Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (17 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

“I interpreted to the chiefs,” George Bent said afterward, “and Red Cloud replied if the whites would go clear out of his country and make no roads it was all right. Dull Knife said the same for the Cheyennes; then both chiefs said for the officer [Williford] to take the train due west from this place, then turn north and when he had passed the Bighorn Mountains he would be out of their country.”

4

Sawyers again protested. To follow such a route would take him too far out of his way; he said he wanted to move north along the Powder River valley to find a fort that General Connor was building there.

This was the first news that Red Cloud and Dull Knife had heard of General Connor and his invasion. They expressed surprise and anger that soldiers would dare build a fort in the heart of their hunting grounds. Seeing that the chiefs were growing hostile, Sawyers quickly offered them a wagonload of goods—flour, sugar, coffee, and tobacco. Red Cloud suggested that

gunpowder, shot, and caps be added to the list, but Captain Williford objected strongly; in fact, the military officer was opposed to giving the Indians anything.

Finally the chiefs agreed to accept a full wagonload of flour, sugar, coffee, and tobacco in exchange for granting permission for the train to move to Powder River. “The officer told me,” George Bent later said, “to hold the Indians back away from the train and he would unload the goods on the ground. He wanted to go on to the river and camp. This was at noon. After he reached the river and corralled his train there, another lot of Sioux came up from the village. The wagonload of goods had already been divided by the first party of Indians, so these newcomers demanded more goods, and when the officer refused they began firing on the corral.”

5

This second band of Sioux harassed Sawyers and Williford for several days, but Red Cloud and Dull Knife and their warriors took no part in it. They moved on up the valley to see if there was anything to the rumors of soldiers building a fort on the Powder.

In the meantime, Star Chief Connor had started construction of a stockade about sixty miles south of the Crazy Woman Fork of the Powder and named it in honor of himself, Fort Connor. With Connor’s column was a company of Pawnee scouts under command of Captain Frank North. The Pawnees were old tribal enemies of the Sioux, Cheyennes, and Arapahos, and they had been enlisted for the campaign at regular cavalrymen’s pay. While the soldiers cut logs for Connor’s stockade, the Pawnees scouted the area in search of their enemies. On August 16 they sighted a small party of Cheyennes approaching from the south. With them was Charlie Bent’s mother, Yellow Woman.

She was riding with four men slightly in advance of the main party, and when she first saw the Pawnees on a low hill she thought they were Cheyennes or Sioux. The Pawnees signaled with their blankets that they were friends, and the Cheyennes moved on toward them, suspecting no danger. When the Cheyennes came close to the hill, the Pawnees suddenly attacked them. And so Yellow Woman, who had left William Bent because he was a member of the white race, died at the hands of a mercenary of her own race. On that day her son Charlie was

only a few miles to the east with Dull Knife’s warriors, returning from the siege of Sawyers’ wagon train.

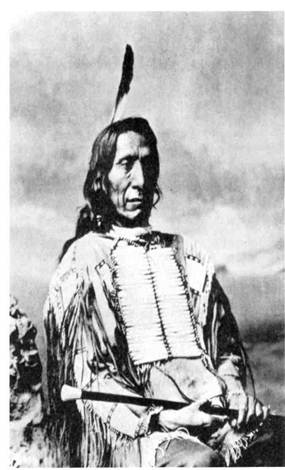

10. Red Cloud, or Mahpiua-luta, of the Oglala Dakotas. Photographed by Charles M. Bell in Washington, D.C., in 1880. Courtesy of the

Smithsonian Institution.

On August 22 General Connor decided that the stockade on the Powder was strong enough to be held by one cavalry company. Leaving most of his supplies there, he started with the remainder of his column on a forced march toward the Tongue River valley in search of any large concentrations of Indian lodges that his scouts might find. Had he moved north along the Powder he would have found thousands of Indians eager for a fight—Red Cloud’s and Dull Knife’s warriors who were out searching for Connor’s soldiers.

