Campari for Breakfast (25 page)

‘This one will need pollarding before Spring,’ said Badger as he joined us, referring to the very tree I had been up against.

‘I’ll say,’ I thought quietly to myself. I almost got a kiss.

We all walked back to the house together to find romance flooding the place at every single corner. Nigel was running around the garden, pretending to be Victorian; Derek and Pigpen were in the conservatory writing poetry to their wives; Admiral Ted was in the kitchen attending to Mrs Bunion; and Delia and Admiral Gordon were upstairs talking Italian. The sun teased the dust into kaleidoscope tendrils of love.

Aunt Coral was busy fiddling with her bonnet, temptingly near to the Ad. He was as amorous as he was able to be whilst filling out forms he’d requested for loans on listed buildings.

‘We might just qualify,’ he said.

‘We might,’ said Aunt C throatily, incorrigibly playing with her bonnet.

It hardly mattered when, as expected, Loudolle retaliated over the earlier slights with another ransom demand. I found that the prospect of giving her money didn’t bother me as much as before. Maybe because I felt rich, not in money but in moments, and my moment amongst the apples was mine for ever; it could never be stolen away.

Of course Tornegus is no match for Icarus but he has given me a new perspective, which is a blessed relief. And he took my hands in the orchard, in a flash of rare sunshine and apples; it was not the hand of the man I love, but that of a traveller along the way.

Later

Very late this evening, when everyone was in bed, Aunt Coral came up to the attic.

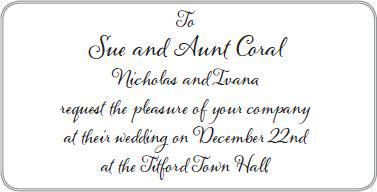

‘I didn’t want to spoil your day,’ she said. ‘But is it what I think it is?’ And she handed me a card addressed to me in my father’s writing and bearing the Titford postmark. I didn’t need to open it. The bad news inside burned through.

If only life could be like the films, where painful nights just melt away into rapid changes of season, to ‘two years later’ or ‘in the end’. If only the pages of the calendar

could

be blown away by the wind and jump-cut to the happy ending. But not so life. You have to live through every heartbeat; there’s no escaping the bad bits.

‘I thought it might be, so I went to fetch this,’ said Aunt Coral, settling on my bed in her cosy. She was holding the bottle of wine from the cellar that she had laid down for my 18

th

.

‘But I’m not eighteen till January,’ I said.

‘I know, but I think it will help.’

She pulled a corkscrew out of her pocket like an alcoholic.

‘It’s a Bordeaux, so we need to let it breathe,’ she said, studying the seventeen-year-old bottle. Although a great connoisseur, she is not above buying a wine because she likes the picture on the label. She gently blew off the dust.

‘I had the telegram about your birth and the next day I chose this. It’s a Château Lafite. The finest. For good luck, long life, and bless—’

She stopped to examine the vineyard closer, and something came off in her hand. It was a damp clump of paper, on top of which you could still see the handwritten letters ‘S’ and ‘U’.

I recognised mum’s writing immediately. I’m not certain if Aunt Coral did too, but I think she took her cue from my face. I remember so clearly the way the ‘E’ would have been had it not been washed away. It would have been up very close to the ‘U’, as if it did not want to be parted from it; it was mum’s trademark way of writing my name.

There was no more script to follow, no point of familiar reference. My teeth chattered, though it wasn’t cold, and Aunt Coral was white as snow. I hadn’t looked in the cellar because Mum was afraid of spiders. She must have really wanted to be certain to hide it away from my Dad.

‘I thought we’d never find it. I stopped believing,’ I said.

‘I don’t feel ready,’ she said. Her voice was fragile but it was as if her hands belonged to a strongman. She opened out the note steadily in preparation for reading. But how could anyone ever be ready for such a thing as this? If we’d been in a film, we would have had special clothes on; we would have been in a solicitor’s, with professionals on hand in case one of us couldn’t cope. But instead we were in an attic, in ordinary lamplight and dust, with no one but each other. It wasn’t enough. We couldn’t have been any closer, yet Aunt C was far away, and at the end of the awful hunt, we were each on our own.

The sound of footsteps down the passage released us into action.

‘OK,’ I said. It was as good a word as any.

My darling Sue,

There is not a word or a number that can ever express how much I love you. I’m so sorry for what I have done. And I hope that if you are reading this on your birthday it means that you are with Aunt Coral. She is the best of aunts and sisters, and I know she will take care of you.

I was so lucky to have had you, had the joy of you all your years. The fact that I can’t bear my sadness is my weakness, not yours.

I’ve left you a bundle of things in a locker at Titford Station. The key is under the floorboard in my bedroom, and the locker is 402. This is just between you and me, please keep it private. I am sorry to be so secretive, but I do think it’s for the best.

I wonder if you’d ask Coral to put a little plaque up for me in the garden? Maybe out next to my mother’s? It’s somewhere I always liked to be.

I’m so sorry I left without saying goodbye, but you know I couldn’t have managed it.

Forgive me my darling, please forgive me.

I love you so very much,

Mum XXXXXX

Sometimes it feels as though every silver lining has a cloud. The answer I’ve been searching for ever since Mum died is finally there on paper, dotted with Aunt C’s tears and made a mash of by the drips in the cellar, but it isn’t the answer I want. It is the dawn of many more questions.

