Burning : A Tale of the Dark Apostle (9780698144743) (2 page)

Read Burning : A Tale of the Dark Apostle (9780698144743) Online

Authors: E.c. Ambrose

I turned, my heart thundering in fear of finding Owain already there, but it was Father John filling the door. “You're coming with me, Elisha, to take care of that Devil once and for all.”

Elisha shook his head. He glanced at me and caught sight of his things bundled in my arms. “It was no Devilâthere was no Devil that touched me, Father, you've got to believe me.”

“The Devil sends visions to overpower the weak. He spreads his poison through his witches here on earth, and even through the innocents they snare. If your soul is pure, boy, you have nothing to fear.”

“Don't send me away, Mum.”

My heart near melted, but I clasped the wooden cross I wore and said, “It's for your soul, Elisha. There's naught else to do.”

Father John loomed there in the door, hands spread in pleading for my son's faith.

“No!” Elisha shouted. “The Devil take youâhe's never had me!”

In that awful moment, while we crossed ourselves and the priest started forward, Elisha made a run for the door. Father John snatched him up. He bound Elisha's wrists, then had to gag him so he wouldn't call back his father with screaming. Tears streamed down my cheeks, and my son'sâbut after that awful curse, I could only pray it wasn't already too late.

Father John put Elisha upon the saddle before him and mounted his tall horse. I offered up the bundle, but the boy struggled so that the priest had to hang onto him with one hand while he steered his mount with the other. “God be with you, Edith!” Father John shouted, but the clouds of his worries crowded out any compassion this time. They galloped away toward the mill bridge and the Roman road beyond. I wiped my face on my sleeve, clutching Elisha's things to my chest. Foolish womanâhe'd be given a habit there, given all he needed, as well as what we could not provide: a sanctuary against the fiend. The road climbed up the hill, and I watched until they topped it and disappeared over the other side toward the water before I finally turned away.

Tucking the bundle under our bed, I laid out the boys' mattresses of straw along the wall, then stopped myself, and stacked them instead. Nathaniel might as well have a little more comfort. He'd need that tonight when he knew his brother was gone. I heard him and Owain talking as they came up to the door, then Owain called my name.

Fixing my face with a plain expression I went out and got a shock to realize I hadn't put the colt away, but left him by the post, I'd been so anxious about getting inside to keep an eye on Elisha.

“Why's the horse here? Elisha!” Owain slid Nathaniel down from his shoulders, and tousled his hair.

“Oh, he's tending the sheep. I'll take care of it.” I reached for the reins, but Owain caught my arm.

“Don't lie to me, woman. I can feel a lie.” He bared his teeth, his fingers too tight. “Where's Elisha?”

I stood my ground. “I asked Father John to come for him. To take him to the abbey where he can be brought back to God.”

Owain cried out and pushed me away. At that sound, Nathaniel grabbed my skirts, staring up at his father.

“But the priest was lying! I know he was lying!”

“What about, Owain? You're not making any sense. You tell me you're in torment, but you won't trust the priest. You're afraid for our son, but you don't care that our neighbors want him dunked! You won't let the priest tend to his soulâI don't know who you are any more!”

Then he stood for a moment and he spoke softly. “I'm sorry you don't know who I am,” he told me. “I'm sorry that you never did.” He seized the reins and flung himself up to the colt's back. “Where did they go?”

He looked majestic, just then, his hair made bright in the last of the sun, his face made terrible by the secrets he held from me.

“Edithâwhere?” he barked down at me. In the brightness of the sunset, he burned. The priest was lying, my husband was afraid, and the priest had taken our son down the mill bridge road.

I shook off Nathaniel's hands. “Stay here!” Then I pulled myself up behind Owain, wrapping an arm about his chest, my hand pressed against his heart. “There! To the bridge!”

With a hard kick to the colt's ribs, Owain thundered down the path.

“Tell me!” I shouted into the wind.

Owain's fingers found mine and twined into them. “You'll curse me, Edith, as you are a God-fearing woman, you'll wish me dead.”

“No,” I told him, but my voice shook, and I clung to him tighter, my face pressed against his strong back. What could be so awful that it tormented my husband and spread to my son? “You're a witch,” I breathed, as the wind whipped the tears from my face.

