Capitol Men (43 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

Representative Joseph Rainey, in urging his congressional colleagues to increase troop levels in the South, could bear personal witness to the soldiers' importance. Traveling by horseback to a Republican rally one day in the town of Bennettsville, South Carolina, he and about sixty fellow Republicans were confronted suddenly by an armed contingent of more than a hundred whites who had gathered from the surrounding counties; a few had crossed the border from North Carolina. They brandished shotguns, ax handles, and other weapons. Not a moment too soon, a company of federal troops rode into view. They had been tipped off about the confrontation and quietly defused what could have been a very bloody scene. "The presence of the troops was most providential," Rainey told the House. "I am confident that members of both parties who are alive at this time, if it had been otherwise, would have been numbered among the dead."

When white congressmen seemed unable to grasp the full import of what had occurred at Hamburg, Rainey used an analogy to issue a powerful demand:

What would be thought if here in Washington City, when a military company was parading on the Fourth of July, two men should come up in a buggy and demand of the officers that the company should get out of the way, and, if they did not, should at once set to work and murder the men of that military company? I ask you, citizens of the United States, would you stand for it? I ask you, proud Southern men who boast of your gallantry and your intelligence and your superiority to my race, would you stand it? I ask you, men of the North, who sacrificed your blood and treasure, who sacrificed the lives of your sons and your relatives, would you stand it?

Do you, then, expect Negroes to stand all this? Do you expect my race to submit meekly to continual persecution and massacre by these people in the South? In the name of my race and my people, in the name of humanity, in the name of God, I ask you whether we are to

be American citizens ... or whether we are to be vassals and slaves again? I ask you to tell us whether these things are to go on, so that we may understand now and henceforth what we are to expect.

Robert Smalls also worked to ensure that Hamburg would not be swept under the carpet, producing in Congress the graphic letter he had received from an eyewitness to the Hamburg affair. When he was pestered by Democratic representatives to name the writer of the letter, he replied, "I will say to the gentleman, if he is desirous that the name shall be given in order to have another negro killed, he will not get it from me," and insisted that he himself could vouch for the letter's authenticity. The Ohio Democrat Samuel Cox, known for his sarcasm, then asked Smalls who would vouch for

him

. "A majority of 13,000," Smalls shot back, referring to his Sea Islands constituents and cutting off the titters Cox's query had prompted. Cox then began reading from

The Prostrate State

by James'S. Pike, but had not gone far when Smalls, unwilling to hear South Carolina demeaned, inquired, "Have you the book there of the city of New York?"

The entire House burst into laughter. A New York Republican then chimed in, reminding Cox that "nothing in South Carolina could match his own state's record of extravagance and dishonesty under the Democrats." Cox, fuming, insisted that "South Carolina is today a Republican state and the worst governed state in the Union; it is bad all around, bad at its borders, bad at its heart; bad on the sea-coast ... everywhere rotten to the core. Give South Carolina a democratic government," Cox vowed, "and you will see that every man, black and white, will be cared for under the law."

Deadpanned Ohio's James Garfield, "As they were at Hamburg?" Smalls managed to tack on an amendment to the troop redeployment bill ensuring that adequate troop levels would be maintained in South Carolina.

In their correspondence, Chamberlain pointed out to President Grant that what had occurred at Hamburg did not auger well for the coming elections, in that it had terrorized the black population and brought "a feeling of triumph and political elation" to "the minds of many of the white people and Democrats. The fears of the one side correspond with the hopes of the other side." Grant responded that he too feared for the upcoming fall election, when the country's greatest civil right, "an untrammeled ballot," might well be put in jeopardy, and agreed that South Carolina was on the brink of the same violence that had so recently restored Mississippi to the hands of the former slave-owning class. "Mississippi is governed today by officials chosen through fraud and violence, such as would scarcely be accredited to savages, much less to a civilized and Christian people," Grant conceded. "How long these things are to continue, or what is to be the final remedy, the Great Ruler of the universe only knows."

When in early September a court convened in Aiken County, South Carolina, to consider charges of murder and conspiracy against Mathew Butler and other whites involved at Hamburg, every lawyer in the county offered to work pro bono to defend the accused. For good measure, a local vigilante leader Benjamin Tillman led a large contingent of men "armed to the teeth," many from his Sweetwater Rifle and Sabre Club, to surround the courthouse and await the court's deliberations. Because in the wake of Hamburg, Republicans like Elliott and Chamberlain had so vehemently "waved the bloody shirt," Tillman had the sympathetic womenfolk of Aiken daub forty shirts with red ink and turpentine, which some of his men wore to mock the traditional Republican complaint, a vivid form of protest that had originated the year before in Mississippi. He also had a huge mask created of a "Negro" with kinky hair, covered it with threatening slogans, and filled it with bullet holes. On one side read the motto

AWAKE, ARISE, OR BE FOREVER FALLEN,

and on the other,

NONE BUT THE GUILTY NEED FEAR.

