Capitol Men (27 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

Pinchback traveled upriver to the scene of the massacre and was overwhelmed by the magnitude of the devastation. In his brief tenure as Louisiana's governor a few months earlier, he had tried unsuccessfully to arrange for either General Longstreet or federal forces to establish control of outlying districts like Grant Parish, and it saddened him to see the terrible consequences of that policy's failure. Back in New Orleans he joined concerned black citizens at an emotional meeting, where resolutions of protest were drafted and comparisons made to the wartime slaughter at Fort Pillow, where Confederates under the command of General Nathan Bedford Forrest notoriously massacred surrendering black troops. Pinchback, upon reaching the podium, recited from Shakespeare ("Give me no help in lamentation. /1 am not barren to bring forth complaints. / All springs reduce their currents to mine eyes, / That I, being governed by the watery moon, / May send forth plenteous tears to drown the world") and urged the gathering to disregard press accounts that had characterized the events at Colfax as a "race war." It was, he insisted, a confrontation between citizens defending a legitimate Republican state government outpost and bitter Southern men determined to carry Louisiana backward into the past. Refuting the notion that the blacks had been the aggressors, Pinchback noted, "My knowledge of their temperament and disposition teaches me that they would not be guilty of the wrong alleged, for the obvious reason that they know too well what would be the inevitable result, owing to the immense disparity between the numbers of white and colored people in this country."

Pinchback condemned the fact that the massacre would surely intimidate blacks and keep them from voting, and he returned to criticisms he had, as governor, leveled at the McEnery factionâabout white Louisianians' unwillingness to accept the changes the war had brought and the weakness of moderate whites who might exercise a controlling influence on the most vicious white element. "A large number of white people feel just as sad as we do," he told his colored listeners, "but unfortunately for them they dare not come out and express their opinion. They are ground down in a slavery worse than ours was. They are slaves to a mistaken public opinion."

Whereas the Memphis and New Orleans riots of 1866 and the Klan violence of 1870â71 had motivated Congress to take action that would safeguard the freedmen, it was the strange fate of the Colfax massacre to spark a federal judicial decision that inhibited that protection. As ever, the Justice Department was faced with the awkward challenge of prosecuting mob violence and murder with statutes designed to protect civil rights. The United States initially indicted ninety-eight whites under the Enforcement Acts, which outlawed conspiracies to deny such rights, but ultimately brought only nine men to trial. Despite graphic testimony from witnesses, one defendant was acquitted; the trials of the remaining eight ended with a hung jury. In a second trial, the defendant William Cruikshank and two others were convicted; these verdicts were appealed to the Supreme Court.

In a landmark decision,

United States v. Cruikshank

(1876), the Supreme Court voted unanimously that the indictments were improper, ruling that the right of citizens to assemble was protected as a federal right only if they did so for the purpose of petitioning Congress or for anything else directly connected with the federal government; any other assembly, such as that of the black defenders at Colfax, was not protected by federal law. Echoing the court's actions three years earlier in the

Slaughterhouse Cases,

the ruling in

Cruikshank

further stipulated that guarantees of due process and equal protection promulgated in the Fourteenth Amendment restricted only the states and offered no protection regarding actions involving individuals. Essentially, this meant that though states could not deprive citizens of life, liberty, property, or equal rights without due process of law, the federal government had no jurisdiction when private citizens, such as a mob or a vigilante army, did so. The part of the indictment that invoked the Enforcement Acts was thrown out on the grounds that there was no allegation that the victims' race had anything to do with the assault on the courthouse.

"This racist and morally opaque decision," argues the historian Ted Tunnell, "reduced the Fourteenth Amendment and the Force Acts to meaningless verbiage as far as the civil rights of Negroes were concerned." After all, notes the scholar Eugene Gressman, "it was private action, not state action, that had caused so much of the postwar bloodshed and atrocities in the South ... It was private action, not state action, that had been the prime motivation for all the toil and debates that produced the Fourteenth Amendment and the surrounding legislation."