He could not have heard me, but his chest shuddered with a deep breath beneath our joined hands. “I never meant to be, Edith, and sure I never wanted to taint my son.” He swallowed and spoke again. “I can feel a lie. I can feel the truth. I can feel the minds of the dogs and the horse and the sheep. I can feel when springtime's moving in the ground.” He jerked another breath. “I can feel you love me. I can feel your fear.”

He was right, God help me, about the fear and the love. “I thought I was losing youâthat keeping Elisha meant losing you both.”

“To Satan?” He gave a sharp laugh. “For me, at least, it's too late.”

“It can't be,” I wailed, but his words struck cold through my body. A man could have uncanny ways, he could know animals and lies and not be a witch, couldn't he? Owain was no witch, only wise to the ways of man and beast, but another man might not see that. Another manâeven a priestâmight see witchcraft, and worry over that man's son. “Faster!”

Owain bent forward, and that colt gave his heart. I squeezed my eyes to shut out the way the hedges blew past as we rode. Up the hill and down the other side, and the colt stumbled. I rolled off his back, and Owain dropped heavily, catching the colt's head and murmuring so its wild eyes went calm. The rumble of the millstream filled my ears, along with a splashing. Bunching my skirts in my hands I ran, leaving the tall shadow of the mill. Father John's horse towered in the center of the bridge, the priest staring into the water where violent ripples spread.

His head jerked up when he saw me and he kicked his horse into motion, clattering to come before me, the horse's hooves splashing in the pond.

“Elisha!” I shouted.

“Wait!” Father John cried, opening his hand before me, his face grave. “Wait and see if he rises.”

“And if he sinks, he dies!” I tried to get around him, but the priest drove his horse again before me. “He can't swim!”

Owain's voice rumbled, “No more can you.” My husband seized my arm and thrust me behind.

“Would you not rather your son reside with the Lord in Heaven than be possessed of the Devil here below?”

My husband raised his chin. “That is for God, not you, to say.” Then Owain ripped apart the air with his hands and howled, “Be gone!”

Father John's horse pranced and skittered, drenching us both as it cleared his path.

At my husband's command, the waters rose.

They tore before him as if his hands had gripped the waters and severed them each from each. Rippling in the sunset, the pond broke in two, pushed away to either side, furrowed as the earth by a plow. At our feet, slick green stones appeared and pebbles and pilgrim's tin badges tossed in to bless the village. A few fish flopped in the air as the waters departed. Others flashed tail or fins in the gleaming walls. Sticks protruded and receded, bobbing still above sunken stumps andâthere!

Elisha lay drenched, face down in the mud.

I stumbled past Owain, slipping on stones, tripping over roots, squelching and losing a shoe before I caught Elisha's cold shoulder and pulled him from the muck. I rolled him into my arms, wiping his face, pulling free the gag. His chest shuddered and his legs twitched as I drew him close, and rose. His feet broke the water wall, splashing and startling the fish.

To either side, water rose above our heads, higher than our house, higher than our apple trees, a dark passage back to the earth, which still glowed gold before us. Owain stood there, feet braced, hands spread, eyes wide and unbelieving.

“Unholy fiend!” Father John wheeled his horse back, plunging into the chasm Owain held, but the horse would not run my husband down. It brushed his hand, and he shook his head, just a little.

The horse shied, rearing, trying to turn away from Owain. Father John shrieked as he fell.

“Run!” Owain told me, and his arms trembled.

I stumbled toward shore, Elisha cradled in my arms. I skidded once and fell on my back, but the jolt popped Elisha's eyes open. He coughed violently, his thin frame rocking with it as I tightened my grip and ran once more.

“Edith! Do you not see the Devil's work here?” Father John slithered to his knees, his hand reaching toward me as I ran by.

I lay my son by the bridge and turned back. The priest staggered to his feet, swaying, his hand impossibly large. Noâa stone. He swung hard, his teeth set into fury.

The cracking of my husband's skull echoed in the dusk. He fell, face downward, the walls of water crashing in upon him. Upon them both.

Father John broke the surface, sputtering, waving an arm, bobbing like the Devil's thing, but Owain never rose again.

“Mum.” Elisha's voice, weak and small as never before. He coughed again, wiping his face on his quaking shoulder.