There are some things she said I feel I understand, and some that I really don’t. I understand what she means by not being able to bear her own sadness, that must be about Dad and Ivana I’m sure. But why would she go to all the trouble of hiding things in a locker? And why did she feel the need to be secretive, and why did she think it was for the best? She didn’t have anything to hide, or anything to be ashamed of that I know of. Perhaps feeling that Dad didn’t care about her drove her to hide her precious things.

Although in a way it is a grisly relief, to be sure that she really

meant

to do this. That it wasn’t an accidental cry for help, and there was nothing I could have done to prevent it. And maybe Aunt Coral is right. Maybe finding out she wasn’t who she thought she was did hurt her. She was such a sensitive person, it must have been such a shock. And she didn’t even have Dad’s companionable shoulder to cry on when she found out, because of Ivana. These thoughts are unbearable and to survive I must stop.

Aunt C checked on me about ten times before I persuaded her to go to bed. She knows that sometimes all one can do is stand by on the same roadside. I know how she’ll get through it; she’s pretty classy at comforting herself. She’ll go down and rummage in her papers, keep her radio on and get an extra quilt.

But I just want to be alone, I feel hollow, as though I have no blood, bones or veins inside me. I can only tell you that finding that note actually physically hurts.

I have put it in my sock drawer, where I can catch a glimpse of her lovely writing. To have put it in my treasure box would have felt like excluding her, shutting her away from the light, and under my pillow was too painful, and under my bed too dark. But the sock drawer is sometimes open, sometimes closed. It is very much part of my actions, and my actions are still alive. I cling to these little things like odd bits of ship wreck drifting about in an open sea.

We must carry on, we mustn’t collapse; I’ve learnt this very strongly. And if we do stop carrying on for a while, life carries on without us. And so when the sun rises, if it does, I will face the second day of the Chivalry workshop, with the best courage I can.

Even at such grave moments as this, my mind tries to balance itself with the practical. How am I going to get the key from under the floorboard in Dad’s room? He barely leaves the house when they’re there; they prefer to stay home, loving. And what could there be in the locker that is so dire and dreadful? I think there will be little sleep for me tonight.

Sunday

At about 9am, the tired sky let through a single shaft of light, which looked briefly like a followspot falling through my skylight. It woke me and I went to look out over Egham in the brand new day. But the beam was gone in a nanasecond and the clouds reformed their cover.

Loudolle has such a strong nose for unrest that she sniffed out my upset’s region, like an emotional sommelier who wanted to add some depth to it.

‘Have you got an admirer?’ she asked at breakfast, eyeing my gift of Sunday chocolates. Tornegus had brought them for me, but even they had failed to lift my mood.

‘Nice for you to have someone to take to a party – or a wedding?’

I don’t know how she knew – maybe Aunt Coral had said something – but I am constantly staggered at the extremes of Loudolle’s cruelty. My Mum is dead, it is no joke. I wonder how she would feel if, one night, after sitting up writing letters to herself, Delia committed suicide, and under a year later Ralph and some awful woman got married before Delia’s shoes had gone cold. But, as much as I hate her, I hope that she never has to know that pain, which is something I would not wish even on the devil himself.

‘It’s an admirer more than you’ve got,’ I said in reply. ‘You can’t even pull the Admiral. And it’s downhill from here on as far as your looks go, Loudolle. Then what will you have left?’

‘I think you should show me some more respect or I’m going to tell Icarus about you and his eye.’

I should’ve said ‘Tell him, then, I don’t care’, but the thought of working beside Icarus, with him

knowing I bedded his eye

, was just over-whelming. Though what on earth does it matter in the light of finding Mum’s note? I must have terrible pride for his dumb eye to affect me that much.

By eleven o’clock the gentlemen were forced indoors by the rain. The sky, which had been bulging with hot air, finally burst, and the roof, the gutters and the buddleia did not do well in the deluge. The rain was so heavy it sounded like waves crashing against a piano. I imagined when it finally stopped and the sun came out, it would be accompanied by a Caribbean steel band.

Prior to putting out buckets in which to catch all the water, Aunt Coral had arranged for Loudolle to do our hair in the drawing room before the finale banquet. It wasn’t possible to say no, because Aunt Coral wanted to wave an olive branch at Delia for being rude to her daughter. And once it became a decision, she got carried away and set up the drawing room as a salon, with nail wear and lady materials. She placed the hot seat in front of the window, so that the reluctant customer could view the downpour whilst having their hair done. Before my turn, I tried to ease my countless tensions by replying to my father’s invitation.

Dear Mr Bowl

,

Your affair with Ivana Schwartz was the cause of the turmoil and distress which killed my mother and it will not surprise you to hear that I will not be attending your wedding.

You drove her to despair, you dance on her grave, and you are an offence to her memory.

S.

He no longer deserves anything from me: compassion, empathy, not even the three letters of my name. How can he marry so soon after losing her? Let alone marry the biggest moron in the whole of Scandinavia? It is an abomination. I hope that my absence at the wedding will speak much louder than words.

‘Sue,’ said Aunt Coral, leaving the hot seat. ‘Your turn.’

Aunt Coral and Delia were now both pouffed to the nines, with Aunt Coral’s hair a vengeful purple. I went into Loudolle’s chair like she was my executioner, and she went to work on me in a frenzy, while behind us the ladies applied creams.

‘Mmm, your hair is gorgeous,’ she said, but I could tell what she was thinking.

Mmm, nice hair. Let me glue it and maul it for you and make you look twice your age and five times as depressed

.

And my thoughts replied:

Thank you, whore of deceit, but I’d have been happier without a birds nest

.