When the case against the perpetrators of the Colfax massacre proved unprosecutable, the highest court in the land concluded that the problem lay in the overreaching nature of the statutes violated; it then proceeded to render those laws meaningless. By gutting the Enforcements Acts and placing private actions beyond the reach of the federal judiciary, the decision left Southern blacks in a position of greatly increased vulnerability.

The only silver lining in the aftermath of the crime was the broadly shared sense of shame and violation; the nation, as had Pinchback and others, reacted strongly to the killings in Louisiana. The blaring

New York Times

headline "A Second Fort Pillow: Surrendered Negroes Butchered in Cold Blood" was typical of the outcry. "The war between the races, so constantly carried on in this distracted state," noted the paper's editorial, "has seldom presented such a horrifying instance as this burning of a courthouse filled with human beings ... the terrible scenes enacted at Colfax Courthouse ... appear to be more like the work of fiends than that of civilized men in a Christian country."

America, it seemed, still cared about the inequities Reconstruction aimed to alleviate; the question was how long it would honor that commitment.

CAPSTONE OF THE RECONSTRUCTED REPUBLIC

S

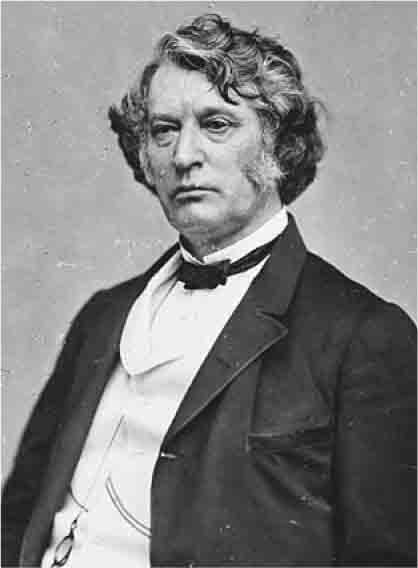

ENATOR CHARLES SUMNER'S BREAK

with President Grant in 1872 was a troubling development in the eyes of most black Americans, and not solely because of its detriment to the electoral fortunes of the Republican Party. Sumner was the primary force behind a controversial piece of legislation then making its way through Congress, a civil rights act (called the Supplementary Civil Rights Act, for it would expand on those rights granted by the Civil Rights Act of 1866) that would for the first time guarantee citizens everywhere equal access to public accommodations. First introduced by Sumner in May 1870, and reintroduced twice in 1871, the bill stipulated that no public inns or places of public amusement for which a license was needed, no railroads or stage lines, charities or cemeteries, no churches or jury boxes, and no schools supported at public expense should make any distinction as to admission on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

This initiative was an effort to finalize the work of Reconstruction by establishing civil rights not simply at the ballot box but in the public sphere where Americans lived their daily lives. As South Carolina congressman Alonzo Ransier said in support of the bill, "We cannot ... educate our children, defend our lives and property in the courts, receive the comforts provided in our common conveyances ... and, in short, engage in 'the pursuit of happiness' as rational beings, when we are circumscribed within the narrowest possible limits on every hand, disowned, spit upon, and outraged in a thousand ways."

Sumner found authority for his civil rights law in some inspired

placesâthe Thirteenth Amendment, of course, which had abolished slavery and, by interpretation, all "badges of slavery" (in Sumner's view, discrimination that publicly set blacks apart as an inferior class was surely a "badge of slavery"), but also the Declaration of Independence and the Sermon on the Mount, sources "earlier in time, loftier, more majestic, more sublime in character and principle" than the Constitution itself. Sumner's conviction that the Declaration of Independence's "pledge of universal human equality was as much a part of the public law of the land as the Constitution" was a faith he had in part adopted from former president John Quincy Adams, who, in old age, received Sumner frequently at his home outside Boston. Since the U.S. Constitution was famously evasive on the subjects of race and slavery, Sumner saw the Declaration as a more valuable and useful instrument in relating America's core principles to the problem of racial equality. He considered the Constitution, drafted in Philadelphia in 1787, to be a pragmatic, "earthly body," while the Declaration, penned by Jefferson at the very moment of America's creation in 1776, was "the soul" of the United States.