I found breath and went to him, tugging at the rag until his hands came free. “We have to leave, now, tonight. The colt's gone lameâyou'll need to walk with him.”

“Where's Da? I thought I heard him.”

Where indeed? Heaven, for he stayed beneath the waters? Or Hell for how they took him? Hell for the priest that drowned beside him, or Heaven, for saving his son? “I don't know.”

“Don't lie to me, Mum,” Elisha whispered. “I can feel it.”

Only once I struck that boy, and we never spoke of it again. His father saved his body, and still, I fought for his soul.

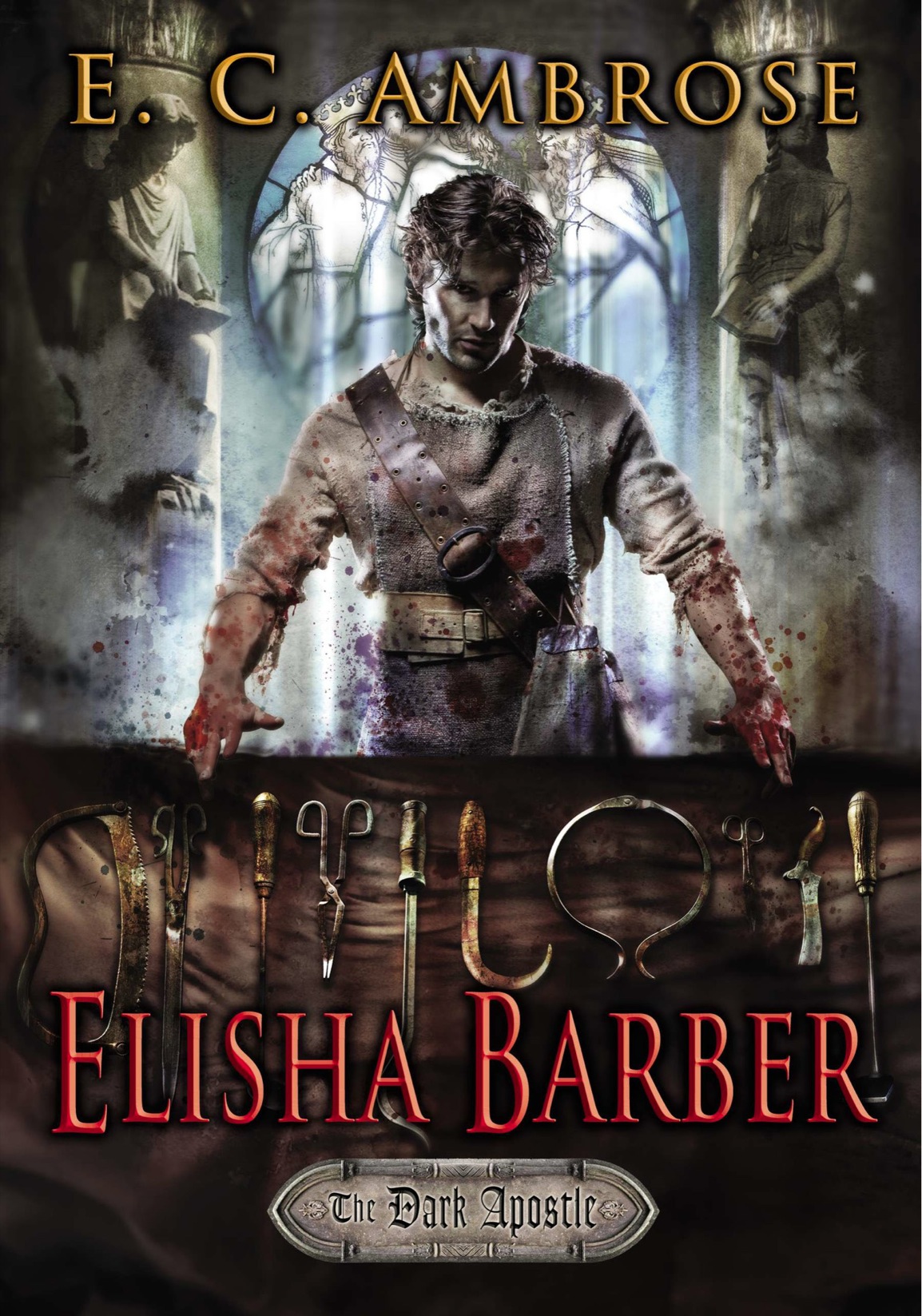

ELISHA BARBER

, AVAILABLE FROM DAW BOOKS JULY 2, 2013.