About a week after Connor’s column left the Powder, a Cheyenne warrior named Little Horse was traveling across this same country with his wife and young son. Little Horse’s wife was an Arapaho woman, and they were making a summer visit to see her relatives at Black Bear’s Arapaho camp on Tongue River. Along the way one day, a pack on his wife’s horse got loose. When she dismounted to tighten it, she happened to glance back across a ridge. A file of mounted men was coming along the trail far behind them.

“Look over there,” she called to Little Horse.

“They’re soldiers!” Little Horse cried. “Hurry!”

As soon as they were over the next hill, and out of view of the soldiers, they turned off the trail. Little Horse cut loose the travois on which his young son was riding, took the boy on behind him, and they rode fast—straight across country for Black Bear’s camp. They came galloping in, disturbing the peaceful village of 250 lodges pitched on a mesa above the river. The Arapahos were rich in ponies that year; three thousand were corralled along the stream.

None of the Arapahos believed that soldiers could be within hundreds of miles, and when Little Horse’s wife tried to get the crier to warn the people, he said: “Little Horse has made a mistake; he just saw some Indians coming over the trail, and nothing more.” Certain that the horsemen they had seen were soldiers, Little Horse and his wife hurried on to find her relatives. Her brother, Panther, was resting in front of his tepee, and they told him that soldiers were coming and that he had better

move out in a hurry. “Pack up whatever you wish to take along,” Little Horse said. “We must go tonight.”

Panther laughed at his Cheyenne brother-in-law. “You’re always getting frightened and making mistakes about things,” he said. “You saw nothing but some buffalo.”

“Very well,” Little Horse replied, “you need not go unless you want to, but we shall go tonight.” His wife managed to persuade some of her other relatives to pack up, and before nightfall they left the village and moved several miles down the Tongue.

6

Early the next morning, Star Chief Connor’s soldiers attacked the Arapaho camp. By chance, a warrior who had taken one of his race horses out for a run happened to see the troops assembling behind a ridge. He galloped back to camp as fast as he could, giving some of the Arapahos a chance to flee down the river.

A few moments later, at the sound of a bugle and the blast of a howitzer, eighty Pawnee scouts and 250 of Connor’s cavalrymen charged the village from two sides. The Pawnees swerved toward the three thousand ponies which the Arapaho herders were desperately trying to scatter along the river valley. The village, which had been peaceful and quiet a few minutes before, suddenly became a scene of fearful tumult—horses rearing and whinnying, dogs barking, women screaming, children crying, warriors and soldiers yelling and cursing.

The Arapahos tried to form a line of defense to screen the flight of their noncombatants, but in the first rattle of rifle fire some women and children were caught between the warriors and the cavalrymen. “The troops,” said one of Connor’s officers, “killed a warrior, who, falling from his horse, dropped two Indian children he had been carrying. In retreating, the Indians left the children about halfway between the two lines, where they could not be reached by either party.” The children were shot down.

7

“I was in the village in the midst of a hand-to-hand fight with warriors and their squaws,” another officer said, “for many of the female portion of this band did as brave fighting as their savage lords. Unfortunately for the women and children, our

men had no time to direct their aim … squaws and children, as well as warriors, fell among the dead and wounded.”

8

As quickly as they could catch ponies, the Arapahos mounted and began retreating up Wolf Creek, the soldiers pressing after them. With the soldiers was a scout in buckskins, and some of the older Arapahos recognized him as an old acquaintance who had trapped along the Tongue and Powder years before and had married one of their women. They had considered him a friend. Blanket, they called him, Blanket Jim Bridger. Now he was a mercenary like the Pawnees.

For ten miles the Arapahos retreated that day, and when the soldiers’ horses grew tired, the warriors turned on them, using their old trade guns upon the Bluecoats and stinging them with arrows. By early afternoon Black Bear and his warriors pushed Connor’s cavalrymen back to the village, but artillerymen had mounted two howitzers there, and the big-talking guns filled the air with whistling pieces of metal. The Arapahos could go no farther.