Dressed in their "bloody" clothes, carrying the grotesque mask, Tillman's mounted men began galloping back and forth through the streets of Aiken, with the horses' hooves raising an immense cloud of dust. It frightened away any would-be black spectators yet won cheers and applause from some of the federal troops on hand. When the judge hearing the cases announced he was considering waiting until the next morning to begin, the sheriff whispered, "You had better let these men get out of town tonight else they may burn it, and hang you before morning." The court wisely wrapped up its proceedings, saying it would bring no indictments, and the "red shirt" that day became the popular uniform of the Edgefield movement in South Carolina. The state, and the nation, would soon hear much more of Captain Tillman and his men.

With no legal action pursued against Butler's men, whatever moderate sympathy that had existed in South Carolina for the Hamburg victims quickly melted away, especially as the hotly contested 1876 elections approached. When, during a campaign appearance in rural Abbeville that fall Governor Chamberlain began to speak of the tragedy that had

befallen Hamburg, he recognized the unmistakable sound of numerous pistols being cockedâa reliable indication in Reconstruction South Carolina that an audience had wearied of a subject.

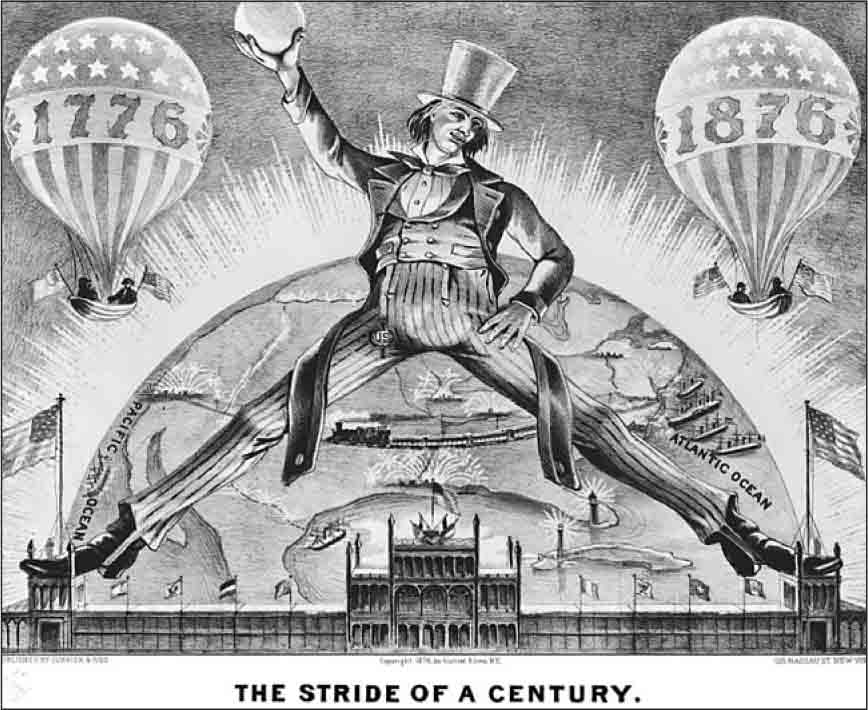

Eighteen seventy-six was a year of well-deserved celebration, as Americans gathered at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia to mark the hundredth birthday of the United States. It was a moment to anticipate the future and to survey with pride the tremendous distance the nation had come from its colonial origins a century before.