The federal government could not watch over each and every interaction between white and black Americans, enforcing equality on an individual basis, but Sumner hoped that by authorizing penalties for those who discriminated and offering legal recourse to their victims, the nation would ultimately choose compliance, and race relations would evolve favorably. This formalizing of equal rights under the law was, for Sumner, "the subject of subjects," a matter that would "not admit of postponement or hesitation"; he saw his bill as "the capstone of the Reconstructed Republic" and a fitting culmination to his life's work.

CHARLES SUMNER

That effort had begun as early as 1849, when he was the attorney in a case seeking change in Boston's segregated schools. Sumner lent his representation pro bono to the plaintiff, a five-year-old child named Sarah Roberts, at the request of her father, Benjamin, who was a local black

leader. The complaint in

Sarah Roberts v. the City of Boston

was that the city's policy of segregating pupils by race defied more general Massachusetts standards of equality. The chief primary school used by black children in the city was in disrepair and far inferior to the schools white children attended, yet spokesmen for the schools insisted that the difference was "one which the Almighty has seen fit to establish, and it is founded deep in the physical, mental, and moral natures of the two races. No legislation, no social customs, can efface [it]." Sumner alleged that the school committee had no right to this position, as the Massachusetts Constitution itself had never made such a distinction. To assert the concept of equality before the law, he alluded to the Declaration of Independence, the writings of the eighteenth-century French

philosophes,

and the Bible. The Boston schools, in defying the most fundamental ideals of equality, he said, were "condemned by Christianity."

In arguing the Roberts case, Sumner described both the inferior physical character of the Negro school Sarah Roberts was made to attend and the destructive psychological and sociological effect of segregation on childrenâboth blacks and whites. "The whites themselves are injured by the separation. Nursed in the sentiment of caste, receiving it with the earliest food of knowledge, they are unable to eradicate it from their natures." Later, Sumner would observe that segregation "cannot fail to have a depressing effect on the mind of colored children, fostering the idea in them and others that they are not as good as other children," anticipating by a century the principal rationale used to defeat legalized segregation in America's public schools in 1954 and, by extension, all Jim Crow restrictions. Sumner's brief, however, was rejected by the Massachusetts Supreme Court, which deemed it extravagant and overly reliant on abstract philosophical arguments.

A generation later, the school clause in Sumner's Supplementary Civil Rights legislation helped spark the first national dialogue on the subject, pitting the ideals of equality in education and the eradication of racial prejudice against concerns over states' rights and forced "social equality." Most people declared the nation unprepared for mixed education and were inclined to treat the question of the clause's legitimacy as not only an abstraction but also possibly dangerous, for the certain result of such a mandate would be that whites would desert public schools. Reports had already emerged from the South that Sumner's planned legislation was inhibiting school construction projects. But such warnings emanated not solely from below the Mason-Dixon Line; the

New York Times

also recommended that the matter be tabled until greater national progress in race relations was achieved. Even many black spokesmen, who agreed with Sumner that separation likely had a hurtful effect on black children, were willing for now to surrender the concept of equality in the interest of keeping education itself available.

Sumner remained steadfast, however, his very public leadership on the issue bringing to his desk each day fresh testimony from black Americans relating their inability to enjoy equal access in public life. "How is it possible for one who has never been denied any of these privileges," Sarah Thompson of Memphis asked Sumner in early 1872, "to express so fully and clearly the profound sense of humiliation which we feel?" Thompson explained that she and her four young children had been barred from a railroad waiting room in Louisville: