Cat O'Nine Tales: And Other Stories (16 page)

Read Cat O'Nine Tales: And Other Stories Online

Authors: Jeffrey Archer

This left only

the red king to be unearthed.

The family had

for some time been paying well over the odds for any missing pieces, since

every dealer across the globe was well aware that if Lady

Kennington

was able to complete the set it would be worth a fortune.

When Elsie

entered her ninth decade, she informed her sons that on her demise she planned

to divide the estate equally between the two of them, with one proviso. She

intended to bequeath the chess set to whichever one of them found the missing

red king.

Elsie died at

the age of eighty-three, without her king.

Edward had

already acquired the title–something you can’t dispose of in a will–and now,

after death duties, also inherited the Hall and a further £857,000.

James moved

into the

Cadogan

Square apartment, and also received

the sum of £857,000. The

Kennington

Set remained in

its display case for all to admire, one square still unoccupied, ownership

unresolved. Enter Max Glover.

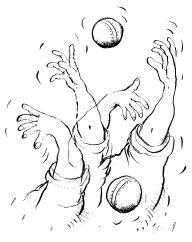

Max had one

undisputed gift, his ability to wield a willow. Educated at one of England’s

minor public schools, his talent as a stylish left-handed batsman allowed him

to mix with the very people that he would later rob. After all, a chap who can

score an effortless half century is obviously somebody one can trust.

Away fixtures

suited Max best, as they allowed him the opportunity to meet eleven potential

new victims.

Kennington

Village XI was no exception.

By the time his lordship had joined the two teams for tea in the pavilion, Max

had wormed out of the local umpire the history of the

Kennington

Set, including the provision in the will that whichever son came up with the

missing red king would automatically inherit the complete set.

Max boldly

asked his lordship, while devouring a portion of Victoria sponge, if he might

be allowed to view the

Kennington

Set, as he was

fascinated by the game of chess. Lord

Kennington

was

only too happy to invite a man with such an effortless cover drive into his

drawing room. The moment Max spotted the empty

square,

a plan began to form in his mind. A few well-planted questions were

indiscreetly answered by his host. Max avoided making any reference to his

lordship’s brother, or the clause in the will. He then spent the rest of the

afternoon at square leg, refining his plan. He dropped two catches.

When the match

was over, Max declined an invitation to join the rest of the team at the

village pub, explaining that he had urgent business in London.

Moments after

arriving back at his flat in Hammersmith, Max phoned an old lag he’d shared a

pad with when he’d been locked up in a previous establishment. The former

inmate assured Max that he could deliver, but it would take him about a month

and “would cost ‘

im

.”

Max chose a

Sunday afternoon to return to

Kennington

Hall and

continue his research. He left his ancient MG–soon to become a

collectors

item, he tried to

convince himself–in the visitors’

carpark

.

He followed

signs to the front door, where he handed over five pounds in exchange for an

entrance ticket. Maintenance and running costs had once again made it necessary

for the Hall to be opened to the public at weekends.

Max walked

purposefully down a long corridor adorned with ancestral portraits painted by

such luminaries as Romney, Gainsborough, Lely and Stubbs. Each would have

fetched a fortune on the open market, but Max’s eyes were set on a far smaller

object, currently residing in the Long Gallery.

When Max

entered the room that displayed the

Kennington

Set,

he found the masterpiece surrounded by an attentive group of visitors who were

being addressed by a tour guide. Max stood at the back of the crowd and

listened to a tale he knew only too well. He waited patiently for the group to

move on to the dining room and admire the family silver.

“Several pieces

were captured at the time of the Armada,” the tour guide intoned as the group

followed him into an adjoining room.

Max looked back

down the corridor to check that the next group was not about to descend upon

him. He placed a hand in his pocket and withdrew the red king. Other than the

color, the intricately carved piece was identical in every detail to the white

king standing on the opposite side of the board. Max knew the counterfeit would

not pass a carbon-dating test, but he was satisfied that he was in possession

of a perfect copy. He left

Kennington

Hall a few

minutes later, and drove back to London.

Max’s next

problem was to decide which city would have the most relaxed security to carry

out his coup: London, Washington or Peking.

The People’s

Palace in Peking won by a short head.

However, when

it came to considering the cost of the whole exercise, the British Museum was

the only horse left in the race. But what finally tipped the balance for Max

was the thought of spending the next five years locked up in a Chinese jail, an

American penitentiary, or residing at an open prison in the east of England.

England won in a canter.

The following

morning Max visited the British Museum for the first time in his life. The lady

seated behind the information desk directed him to the back of the ground

floor, where the Chinese collection is housed.

Max discovered

that hundreds of Chinese artifacts occupied the fifteen rooms, and it took him

the best part of an hour to locate the chess set. He had considered seeking

guidance from one of the uniformed guards, but as he had no desire to draw

attention to himself, and also doubted that they would be able to answer his

question, he thought better of it.

Max had to hang

around for some time before he was left alone in the room.

He could not

afford a member of the public or, worse, a guard, to witness his little

subterfuge. Max noted that the security guard covered four rooms every thirty

minutes. He would therefore have to wait until the guard had departed for the

Islam room, while at the same time being sure that no other visitors were in

sight, before he could make his move.

It was another

hour before Max felt confident enough to take the bastard out of his pocket and

compare the piece with the legitimate king, standing proudly on its red square

in the display cabinet. The two kings stared at each other, identical twins,

except that one was an impostor.

Max glanced

around–the room was still empty. After all, it was eleven o’clock on a Tuesday

morning, half term, and the sun was shining.

Max waited

until the guard had moved on to Islamic artifacts before he carried out his

well-rehearsed move.

With the help

of a Swiss Army knife, he carefully

prised

open the

lid of the display cabinet that covered the Chinese masterpiece. A raucous

alarm immediately sounded, but long before the first guard appeared, Max had

switched the two kings, replaced the cover of the case, opened a window and

strolled casually into the next room. He was studying the costume of a samurai

when two guards rushed into the adjoining room. One cursed when he spotted the

open window, while the other checked to see if anything was missing.

“Now, you’ll

want to know,” suggested Max, clearly enjoying

himself

,

“how I trapped both brothers into a fool’s mate.”

I nodded, but

he didn’t speak again until he’d rolled another cigarette. “To start with,”

continued Max, “never rush a transaction when you’re in possession of something

two

buyers want, and in this case,

desperately

want. My next visit...” he

paused to light his cigarette...”was to a shop in the

Charing

Cross Road. This had not required a great deal of research, because they

advertised themselves in the

Yellow Pages

under Chess, as Mar-

lowe’s

,

the people who serve the masters

and advise the beginners.”

Max stepped

into the musty old shop, to be greeted by an elderly gentleman who resembled

one of life’s pawns: someone who took the occasional move forward, but still

looked as if he must eventually be taken–certainly not the type who reached the

other side of the board to become a king. Max asked the old man about a chess

set that he had spotted in the window. There then followed a series of

well-rehearsed questions, which casually led to the value of a red king in the

Kennington

Set.

“Were such a

piece ever to come onto the market,” the elderly assistant mused, “the price

could be in excess of fifty thousand

pounds,

as

everyone knows there are two certain bidders.”

It was this

piece of information that caused Max to make a few adjustments to his plan. His

next problem was that he knew his bank account wouldn’t stretch to a visit to

New York. He ended up having to “acquire” several small objects from large

houses, which could be disposed of quickly, so he could visit the States with

enough capital to put his plan into effect. Luckily it was in the middle of the

cricket season.

When Max landed

at JFK, he didn’t bother to visit Sotheby’s or Christie’s, but instead

instructed the yellow cab to drive him to Phillips Auctioneers on East 79th

Street. He was relieved to find that, when he produced the delicate carving

stolen from the British Museum, the young assistant didn’t show a great deal of

interest in the piece.

“Are you aware

of its provenance?” asked the assistant. “No,” replied Max, “it’s been in my

family for years.” Six weeks later a sales catalog was published.

Max was

delighted to find that Lot 23 was listed as being of no known provenance, with

a high value of $300. As it was not one of the items graced with a photograph,

Max felt confident that few, if any, would take much interest in the red king,

and it would therefore be unlikely to come to the attention of either Edward or

James

Kennington

. That is, until he made them aware

of it.

A week before

the sale was due to take

place,

Max rang Phillips in

New York. He had only one question for the young assistant, who replied that

although the catalog had been available for over a month, no one had shown any

particular interest in his red king. Max feigned disappointment.

The next call

Max made was to

Kennington

Hall. He tempted his

lordship with several ifs, buts and even a maybe, which elicited an invitation

to join Lord

Kennington

for lunch at White’s.

Lord

Kennington

explained to his guest over a bowl of brown

Windsor soup that Max could not produce any papers over lunch as it was against

the club rules. Max nodded, placed the Phillips catalog under his chair, and

began an elaborate tale of how by sheer accident, while viewing the figure of a

mandarin on behalf of a client, he had come across the red king.

“I would have

missed it myself,” said Max, “if you hadn’t acquainted me with its history.”

Lord

Kennington

did not bother with pudding (bread and butter),

cheese (Cheddar) or biscuits (water), but suggested they took coffee in the

library, where you are allowed to discuss business.

Max opened the

Phillips catalog to reveal Lot 23, along with several loose photographs he had

not shown the auctioneer. When Lord

Kennington

saw

the estimate of three hundred dollars, his next question was, “Do you think

Phillips might have told my brother about the sale?”

“There is no

reason to believe so,” replied Max. “I’ve been assured by one of the assistants

working on the sale that the public have shown little interest in lot

twenty-three.”