Elisha had witnessed magic once, when he was yet a boy, the last time a witch had been brought to trial. This was before even the terrible drought which had forced his family into the city to find work. His parents came in from the country to watch the execution, packing lunch for all of them, plus a few leftover vegetables from the garden gone soft and rotten, ripe for the throwing. Nathaniel, judged too young over his protests to the contrary, had been left at a neighbor's house to sulk.

The three of them rode in their pony cart, the rangy new colt drawing them onward with the press of country folk all out in a common purpose. A tall pole had been erected outside the city wall in a patch of barren ground. The vivid purple of the royal pavilion, where the king and his two sons could recline in comfort for the festivities, brightened the gray of the city wall. Elisha had never been so close to the royal family, before or since. Nobility and townsfolk occupied the ground nearest to the site, leaving some distance for safety, so that the country farmers took up the surrounding grass, paying a few pennies to stand atop wagon seats for a better view.

Vendors wandered the makeshift rows, hawking all manner of sweets and ale from barrels slung upon their backs. Musicians roamed as well, offering songs for the ladies, while a handful of bards tossed off poems with quick wit.

Elisha begged a penny from his father to buy a little pennant of cloth painted with a hawk. So equipped, he ran about the grass, watching it flutter in the breeze. Dashing down a long slope, he stopped short.

Heedless of the direction he'd run, the boy found himself surrounded by fine carriages and ladies seated beneath stretched fabric to avoid the sun. He'd just begun to squint into the distance, searching for his parents, when the crowd around him fell silent, then let out a roar. Or so he thought until he turned around.

Elisha stood in the second rank of witnesses, not ten yards from the stake. Around him stood the king's archers, keeping a watchful eye for rioters, not caring for a wandering child. From their distant rise, Elisha's family could make out little but the pillar and its mound of wood. Close-to, he saw the woman bound there, clad in white, the pale ropes wound all about her.

Her hands writhed against the bindings, and her lips moved faintly. They had shorn her hair, leaving only a rough fringe of red, revealing her terrified face.

The roar came not from the people gathered round but from a crimson flame licking the piled wood at the woman's feet.

Elisha's mouth hung open, and he shut it with a snap, his mother's scold sounding inside his head.

As the flames drew ever nearer to the woman's bare feet, the movement of her lips became fierce, until she let out a shriek that deafened him for an instant. Then the crowd roared indeed, chanting for her death. Smoke swirled around him, choking him and stinging his eyes. He rubbed them, reluctant to miss any of the spectacle. And it was then that the miracle happened.

Even as he stared, making out the woman's form within the growing flames, she seemed to sway and stretch. Then as she howled, her back bent, and the first bond broke. From both shoulders, the fabric strained, then tore. Golden and enormous, a pair of wings stretched out behind her, dwarfing her in their embrace.

Their first powerful sweep knocked Elisha down and blasted the shades around him, tearing at the ladies' hair, sending one pavilion crashing to the ground as the tethered horses bucked and ran. Nobles screamed and called out prayers. The priests scrambled back to their feet, thrusting up crosses and shouting into the wind.

Fighting that wind, Elisha rose. The sweep of her wings blew back his hair.

She glowed from head to foot, from wingtip to wingtip, the feathers glistening in the air. Even among the saints and virgins of church frescoes, he had never seen anything so beautiful. Elisha felt sure their eyes met. Her luminous eyes reflecting the flames that spat around her as she struggled to rise, then widening in agony as the first arrow struck. Blood spattered the golden wings.

Arrows tore into her feathers and slammed into flesh, piercing her legs and breast and throat.

Screaming, Elisha ran toward the fire. If he could only reach her, he could stop the bleeding, cut the ropes and set her free. Had the smoke so blinded them that they could not see she had transformed into an angel?

A priest snatched him by the shoulder, clinging despite the boy's resistance. Still, he had come close enough to be struck first by the heat, then by the tip of one powerful wing as they beat their last and vanished.

The witch's body bent into the flames, all life gone from her long before her body was consumed.

