what we can know and test, leaving aside what the methods of science cannot touch, however fascinating the subject. Playfair stresses this theme more forcefully (and more often) than any other in his exposition of Hutton’s theory. He regards Hutton’s treatise as, above all, an elegant statement of proper scientific methodology—and he locates Hutton’s wisdom primarily in his friend’s decision to eschew the subject of ultimate origins and to focus on the earth’s present operation. Playfair begins by criticizing the old manner of theorizing:

The sole object of such theories has hitherto been, to explain the manner in which the present laws of the mineral kingdom were first established, or began to exist, without treating of the manner in which they now proceed.

He then evaluates this puerile strategy in one of his best prose flourishes:

The absurdity of such an undertaking admits of no apology; and the smile which it might excite, if addressed merely to the fancy, gives place to indignation when it assumes the air of philosophic investigation.

Hutton, on the other hand, established the basis of a proper geological science by avoiding subjects “altogether beyond the limits of philosophical investigation.” Hutton’s explorations “never extended to the first origin of substances, but were confined entirely to their changes.” Playfair elaborated:

He has indeed no where treated of the first origin of any of the earths, or of any substance whatsoever, but only of the transformations which bodies have undergone since the present laws of nature were established. He considered this last as all that a science, built on experiment and observation, can possibly extend to; and willingly left, to more presumptuous inquirers, the task of carrying their reasonings beyond the boundaries of nature.

Finally, to Kirwan’s charge that Hutton had limited science by his “evasion” of origins, Playfair responded that his friend had strengthened science by his positive program of studying what could be resolved:

Instead of an

evasion

, therefore, any one who considers the subject fairly, will see, in Dr. Hutton’s reasoning, nothing but the caution of a philosopher, who wisely confines his theory within the same limits by which nature has confined his experience and observation.

This all happened a long time ago, and in a context foreign to our concerns. But Hutton’s methodological wisdom, and Playfair’s eloquent warning, could not be more relevant today—for basic principles of empirical science have an underlying generality that transcends time. Practicing scientists have largely (but not always) imbibed Hutton’s wisdom about restricting inquiry to questions that can be answered. But Kirwan’s error of equating the best in science with the biggest questions about ultimate meanings continues to be the most common of popular misunderstandings.

I have written these monthly essays for nearly twenty years, and they have brought me an enormous correspondence from non-professionals about all aspects of science. From sheer volume, I obtain a pretty good sense of strengths and weaknesses in public perceptions. I have found that one common misconception surpasses all others. People will write, telling me that they have developed a revolutionary theory, one that will expand the boundaries of science. These theories, usually described in several pages of single-spaced typescript, are speculations about the deepest ultimate questions we can ask—what is the nature of life? the origin of the universe? the beginning of time?

But thoughts are cheap. Any person of intelligence can devise his half dozen before breakfast. Scientists can also spin out ideas about ultimates. We don’t (or, rather, we confine them to our private thoughts) because we cannot devise ways to test them, to decide whether they are right or wrong. What good to science is a lovely idea that cannot, as a matter of principle, ever be affirmed or denied?