Butterfly's Way: Voices From the Haitian Dyaspora in the United States (11 page)

Read Butterfly's Way: Voices From the Haitian Dyaspora in the United States Online

Authors: Edwidge Danticat

Tags: #American Literature - Haitian American Authors, #Literary Collections, #Social Science, #Anthologies (Multiple Authors), #Haitian American Authors, #20th Century, #American Literature, #Poetry, #American Literature - 20th Century, #Caribbean & Latin American, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Literary Criticism, #Haitian Americans, #General, #Fiction

Garry Pierre-Pierre

My wife is white. When I told my friend Rosemonde over lunch that I intended to marry Donna, a petite woman of English, German, and Irish ancestry from Indiana, Rosemonde's jaw dropped as if she'd been hit with a Mike Tyson hook. Rosemonde's reaction foreshadowed what was to come for Donna and me. (We did indeed marry two months later on a cold, rainy December morning in Crawfordsville, Indiana.) If a black friend could have such a visceral reaction, then you know strangers could be far worse. And they have been.

Responses to our being together depend on the level of agitation and gall people have. Most often, we get the

Why is he with her?

stare, the rolled eyes, the sucked teeth. Every once in a while, a brave soul gets cocky, like the sister in the parking lot one day who muttered, "Jungle fever," as we passed by. We paid her no mind.

I know exactly what the stares are all about. Back in my days at Florida A&M University, a crucible of black activism and black power in Tallahassee, I used to be part of that crowd doing the gaping, perplexed and angered by the sight of a black-and-white couple. I took them as an affront to my race. That they happened to have fallen in love was the furthest thing from my mind. Then I fell in love myself, and my old foolishness became what Donna and I have had to learn to deal with. It doesn't faze us now; we've grown immune. But there was a time when we were on constant alert; ignorance is more often subtle—it tends not to shout. Imagine spending every day, walking into every gathering or restaurant, prepared for the slightest insult. It could wear you down if you let it.

Black women and white men seem to be the most offended by the sight of a black man and a white woman. Some black women even seem to feel that my marrying a white woman is downright pathological. I must hate my mother or maybe myself, right? Wrong. I'm not ashamed or sorry or the least bit uncomfortable with my mother, myself, or my marriage. I do, however, get pissed off when my wife is slighted or intimidated, or when she has to contend with ignorant people. When we lived in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, some years ago, a white mechanic helping Donna with a flat tire became furious at the sight of a black-and-white couple driving into the station. "Look at that," he growled as Donna watched him in disbelief. "You would never do that, would you?" Donna opened her locket and showed him a picture. His face flushed red; he blurted out, "But he's educated, right?"

We've come a long way since the days when a black man was lynched simply for making eye contact with a white woman. In fact there are more than three hundred thousand black-white married couples in the United States today, a number that has risen steadily since the 1970s. But still,

this

black man marrying a white woman was a big deal. I was one of those people who once led the arguments against intermarriage. Because racism remains a source of pain for so many of us in this country, many blacks and whites still view interracial couples as unnatural as horses mating with cows. We're treated as if we're traitors in somebody's grand scheme of things. I'm nobody's traitor; I simply followed my heart.

Donna and I met in Togo, West Africa, brought to that obscure place by our mutual idealistic pursuit of trying to make a difference in the world. I was drawn to her midwestern naivete and easy smile, and she to my northeastern edge and tempo. The attraction—physical and intellectual—was immediate. Even with our differences, we were so much alike. We were both considered radicals in Ronald Reagan's America, where

liberalism

was a dirty word: We had volunteered for the Peace Corps to work in remote rural villages at a time when most of our contemporaries were starting the management training program on the fast track to the Big Time, dreaming of becoming vice president of something. We wanted to teach a trade, share a skill, save a life.

I was born in Haiti and grew up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, a smokestack-filled industrial city about sixteen miles southwest of Manhattan. In the spring of 1987, after graduating from college, I went to Africa to complete the last leg of my own reverse triangular trade. Blacks had left Africa, were taken to South and Central America and the Caribbean, then to the colonies, to keep afloat the peculiar institution that was slavery. I was seeking to connect all the intellectual and spiritual dots. I left FAMU a disciple of Malcolm X (long before X T-shirts were fashionable), and though I never believed in the innate superiority of any race, I was still known to take issue with interracial couples.