Panting, Elisha stood still, watching the flames, one hand pressed to his cheek where the angel's wing had stroked his skin.

Even now, twenty years later, that soft, delicious touch lingered in his flesh. For the first time, he wondered if he had avoided love because of that angel, because their eyes had met through a wall of flame.

His fingers traced a line across his cheek.

Too far away to see the truth, his parents thought the flames had gone out of control. When the priest returned their child, they were relieved he had not been harmed. Rumors abounded that the witch had worked some final curse upon those nearest, and Elisha was baptized again and made to attend a week of special services to rid him of whatever evil residue she had left behind. For a time, they all acted as if he had absorbed some witchcraft. His father beat him twice as hard, and four times as often, to re-instill the proper discipline, and Elisha allowed himself to be convinced that the angel had been a trick, a perversion of God's seraphim meant to ensnare the minds of the weak-willed and the children. But as the memory of prayers and beatings receded, the angel's touch remained.

After they moved to the city, he'd found a barber in need of an apprentice. He learned well enough how to cut hair, pull teeth, and bleed patients on the orders of their doctors, but he quickly surpassed his master in his eagerness to learn the ways of surgery. If ever he had the chance to bind an angel's wounds, Elisha would be ready.

He laughed at himself in the darkness, fingering the strap of his leather bag. For twenty years that memory seemed too secret to share even with his conscious thoughts. As an adult, he had never spoken of it to anyone, though he heard the occasional reference muttered in a tavern or whispered in the church. Certainly he never sought out the company of witches, not that there were any to find in these parts after that day. The few who had been hunted down since were quietly dispatched with sword or arrow lest they cast another such glamour upon an audience so vast.

Considering this, he finally stood, took up the satchel and the dreadful weight within it, and gathered his tools from the table. The Bone of Luz, that mystical seed from which he might grow a new man, should be a thing of anatomy, yet he had not seen it nor heard of any who had. Still, even Lucius Physician professed his belief, and he had studied at Salerno. Church law forbade dissection, except where required for criminal investigation, but Elisha's work had introduced him to most of the bones and organs of the body. Where might the Bone lie, then? Not the abdomen, surely, where it might obstruct the body's courses. Legend placed it at the top of the spine, but wouldn't those martyrs beheaded then be denied their resurrection? He guessed it would be found in the skull, the sanctum of a man's intellect, and perhaps his soul. Trepanation was not Elisha's specialty. Despite his experience, the thought of punching a hole in someone's head, even to cure him of worse ills, worried him greatly. The Bone, if it did exist, must reside somewhere behind the eyes.

Snuffing the lamp, Elisha shut the door behind him and picked his way in the dark to the back of the house and his own chambers. There was still the packing to doâselecting the best and most needed of his tools and medicaments, the rest to be left to Helena's disposal. Before he began that, however, he located certain salts and herbs and a squat, lidded pot recently emptied of weapons ointment and suited to his needs. In the alley behind the house stood the pump and cistern. On its stone overflow rim, he set down the satchel and gently searched its contents until he found the infant's small, soft head. In the terrible operation he had performed, most surgeons would have crushed the little skull to let it pass more easily. Thankfully, he had not needed that final barbarity today. Placing it into the pot, he covered it with oils of turpentine and lavender, hoping the Bone within would not be damaged by the preservative mixture.

When that was done, Elisha washed his tools, then himself and his bloody clothes, splashing cold water by the bucket over his body. He scrubbed his hands until it felt that he would bring forth blood of his own, and finally returned to his study with his burdens, shivering in the growing chill of night. He sealed the lid of his little pot with wax and thrust it to the bottom of a small chest. He found fresh clothes, draping his wet things to dry for the morrow.

Elisha sat a long time with the sorry satchel before him. He knew what must be done, but the tools would be in his brother's workshop, and the thought of going inside, facing that absence, made him feel heavy as stone. Still, he could not leave Helena to face her child's remainsâor risk someone knowing what he had taken. Someday, he might return to her in triumph, restoring the baby he had cost her. Her husband was a loss for which he could not make amends.