While the Arapahos watched from the hills, the soldiers tore down all the lodges in the village and heaped poles, tepee covers, buffalo robes, blankets, furs, and thirty tons of pemmican into great mounds and set fire to them. Everything the Arapahos owned—shelter, clothing, and their winter supply of food—went up in smoke. And then the soldiers and the Pawnees mounted up and went away with the ponies they had captured, a thousand animals, one-third of the tribe’s pony herd.

During the afternoon Little Horse, the Cheyenne who had tried to warn the Arapahos that soldiers were coming, heard the sound of the big guns. As soon as the soldiers left, he and his wife and those of her relatives who had heeded their warning came back into the burned village. They found more than fifty dead Indians. Panther, Little Horse’s brother-in-law, was lying beside a circle of yellowed grass where his lodge had stood that morning. Many others, including Black Bear’s son, were badly wounded and soon would die. The Arapahos had nothing left except the ponies they had saved from capture, a few old guns, their bows and arrows, and the clothing they were wearing when the soldiers charged into the village. This was the Battle of

Tongue River that happened in the Moon When the Geese Shed Their Feathers.

Next morning some of the warriors followed after Connor’s cavalrymen, who were heading north toward the Rosebud. On that same day the Sawyers wagon train, which the Sioux and Cheyennes had besieged two weeks earlier, came rolling through the Arapaho country. Infuriated by the presence of so many intruders, the Indians ambushed soldiers scouting ahead of the train, stampeded cattle in the rear, and picked off an occasional wagon driver. Because they had expended most of their ammunition fighting Connor’s cavalrymen, the Arapahos were not strong enough to surround and attack Sawyers’ wagons. They constantly harassed the goldseekers, however, until they passed out of the Bighorn country into Montana.

Star Chief Connor meanwhile marched on toward the Rosebud, searching hungrily for more Indian villages to destroy. As he neared the rendezvous point on the Rosebud, he sent scouts out in all directions to look for the other two columns of his expedition, the ones led by the Eagle Chiefs, Cole and Walker. No trace could be found of either column, and they were a week overdue. On September 9 Connor ordered Captain North to lead his Pawnees in a forced march to Powder River in hopes of intercepting the columns. On the second day the Pawnee mercenaries ran into a blinding sleet storm, and then two days later they found where Cole and Walker had camped not long before. The ground was covered with dead horses, nine hundred of them. The Pawnees “were overcome with astonishment and wonder at the sight, for they did not know how the animals had come to their deaths. Many of the horses had been shot through the head.”

9

Nearby were charred remains in which they found pieces of metal buckles, stirrups, and rings—the remains of burned saddles and harnesses. Captain North was uncertain what to make of this evidence of a disaster; he immediately turned back toward the Rosebud to report to General Connor.

On August 18 the two columns under Cole and Walker had joined along the Belle Fourche River in the Black Hills. Morale of the two thousand troops was low; they were Civil War

volunteers who felt they should have been discharged when the war ended in April. Before leaving Fort Laramie, soldiers of one of Walker’s Kansas regiments mutinied and would not march out until artillery was trained upon them. By late August rations for the combined columns were so short that they began slaughtering mules for meat. Scurvy broke out among the men. Because of a shortage of grass and water, their mounts grew weaker and weaker. With men and horses in such condition, neither Cole nor Walker had any desire to press a fight with Indians. Their only objective was to reach the Rosebud for the rendezvous with General Connor.

As for the Indians, there were thousands of them in the sacred places of

Paha Sapa

, the Black Hills. It was summer, the time for communing with the Great Spirit, for beseeching his pity and seeking visions. Members of all the tribes were there at the center of the world, singly or in small bands, engaged in these religious ceremonies. They watched the dust streamers of two thousand soldiers and their horses and wagons, and hated them for their desecration of

Paha Sapa

, from where the hoop of the world bent to the four directions. But no war parties were formed, and the Indians kept away from the noisy, dusty column.