PROMOTIONAL ARTWORK FOR THE CENTENNIAL EXPOSITION OF 1876

The country was now several times the size of the original thirteen colonies (that year adding Colorado as the thirty-eighth state), with a population that had grown ten times over and now approached forty million. American industry, no longer located at the village forge or clockmaker's, was to be found in sprawling mills and factories. Manufacturing had been transformed by automated lathes and the sewing machine, agriculture by mechanized plows and threshers. Railroads spanned the country coast to coast, and San Francisco to New York was now a six-day run; harbors and rivers teemed with vessels carrying passengers and freight; and from port cities steamships embarked on transoceanic voyages. Chicago, still rebuilding from the great fire of 1871, had taken over from Cincinnati as the nation's meat-packing center, helping to launch a new system of nationalized food production and distribution. The first professional intercity baseball organization, the National League, was recently formed; Alexander Graham Bell had patented a newfangled device he called "the telephone"; and Mark Twain, one of America's leading humorists, had just published a semi-autobiographical novel of simpler times titled

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

The reach of the nation's press had expanded. News of catastrophes such as train wrecks and the massacre of Custer and his troops were sped to readers, and the first sensational kidnapping for ransom riveted the public when four-year-old Charley Ross was abducted from the front yard of his family's home in Germantown, Pennsylvania, held for $20,000, and never seen again. The press coverage of "Little Charley's" vanishing was obsessive enough to compete with that surrounding the Beecher-Tilton scandal, which involved a sexual dalliance between the sanctimonious Henry Ward Beecher and Elizabeth "Lib" Tilton, wife of the New York editor Theodore Tilton. The Beecher-Tilton saga, the decade's longest-running newspaper soap opera, featured free-love advocates, spiritualists, and eastern intellectuals, and it made for irresistible copy while offering proof of the moral turpitude of even America's "best people." Less salacious but equally steadfast were the reports of official wrongdoing, thievery, and crooked financial dealings emanating from Washington and Wall Street, as well as accounts of abusive labor practices in the steel mills and on the railroads. "There has been so much corruption," one observer could only conclude, "the man in the moon has to hold his nose as he passes over the earth."

Also darkening the centennial mood were lingering economic woes from the Panic of 1873, which had begun in September of that year, with the failure of Jay Cooke and Company, America's leading investment house. Depositors rushed their banks and investors besieged brokerage houses, and for ten days the New York Stock Exchange remained shuttered. Ripples from the collapse in the East coursed across America to the plains and to the cotton plantations of the Mississippi Delta. Falling agricultural prices exacerbated tensions related to land and labor in the South; farmers cried out against railroads' price gouging; in Northern cities, hard-pressed workers and the unemployed marched for relief.

The widely shared anguish caused by the downturn served as another

breaking point in the North's interest in the freedmen.

CIVIL RIGHTS HAVE PASSED, NOW FOR THE RIGHTS OF WORK,

a banner read at a rally in New York's Cooper Union, a blunt expression of a shift in mood as the dilemma of black field hands in the plantation South gave way to the growing concern for industrial labor relations and the plight of the immigrant working classes. The ex-slaves, many Americans felt, had already enjoyed a very long day as the nation's darlings.

Moreover, public faith in the president had fallen off even more precipitously. By now, the country was nearly a full decade removed from the days of Andrew Johnson's "Swing Around the Circle," when audiences stood in the rain and begged for a glimpse of Grant, the Union's military savior. To the glory of his battlefield successes, unfortunately, were now added years of bruising politics and widespread concern about his probity and competence. In the Whiskey Ring affair that came to public attention in 1875, it was revealed that midwestern businessmen had bribed members of Grant's inner circle to issue an illegal tax abatement on whiskey, causing the United States to forfeit almost $3 million in tax revenues. Later it was discovered that some of the money wound up funding Grant's reelection campaign of 1872 and paying for gifts for him and some of his associates; these included a team of horses given to the president and a $2,400 diamond shirt stud presented to Orville E. Babcock, the president's secretary.

A more embarrassing scandal involved Secretary of War William Worth Belknap, who was found to have engaged in a number of profitable schemes, including the "sale" of a U.S. military trading post in the West. Belknap was married to one of Washington's most fashionable society women, Amanda "Puss" Tomlinson, the sister of his late wife, Carrie. Before her death from consumption in 1870, Carrie Belknap had made arrangements so that a friend, Caleb P. Marsh, would receive the post tradership at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. The sale of these lucrative positions was common, but Marsh's case was complicated in that the present owner of the Fort Sill tradership, John Evans, did not wish to relinquish it. Marsh arranged for Evans to keep the post but pay him $15,000 annually (later reduced to $12,000), half of whichâMarsh agreed with Carrie Belknapâwould go to maintain a trust for her infant son. When Amanda Tomlinson assumed her deceased sister's place as the new Mrs. Belknap in 1873, she continued with the scheme, even though the child had died in 1871. Puss apparently used money from the "trust" to enhance her wardrobe and to fund her and her husband's active social life. That the secretary of war himself knew of the arrangement was made

evident by Marsh's testimony that he had on occasion paid the money to Belknap directly.