Not far off, the church bells rang, and Elisha stirred himself to motion. He had little enough time as it was. He took up the satchel and went to the workshop. He almost knocked, but his lifted hand paused in time. No amount of knocking would rouse the dead. He pushed gently and went inside. It took a moment for his eyes to adjustâa long moment in which the shadows formed his brother's corpse. But no, the place was empty, Nathaniel's body taken away to prepare for burial, his blood merely darker shadows on the earthen floor.

Nate always started work early, and Elisha used to pause in the yard to listen to the rhythm of hammer and files. Once, he caught his brother singing while he worked and made some remark, hoping to touch him beyond the rift he had caused, but Nathaniel turned from him and sang no more.

Elisha's eyes burned with sudden tears. He forced himself to look away, forced himself to move to the neat racks of tools and find the spade for turning the coals in the hearth. On a narrow bench by the windowsill waited a row of little crosses Nate would have sold at fairs or to his other customers. Elisha took one of these, the shape pressing into his palm beneath the handle of the spade. If it should carve straight through him it would not be punishment enough.

He made his way through the narrow streets, giving a few coins to the guard at Cripplegate to let him pass. Beyond the wall, and a few more turns, Saint Bartholomew's churchyard lay before him, humped with graves. He wished he knew where his brother would lie, so he could place the child close by. Failing that, he found a place that looked too narrow for an adult's grave, not far from the church's tower. The monastic hospital rose a short way off, founded by a king's fool two centuries ago, along with the church itself. A man would have to be a fool to place his trust in either God or doctors. His brother had been failed by both.

Using the short-handled spade, awkward in his hands, Elisha peeled back the layer of grass and dug as deep as he might. He nestled the satchel into the hole, dark into darkness, and bowed his head. There should be prayers for this. On a better day, he might recall them. He wet his lips and searched for words, his hands pressed together before him. “Dear Lord,” he started, and a lump rose in his throat. He stared down into the dark hole where his brother's child lay. God was too far away to hear anything Elisha might say.

To the child, he whispered, “Forgive me.” His fingers knotted together and his shoulders shook, but he felt no answer. “I swear I will take care of you.” He was the elder; his care was what Nathaniel should have had. He tried, hadn't he? He didn't want Helena for himself, he wanted to show Nathaniel what he thought she was, to protect him. But Elisha was wrong. He wronged his brother, he wronged his brother's wife. He became a barber to heal others, but instead he wounded them unto death.

Softly, ever so softly, as if the other graves could hear him speak, he said, “If I can, I'll see you born again. If not, if there is life in me, I'll see your spirit laid to rest.”

He drew back and began to fill the little grave, pressing the grass back over it. Tomorrow he would go to war. He deserved death for the terrible day his deeds had brought, but he hoped for life. He hoped for a penance so great, a labor so severe that these dead might be appeased.

Last, he found the cross his brother made. Crosses of wood and carved stones marked the graves around him, some with words he knew to be the names of the dead, with their dates of birth and death, dates that bounded lives both long and short. April fifth, the Year of Our Lord, 1347. This child had not a year, not a month, not even a single day. If they had spoken of names for their baby in the darkness of their bed, Elisha did not know it. He pushed the end of the cross, empty of mark or word, into the grass and brushed the dirt from his hands before he crossed himself.

“I'm sorry,” he whispered through his tears, his hands clutched together, begging. “I am so sorry.” He squeezed his eyes shut, his throat burning, until the tears receded, and he thought he could rise without stumbling.

With the spade alone to fill his hands, Elisha walked away through the shadowed streets.

Back in his room, silence echoing overhead, Elisha set to work on his traveling chest. All around and over the dangerous jar, he packed envelopes and vialsâmelon seeds, slippery elm, cochineal, thistle leavesâthen sat back and stared at the motley collection.

“I'm not a damned apothecary,” he muttered. No doubt the physician had gotten several apothecaries already, and of more use than Elisha's mere general knowledge. And the great man himself would have a store of expensive medicines: nutmeg and cloves, powdered mummy, bezoar stone. Elisha unpacked most of the herbs and put them aside in favor of a few more instruments, a larger amputating saw, a silver crow's beak for clamping veins, a selection of probes and lances. All of his needles he added to the chest, and the rolls of suturing thread. A few ewers and bowls for bloodletting settled on top, with a smaller basin and a spare razor. These last he hesitated over, imagining Nathaniel lying beside his best basin. That one he could not bring himself to use again, no matter its value. Let Helena sell it off.