So Africa was the last place I expected to be seeing a white woman—the first one I'd ever dated—let alone one I would marry. One of my closest friends, once asked me jokingly, "Garry, did you have to go to Africa to find a white woman? There were plenty in Tallahassee!" I laughed at the irony and thought that ours was in the classic tale of boy meets girl, except boy is caramel-colored and girl is lily-white, and they fall in love in Africa.

When we started dating, I would often ride my motorcycle to Donna's village in the central part of Togo, a sliver of a country nestled between Ghana and Benin. Over the course of a year, we became closer. I was moved by Donna's spirit and the care and concern she showed when working and playing with the local children. Some nights we would walk into the center of town with a flashlight and the stars as our guide to a watering hole. Between sips of hot beer and bites of fried yams, we wondered aloud about how our lives together would be once we returned to America. Were we getting into something we couldn't handle? I was unsure if I could return to Tallahassee for FAMU's homecoming. I was anxious about the hostility that might come from the all-black environment I remembered. I didn't want people faking it either. But mostly, I didn't want to have all those stunned black faces staring at us, thinking I had let the race down.

After a year, Donna and I started to consider marriage. The thought frightened me. It wasn't because I didn't love her or because she didn't share my journalist's urge to travel and explore. It was because she was white. Being together in African villages was one thing—to them we were simply foreigners—but I would be with a white woman in America. At one point, I thought about calling it off. But then I tried to put myself in Donna's place and wondered how I would feel if she came and told me that she loves me dearly and I would make her a perfect husband, but here was a small problem: I'm black.

We had to deal with our families: We'd told them of our intention to marry, and they knew of our racial difference. Under our intense scrutiny, their welcome was genuine.

Donna grew up in Crawfordsville, Indiana, a tableau of Norman Rockwell's America. She studied psychology at Denison University and had been drawn to Africa since reading a book called

Cherry

Ames: Jungle Nurse,

of all things, while in elementary school. Donna's father, Donald Wilkinson, is of Anglo-Saxon stock from rural Illinois. Her mother, Clarissa, is half Irish and half German and grew up in Indianapolis. Neither had ever had much contact with blacks. Still, Donna's mother actually took offense when she learned that her daughter, fearing the worst, had sent her brother a letter before announcing the engagement, trying to gauge their parents' response. The Wilkinsons' welcome was in sharp contrast to the way I was once treated by the mother of a woman I dated in college. Her mother saw me as a cat-eating,

Vodou

-worshipping Haitian American, although I've never tasted the feline and I know as much about

Vodou

as I know about Buddhism. She went so far as to take her daughter, an only child, out of her will in case she lost her mind and married me.

My mother, Yvette, never had any time to harbor ill will toward white people; she was too busy trying to make ends meet and raise me. She, too, embraced the newest member of my family. Getting our parents' blessing turned out to be the easy part.

Some of my friends, like Rosemonde, tried to discourage me from marrying Donna, asking the old question "What about the children?" The race dilemma our kids would face was the least of my concerns: Our world is growing more multicultural by the day, and biracial children are often identified as black. Besides, being Haitian, I've never subscribed to the tragic-mulatto theory. What made the American mulatto's life sad, if it ever was, was not racial identity but rejection by a part of the family. Other relations embraced us as if our union were the most natural thing in the world—as if we were a perfect fit. Donna and I began to see who our friends really were.

As we settled back in the States and headed toward marriage, we confronted more serious problems than racial difference. Several months before our wedding, doctors found a blood clot the size of a golf ball in Donna's head. She underwent surgery to remove it, unsure whether she would ever again be able to speak, walk, or lead a normal life. Then began her recovery: Donna would spend five years on a daily medication and a year in physical therapy, struggling with the simplest sentences. (Today she is healthy but still working to gain full control of her fine motor skills.) Later, as we tried to start a family, she had two miscarriages, one almost took her life.

Other couples may have far less to overcome than we did, but if they're like us, once they decide they're serious, they quickly close ranks against those who would rather see them keep with "their own kind." Nobody's discomfort or anger or annoyance matters more to a couple in love than their being together. We determined that we wouldn't be worn down. Donna and I did this instinctively, without having ever had a conversation about it.

In fact, the first time we talked about how much racism has affected us as a couple was when I started to write this piece. Donna shared her sense of intimidation around some black women, the subtle messages she gets that she's not dressed right or not up to par. "You know when a woman is looking and not approving," she said to me recently, adding that it's something I wouldn't pick up on. "You don't have to have a word said." It angers me that anyone would dare to judge her; she doesn't need to conform to some standard of what a black man's wife ought to be. We also laughed at how some white women take my being with Donna as license to come on to me. A good sense of humor has always kept the ignorant at bay.

It has been more than twelve years since I first met Donna, and after ten years of marriage and two children, we don't have time to worry about what others think of us. With six-year-old Cameron, and two-year-old Mina filling our lives, the stares and whispers of strangers don't matter at all. We have learned to stay away from places where either one of us would be uncomfortable, to choose our friends carefully (we have more black friends than white) and to live in places where we feel safe and secure. That's what any man, of any color, wants for his family.

Since Cameron was born, I've made a herculean effort to make sure that my children are keenly aware of their African heritage. Our walls are festooned with African and Haitian paintings. My music library includes an eclectic collection of jazz, blues, and Haitian and African CDs. This doesn't necessarily mean that my kids won't confront that age-old existential question: Who am I? It is a question that bedevils all of us, regardless of race, religion, culture. I simply want Cameron and Mina to be surrounded by tokens of their African heritage while living in predominantly white America. And we have not shied away from discussing race with Cameron. To him, Daddy is black, Mom is pink, and he is brown. At a recent gathering, when someone pretended not to know this Garry person that Cameron kept talking about, my son simply sighed and answered:

"You know,

black

Garry, my dad."

Everyone laughed.

So if the sight of a black-and-white couple strolling down the street still offends you, it's your problem. We're busy leading our lives and rearing our children and keeping our love alive.

Martine Bury

I am sitting in the home of a gorgeous, famous black actor. A hottie. His skin is ebony and his muscles are toned. There are empty beer bottles everywhere, sultry British music playing. And we're at the point in the interview when we get too much like old friends who used to kiss. We reminisce about Brooklyn and the Haitians we knew growing up. He flirts a little. We spill beans about sex and dating. Then he says something and my knees go weak—for I am self-conscious. He says, "You're the kind of sister that would probably turn her nose up at a brother and not give him the time of day." I don't know how he got my number. But I have a story I wish I'd told him in my defense.

I used to be a strong woman. I even considered myself a modern black woman. But six years ago I had to get stronger over eggplant parmesan. I was sitting at a dinner table with the then love of my life and his Texan parents. We were dining at Santerello on the Upper West Side ogling antipasto and getting drunk on red wine. It was a genteel scene. My mother and father were conspicuously absent— visiting with friends somewhere in Queens, where I should have been. My man and I had just announced that we wanted to move to Texas together. I don't know what I was thinking. It was my Normandy Beach approach to love in full-blown play. So far from East Flatbush where I was born and South Miami where I grew up. Haiti I had buried somewhere just beneath the surface for the night.

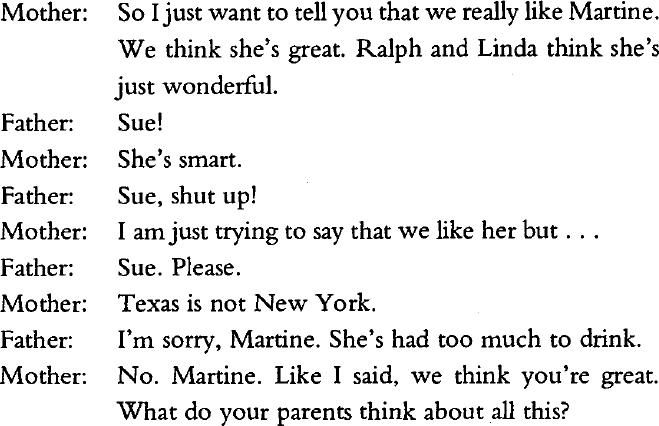

These were really reserved Texans, which made the air thick with unanswered questions. We were all laughing in a guarded way. The dining room was claustrophobic in thick red velvets and heavy woods. Still, as I said, I was in love and these were the colors of earth, familiar skin, tall tree trunks, and a dozen red roses. I was wearing a yellow dress to counteract the stress in my face and bring out those undertones people say I glow with. I wanted to be their friendly yellow rose rather than their black rose, in Texan parlance. There's an offensive Waylon Jennings song that goes "The devil made me do it the first time/The second time I done it on my own/ Better leave that black rose alone." Waylon understated, but my boyfriend's mother, under the influence of too much Chianti, would not be stopped. She and her husband began a conversation that went like this. As if I wasn't there:

I ran to the bathroom to cry. Ralph and Linda were their next-door neighbors of Mexican descent who comprised the majority of their ethnic friends. Texas was not New York. Maybe their son and I could live together in New York, or the Bay Area, but not in Texas.

At the time I was not sure just what my parents thought. I never asked because it would have been like talking about sex. In fact, it

would

have been talking about sex. I presumed that in the Caribbean there was unspoken encouragement of interracial dating. Half Indian, part French, two-thirds Arab . . . you know the drill. My father stayed silent on the issue. My mother was agreeable. It was generally the same response they'd had to every decision I ever made. Summer college. Columbia. Brazil. Freelance writing.

I was a student at Columbia University, and I loved the anonymity of New York at nineteen. With a lover you could blend into the throngs, virtually unnoticed. Part of the landscape of the city are the lovers that fit like the fixtures of dilapidated city apartments: original moldings, faucets, and such. Lovers fit in so well against buildings and urban decay because they are so oblivious to the sweat, crowds, and screechy-bumpy arrested traffic. In a Woody Allen movie, you fall in love with falling in love in the city at the Museum of Modern Art or in Central Park. You always notice the lovers, often mismatched, happy to sit too close on packed subways. There is certain freedom in the back of a yellow taxi to stare into goo-goo eyes, touch and kiss, not mindful of the meter, drunk drivers, or a cabby rolling his eyes at the window display of complete lack of self-control. I would sometimes look at the Haitian name on the I.D. card and think, This man could be my uncle or my father.

Before I messed with Texas I'd had my first significant romance with a graduate student in Russian studies. I noticed then the ostracism that would come to define my lovelife. I would hold hands with my boyfriend and members of the Black Students Association would trip on me as I tripped over campus cobblestone and he would stop me from falling. It's hard to say that their stares were hateful or judgmental. Maybe it was just me projecting my guilt for not being the black girl every one wanted me to be. I was, for the moment, maybe the one that the boyfriend wanted. Trying to belong to him, to me, to my family as well as the Black Students Association, the Haitian Students Association, and the Caribbean Students Association (only a few of the groups of which I never officially became a member). It was like Woody Allen quoting Groucho Marx in

Annie

Hall

about not joining any club that would have him as a member.

Bedrooms are such sacred spaces because they allow you the freedom to explore the things that are truest about you in dreams and with another body. I couldn't say I saw my reflection in my lover's eyes. But I wondered about his fascination with me. Our skin contrasted as much as our styles did. I had extensions in my hair that he loved to look at—but not to touch. It was hard explaining the hair thing to him when he'd secretly looked as if he wanted to touch something about me that was real. As with my Senegalese twists, the line between real and fantasy somehow was blurred. If I stared at my hand on his stomach long enough it would look like a little brown island on a pale pink sea. I wondered if we could ever disappear into each other. I still think of this rather neutrally. As we do with all private thoughts when we're naked. But outside—if we went too far up the Upper West Side, I would be castigated in a glance or by a declaration. "I can't believe she brought a white boy up in Harlem." As if I wasn't there.

From the time we were eight years old, my best friend from childhood and I would sit around spinning tales and telling each other our dreams. I hate to confess it, but we were expert liars. Still, each day after school we'd report to each other elaborate tales of how we'd look, what we'd wear when we were twenty and courting or married to various rock stars and actors. Barring Prince and Michael Jackson, the list was pretty conventional: Leif Garrett, Andy Gibb, Sting, Rick Springfield, Carey Elwes, and Christopher Atkins. George Michael and Andrew Ridgely from Wham! took entirely too big a chunk of our time and creativity. But it went on for years. Shining white knights who would take us away from our little Caribbean community in Miami. My friend's Jamaican parents and my Haitian parents were always conspicuously absent from our ritual imaginings as were families and neighborhoods, patois,

Kreyol, griyo,

and jerk meats.

By high school we'd grown apart, but we still got together to talk about relationships—mostly hers. She had a series of sports-playing significant others. And I'll make it plain: Black boys were not into me. I tried to be down and alluring. I sometimes even let the basketball and football heroes copy my homework. Romantically, however, it was no go. I read Jamaica Kincaid's

Lucy

my first year in college. The main character lives in New York and works as an au pair who sexually crosses racial lines. I got it. It was going to be hard to be any kind of black intellectual as long as you were sleeping with the enemy. James Baldwin wrote about this all the time, making the boudoir the battleground of race war, too.

My grandmother had always shown me photos of my great grandfather who was practically white. She told me while combing my hair that she had a near ancestor who'd fought in Napoleon's army. My aunts and uncles and I have always had white friends. Some have intermarried. I look at my folks' meticulous photo-documentaries of my birthday parties, which were always exceptionally multicultural. I know that they didn't orchestrate this universe for me. It's hard figuring out what my people think of the Man because no one ever said a word to me until recently.

My hippest aunt and I were munching on sushi once. She reported that there were pretty harsh rumors circulating in the family about the fact that I only date white men.

Only?

was my response. It was the same tone I'd used toward my grandmother when I had my hair braided (and when I went natural). She'd asked me on both occasions: "Do you think you are an African?"

"I am just me," I said, sensing that I was never going to make her happy.

I have to say there is something so surreal about having your lover reach over to you in fascination and ask can he touch your kinky hair or tell you that he has never dated a black woman before. There is something cruel and unforgiving when your lover leaves you because he secretly doesn't know how to take love to the marriage point because of the possibility of beige babies. Or because his family is truly irked by you. And there are a lot of utterly disturbing things men have told me like, "There's nothing hotter than a bald black woman giving me head." (I was not bald!) Or, "I find how dark you are really sexy."

Still, I have trodden very foreign territories. I have had blue lights dimmed and Donna Summer played by boys who listened to Rundgren when disco was the shit because they thought it was appropriate. I was told in bed by a French man that I called to his mind Lauryn Hill—but more

sauvage.

But I have also known sweetness. You know, when it all comes down to warmth and eyes staring into each other. So for all these convoluted reasons, I apologize to the tall lanky writer who loved me so very hard he broke both our hearts. He was so country club that I could not hold his hand on 14th Street because I was freaked out by our juxtaposition. Like many black women with their white boyfriends—I didn't want to draw attention. I averted my glance, especially in Brooklyn.

A couple of years ago my therapist, who happened to be white, asked me why I didn't choose someone else to spill my guts to. Presumptuously, I believed at the time that she was titillated by my dating practices. I probably gave her some song and dance then. It hardly seemed an issue to be tortured by. A boyfriend I accused of fetishizing black women told me point blank: "Some men like blondes!" But there were so many whom I wouldn't really touch or kiss in public because I found it exhausting. I felt similarly about seeing a therapist who looked like me. That I would be outed before one of my own seemed like something terrible. It is hard to understand why I lived in so much conflict. I guess I looked back with my psychologist at a stereotypical history of strong Haitian women who emasculated their men and what-not. But I think it's all bullshit now. I open my bedroom door just a crack to the public. Let the people stare because the people have to see me for who I am. Used to feel like a crumbling fortress with Haitian-Black-American rubble falling fast and fragmenting into a billion little pieces. But no more.

One of the great men of my heart was an entertainment industry bigwig. And I loved his world because I felt free and safe in it. It was my girl-child fantasy. In a larger-than-life kind of life, you can swing whatever way you want because people are gonna give you respect no matter what. Illusory? Yes. But this idea made me stronger.

I used to hate that black male celebs could flaunt their white girlfriends and wives, while you rarely even heard about a black actress's love life. I do thank this man for our romantic dalliance. When he broke my heart, I didn't suddenly become paranoid about the great divide. He had been my closest intellectual and emotional mate. When he left my life, I noticed, like a fool, finally, that pain is just pain. He had once made the most tender observation: He was standing somewhere watching an attractive white man with dreadlocks play with his two

cafe au hit

babies. He was so enamored with this vision of what he saw as a real option for himself. When we were together, it didn't occur to me that I was an object of conquest or desire. I now open myself to the universe for a true soul companion.

Sure I want a lover who can dance

konpa,

who's read Baldwin and Achebe and Toni Morrison. I want to say something scandalous about what sends my pulse racing, like tan lines and good diction. I cannot say who fits this bill or what he will look like. But at my shrink's suggestion and for my own peace of mind—here is a note to the man I will always love most.

THE WHITE WIFE

THE WHITE WIFE